Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 04 – April 2017ILLUSTRATION: Chris Whissen PHOTOS: shutterstock.com

Emergency department providers across the nation recognize that, every shift, patients seem older. These observations are not an illusion. Aging baby boomers will increase the number of older ED patients every year for the next few decades. Vulnerable older patients often arrive to the emergency department with multiple comorbidities and vague chief complaints that require more complex decision making and prolonged evaluation times and increase the likelihood of admissions. ED providers are concurrently pressured to increase throughput and discharge many of these patients.1 Adding the difficulty of navigating the often-complex social issues that come with caring for elder patients, the challenges increase even further. ACEP’s Geriatric Emergency Medicine Section (GEMS) developed geriatric emergency department (GED) guidelines intended to provide recommendations and guidance for optimal geriatric emergency patient care.2 These were endorsed by the ACEP Board of Directors in 2013 and also by several other national emergency medicine and geriatrics organizations.

Not all emergency departments are the same, yet optimizing geriatric emergency care across emergency departments of varying sizes and capabilities depends on prioritizing the best practices included in the ACEP GED guidelines. Best elder care depends on aligning GED practices with the resource capacity of one’s hospital and staff as well as the specific needs of one’s patients. In addition, ED leaders can use these recommendations to leverage hospital resources and the support required to care for an aging population safely and efficiently. Increasingly, hospitals are advertising “senior-friendly emergency departments,” but the process of transforming guidelines into actual health care delivery has not been standardized.3 In the fall of 2016, ACEP convened a taskforce (see Table 1) to develop a GED accreditation proposal intended to help members and hospitals provide higher-quality geriatric emergency care under increasingly challenging conditions. This proposal was approved by the Board of Directors in January 2017. Accreditation will be awarded on a three-tier platform as determined by each hospital’s level of implementation of the GED guidelines.

The ACEP GED Accreditation (GEDA) program is intended to be a transparent and minimally disruptive mechanism that assesses and publicly recognizes a hospital’s commitment to optimal geriatric emergency health care delivery. The emphasis here is on hospital responsibility because effective geriatric care requires effective interdisciplinary patient care. Success depends upon giving the emergency department needed support and hospital resources to ensure more comprehensive geriatric evaluations and timely access to follow-up care. Once a hospital commits to support credentialing an emergency department as geriatric-centered, the expectation is that the hospital will also provide and sustain the resources to effect those changes.

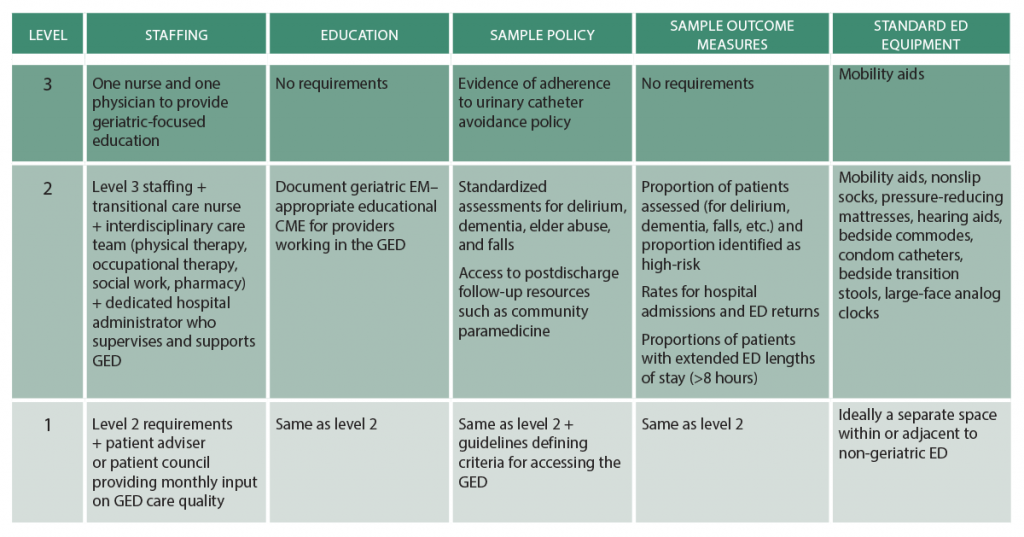

The accreditation criteria for each tier are summarized in Table 2. Level 3 GEDs represent expectations attainable by smaller hospitals, often in rural settings in which around-the-clock access to advanced imaging or labs may be limited and where staffing often includes non-physician providers. The level 3 criteria reflect these more limited resources. The level 2 criteria add expectations for demonstrable geriatric-focused staff education and guidelines as well as regular outcomes linked to specific process changes. Level 2 GEDs would be expected to achieve 75 percent adherence to at least 10 (out of 26) best practices on random chart audits of 10 total patients occurring quarterly, and they should be able to report on at least 25 percent of relevant outcome measures. Level 1 GEDs would serve as the gold standard of geriatric emergency care, demonstrating excellence by fulfilling the same criteria as Level 2 but with the addition of patient stakeholder representation, dedicated space or structures, and reporting of at least 50 percent of relevant outcome measures.

(click for larger image) Table 2: Comparisons of Established Definitions, Sepsis-3 Definitions, and SSC Guidelines

The ACEP GEDA taskforce and Board of Directors are well aware of the ever-increasing and largely unreimbursed quality and educational requirements placed on ACEP members. Being mindful of this, accreditation relies on self-reporting, has minimal associated cost, and incurs no additional CME requirements. We anticipate the accreditation process, and subsequent recognition of GED hospitals, will create a standardized and quantifiable program aligning the GED guidelines and GED accreditation with hospitals’ priorities. ACEP members at GED-accredited hospitals should therefore benefit from greater hospital resources and support that better address the needs of geriatric patients, providers, and health care systems, which ultimately will improve the care delivered to geriatric ED patients. As observed in other areas of emergency medicine, non–emergency medicine organizations could potentially dictate GED accreditation with little knowledge of the issues important to emergency physicians. Emergency physicians are setting the standard, and thus, ACEP is seizing the opportunity to determine and define our own best practices and to support the delivery of emergency care for its members.

Dr. Carpenter is associate professor of emergency medicine and director of evidence based medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Hwang is associate professor in the departments of emergency medicine and the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and research faculty at the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the James J. Peters VAMC in Bronx, New York. Dr. Biese is associate professor of emergency medicine and internal medicine, division of geriatrics, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine. is program director of the Comprehensive Advanced Life Support Program in Minneapolis. Dr. Hogan is associate professor, sections of emergency medicine and geriatric and palliative medicine, at the University of Chicago. Dr. Karounos is chief of the geriatric emergency department and director of research at St. Joseph’s Healthcare System in Paterson, New Jersey. Dr. Malone is the medical director of senior services at Aurora Health Care and serves as the American Geriatrics Society’s liaison to ACEP. Dr. Melady is an emergency physician at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. Dr. Rosen is assistant attending physician at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. Dr. Rosenberg is chairman of emergency medicine and associate professor of clinical emergency medicine at St. Joseph’s Healthcare System. Dr. Schneider is director of EM practice at ACEP. Dr. Shah is associate professor and vice chair for research and academic affairs in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison. Dr. Spiegel is assistant professor of medicine and medical director for the Mitchell Emergency Department at the University of Chicago Department of Medicine. Dr. Stern is assistant professor of medicine in emergency medicine and chief of geriatric emergency medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City.

References

- Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, et al. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff (Millwodd). 2013;32(12):2116-2121.

- Rosenberg MS, Carpenter CR, Bromley M, et al. Geriatric emergency department guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(5):e7-e25.

- Hogan TM, Olade TO, Carpenter CR. A profile of acute care in an aging America: snowball sample identification and characterization of United States geriatric emergency departments in 2013. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(3):337-346.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “ACEP Accredits Geriatric Emergency Care for Emergency Departments”