In 2021, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) published an update of their 2012 management guideline on upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB).1,2 The updated guideline included a total of 16 recommendations, of which five are relevant to emergency medicine practice:

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 07 – July 2022- ACG suggests that patients presenting to the emergency department with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) who are classified as very low risk, defined as a risk assessment score with ≤1% false negative rate for the outcome of hospital-based intervention or death (e.g., Glasgow-Blatchford score 0–1), be discharged with outpatient follow-up rather than admitted to hospital (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

- ACG suggests a restrictive policy of red blood cell transfusion with a threshold for transfusion at a hemoglobin of 7 g/dL for patients with UGIB (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).

- ACG suggests an infusion of erythromycin before endoscopy in patients with UGIB (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

- ACG could not reach a recommendation for or against pre-endoscopic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy for patients with UGIB.

- ACG suggests that patients admitted to or under observation in hospital for UGIB undergo endoscopy within 24 hours of presentation (conditional recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

Of these five recommendations there were three notable changes from the 2012 guideline.

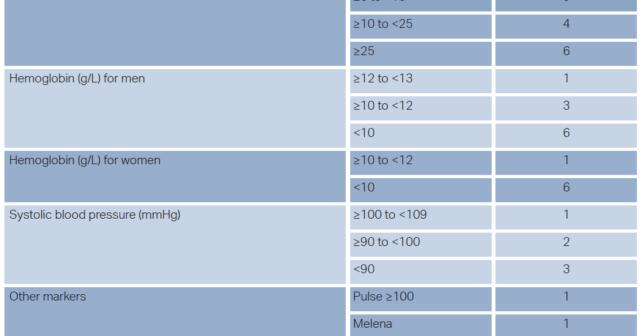

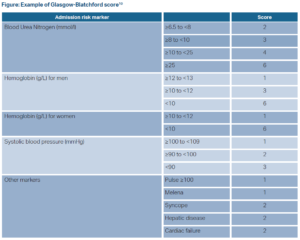

First, in risk stratifying patients, the 2021 recommendation now incorporates risk assessment scores in determining which patients are safe for discharge from the emergency department. ACG defined an appropriate risk assessment score as one with a sensitivity of ≥ 99% (i.e., a false negative rate ≤ 1%). Comparing meta-analyses, systemic reviews, and individual test accuracy studies of the Glasgow-Blatchford score, AIMS65 score, preendoscopy Rockwell score, and a published machine learning model,only the Glasgow-Blatchford and the machine learning model consistently met this standard.3 Therefore, the Glasgow-Blatchford score is the only readily available risk assessment score appropriate for use (sensitivity 0.99). Additionally, ACG expanded the number of patients the recommendation reaches suggesting that patients with a score of either 0 or 1 on the Glasgow-Blatchford score have a sufficiently small false negative rate and can be safely discharged from the emergency department (see Figure 1).

The second change revolved around the lack of recommendation for, or against, preendoscopic PPI use for patients with UGIB. The 2012 management guideline stated that preendoscopy PPI use may be considered whereas no recommendation could be reached for this 2021 guideline. This change was based on several factors. One was additional evidence available since the 2012 management guideline and subsequent meta-analysis by ACG which showed no difference in further bleeding or mortality with pre-endoscopy PPI (the benefit of PPI post-endoscopy is well known and accepted). Additionally, evolving consensus on the structure of guideline recommendations focuses on recommending specific actions. With this evolution, the ACG’s 2012 statement of “pre-endoscopic intravenous PPI may be considered” no longer fits current guideline structure. The meta-analysis conducted by ACG revealed patients with pre-endoscopic PPI had lower rates of evidence of recent hemorrhage and lower rates of hemostatic treatment during endoscopy compared to placebo. Further, indirect evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses indicate that pre-endoscopic PPI may reduce need for endoscopic treatment and may benefit a minority of patients. However, ACG was specifically looking at mortality benefit and reduced risk of rebleeding, neither of which were consistently found among the various studies included in this guideline.

This lack of recommendation for pre-endoscopic PPI does not align with other societies. Both the European Gastroenterology (2021) and an International Consensus Group (2019) recommend for the use of pre-endoscopic PPI use.4,5 However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2012) in the United Kingdom recommends against it.6

The third and final significant change revolved around the timing of endoscopy. In the 2012 guideline, ACG recommended considering endoscopy within 12 hours for patients with high-risk clinical features (e.g., tachycardia, hypotension, bloody emesis, or bloody nasogastric aspiration within the hospital). The 2021 guideline solely recommends endoscopy within 24 hours without a separate recommendation for high-risk patients. This change is based on new evidence since the 2012 guideline including a RCT of 516 patients, a nationwide cohort study of nearly 4,000 patients, and a single center cohort study of nearly 1,000 patients, all of which show no significant improvement in mortality or rebleeding with early endoscopy.7,8,9 Inthe body of the guideline, ACG did make an

anecdotal comment in favor of urgent intervention with endoscopy or interventional radiology in the subset of patients that remain in hypotensive shock after initial resuscitation.

This 2021 update provides important guidance on management of UGIB based on the best available evidence allowing emergency medicine to work in conjunction with gastroenterology to care for our patients. It should be incorporated into our standard practice as emergency physicians.

Dr. Melissa Villars is an emergency medicine resident at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.

Dr. Stephen J. Wolf is an emergency medicine physician and professor in Denver, Colorado.

References

- Laine L, Barkun AN, et. al. (2021). ACG clinical guideline: upper gastrointestinal and ulcer bleeding. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology. 116(5):899–917.

- Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology. 107(3):345–360.

- Shung DL, Au B, Taylor RA, et al. Validation of a machine learning model that outperforms clinical risk scoring systems for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:160–167.

- Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ, et al. (2021). Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline–Update 2021. Endoscopy. 53(03):300–332.

- Barkun AN, Almadi M, Kuipers EJ, et al. Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Guideline Recommendations From the International Consensus Group. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2019;171(11):805–822.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Over 16s: Management. CG141. 2012.

- Lau JYW, Yu Y, Tang RSY, et al. Timing of endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1299–308.

- Laursen SB, Leontiadis GI, Stanley AJ, et al. Relationship between timing of endoscopy and mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: A nationwide cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:936–44 e3.

- Cho SH, Lee YS, Kim YJ, et al. Outcomes and role of urgent endoscopy in high-risk patients with acute nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:370–377.

- Osman D, Djibré M, Da Silva D, et al. Management by the intensivist of gastrointestinal bleeding in adults and children. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2(1):46.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “ACEP Clinical Policies Committee reviews Gastroenterology Guideline Update”