ACEP endorsed the latest iteration of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) guidelines, totaling 67 pages with 93 statements on early management and 655 references.1,2 An important note: Guidelines should be a counselor, not a jailer. Guidelines provide a framework for direction and standardization where possible but require clinical context for individual patients. This summary includes items specifically pertinent to emergency medicine and is not intended to be all-inclusive.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 03 – March 2017Definitions

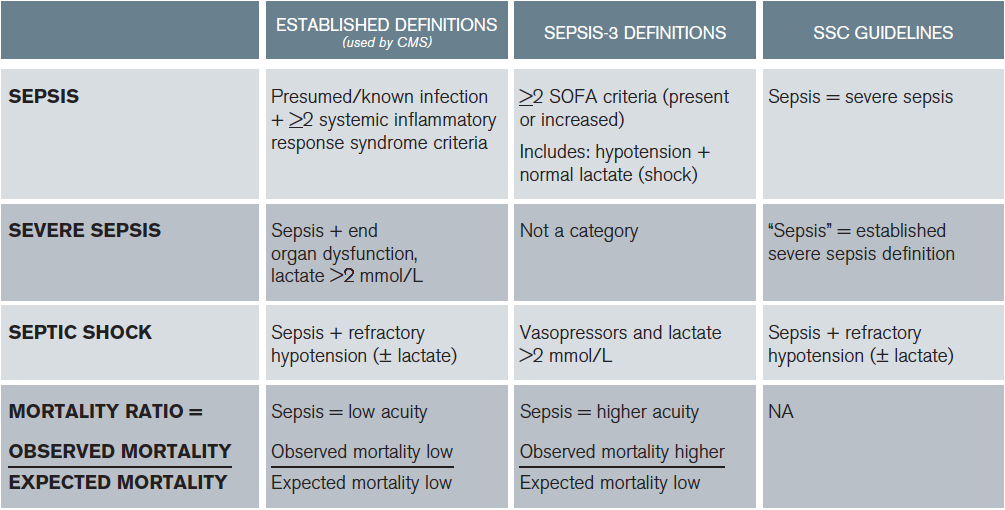

All the data informing guideline development were based on the established definitions, not Sepsis-3. The Sepsis-3 and established definitions were modified for the purpose of guideline application.3 In the 2016 SSC guidelines, sepsis equates to the established definitions of severe sepsis (infection + organ dysfunction, including hyperlactemia) and septic shock (hypotension ± lactate). The Quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) did not inform any part of the guidelines. ACEP and other organizations did not support or endorse the Sepsis-3 definitions due to patient safety concerns.4,5 The SSC guidelines acknowledged that:

- There is insufficient data to apply the Sepsis-3 definitions to the guidelines.

- Lactate is important and part of the established definition of severe sepsis (or sepsis in the guidelines). Additionally, the guidelines highlight the importance of lactate normalization. Both early monitoring and early management of hyperlactemia are key components of emergent resuscitation and patient care principles important in ACEP’s decision to support the guidelines when it did not support the Sepsis-3 definitions.

Consistent with the law of unintended consequences, even when compatible care is provided, clinicians implementing Sepsis-3 definitions may appear to provide worse care than those using established definitions on national quality metrics (see Table 1). So now there are three definitions: the established definitions, the SSC definitions that are based on the established definitions, and the Sepsis-3 definitions (see Table 1). What a mess. Which ones do we use? I suggest that we use the established definitions for care.

(click for larger image)

Table 1: Comparisons of Established Definitions, Sepsis-3 Definitions, and SSC Guidelines

Mortality ratio, national quality metrics based on established definitions (expected mortality). When clinicians apply a low-acuity diagnosis (sepsis) to a higher-acuity patient (Sepsis-3 definition of sepsis), the observed mortality will be higher than expected. Results in similar care appearing worse based on different definitions applied to the same patients. Note: CMS recognizes normotension + lactate ≥ 4 as septic shock

Perhaps future prospective evaluation will support the use of Sepsis-3 and qSOFA. However, that should be played out in further academic work and not via national payment metrics.

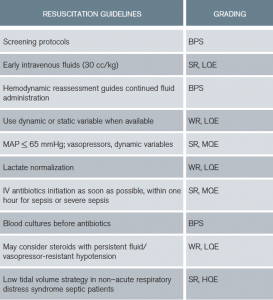

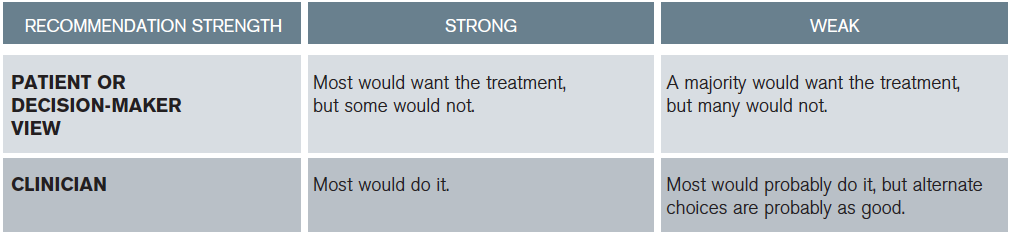

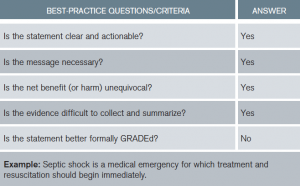

New to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology is the replacement of numbers and letters with “strong or weak” recommendations followed by quality of evidence (see Tables 2 and 3). Best-practice statements (BPSs) are recommendations to which the committee felt GRADE criteria could not be applied but pass the “common sense” test (see Table 4).

ED-Specific Recommendations and Changes

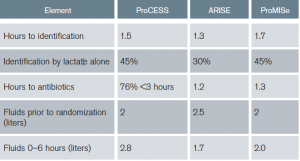

Early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) is no longer recommended. Specifically, given no benefit in the general population of septic patients, central venous pressure (CVP), hematocrit, and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) goals are not encouraged. Additionally, given no demonstrated harm, combined with no evaluation of specific subgroups, there is no recommendation against using some of the goals if the clinician feels indications exist. The original EGDT trial was pivotal in changing the mindset of clinicians around the world regarding sepsis time sensitivity and highlighting emergency physicians as the resuscitation experts.6 However, application over a decade later through three international randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and subsequent meta-analyses resulted in no difference between strict EGDT and usual care, with this important caveat.7–9 All three trials had protocols providing early identification (1–2 hours from triage), early antibiotics (1–3 hours), early IV fluid (2.5–3 liters before starting EGDT), and early lactate measurement (30%–45% identified by lactate alone: normotension + lactate ≥ 4) (see Table 5). Institutions not having these protocols in place may not achieve equivalent findings.

(click for larger image)

Table 5: Summary of ProCESS, ARISE, and ProMISe: Components of Usual Care Resuscitation

Fluid Resuscitation

The guidelines recommend 30 mL/kg of fluid within the first three hours (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence). Denoting “low quality of evidence” demonstrates acknowledgement of limited data supporting this recommendation. This was a source of significant debate among committee members with strong opinions regarding the data on both sides. Data supporting the potential to do harm with excessive fluid administration were compared to data supporting potential harm regarding insufficient volume administration. Ultimately, it passed because, before randomization, ProCESS and ARISE used volumes consistent with 30 cc/kg and ProMISe used two liters in its usual care patient populations (see Table 5). Additionally, other observational evidence was supportive.10,11 However, growing information regarding diastolic dysfunction, right ventricular dysfunction, and obesity may require reconsideration of fluid volume in the next iteration.12,13 In most 70 kg patients, two liters may be a reasonable start. However, limited data exist in 300 kg patients; nine liters is potentially too aggressive.

Subsequent Hemodynamic Assessment

To summarize, after the initial fluid challenge, most physicians would reevaluate complex patients prior to administering more fluid (see Table 6). When available, use of dynamic over static variables for fluid responsiveness is advised.14 Finally, using CVP alone to determine fluid responsiveness is not justified. Emergency medicine in the United States is a leader in the use of ultrasound and other noninvasive strategies to direct emergent resuscitation. However, this is not consistent globally, where many clinicians struggle to provide the best care they can in resource-limited areas.

(click for larger image)

Table 6: Resuscitation Guidelines Summary

BPS = best-practice statement; SR = strong recommendation; WR = weak recommendation; HQE = high quality of evidence; MQE = moderate quality of evidence; LQE = low quality of evidence

Lactate

The guidelines suggest guiding resuscitation to normalize lactate. Serum lactate is not a direct measure of tissue perfusion. There are patient populations in which lactate may not represent physiologic decline, for example, those with decreased clearance (liver dysfunction) and type B lactic acidosis, such as with beta-adrenergic stimulation from endogenous or exogenous catecholamine (eg, epinephrine). In limited patient populations demonstrating consistent physiologic stability, persistent therapies focused on lactate reduction may not be beneficial. However, this is a diagnosis of exclusion to be evaluated within specific clinical context and should not be initially applied to patients presenting in distress. The data overwhelmingly support an association between hyperlactemia and mortality. Increased mortality is reported in patients with or without hypotension, and some data support a dose-response curve.15–18 Any lactate reduction is associated with sequential survival benefit in compromised patients and is the initial step toward the goal of normalization.

Antibiotics

The guidelines recommend IV antibiotic administration as soon as possible after recognition and within one hour for sepsis and septic shock (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence). This recommendation was based upon data demonstrating increased mortality for every hour of delay in antibiotic administration for infected patients with organ dysfunction and/or shock.19,20 These are patients in distress, most especially those in septic shock. However, a meta-analysis reported no benefit of rapid antibiotic administration. Although several poor-quality studies were included, the meta-analysis called into question the one-hour target. Ultimately, the recommendation of antibiotics within one hour for both sepsis and septic shock was considered “a reasonable minimal target” based upon the largest highest-quality studies in the meta-analysis. It is currently unclear, especially in sepsis compared to septic shock, if antibiotic administration within one hour is better than within three. Current Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance is to administer antibiotics as soon as possible and within three hours of sepsis or septic shock diagnosis.

EGDT is no longer recommended. Specifically, given no benefit in the general population of septic patients, CVP, hematocrit, and ScvO2 goals are not encouraged.

Although the guideline-drafting process has improved, it still is subject to the weakness of human interpretation and available data at the time of analysis. Guidelines cannot replace clinical acumen or negate our responsibility to consider unique patient variables or physiology. Emergency medicine should continue to contribute innovation to the areas of resuscitation, including:

- The screening of infected patients for the potential of decline

- Fluid volume and time endpoints, including methods of fluid-responsiveness assessment

- Use of biomarkers, including lactate

- The impact of time to antibiotics with respect to severity of illness

Dr. Osborn is professor in the department of surgery and division of emergency medicine at Barnes-Jewish Hospital at Washington University in St. Louis.

Dr. Osborn is professor in the department of surgery and division of emergency medicine at Barnes-Jewish Hospital at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304-377.

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486-552.

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810.

- Simpson SQ. New sepsis criteria: a change we should not make. Chest. 2016;149(5):1117-1118.

- Machado FR, Salomão R, Pontes de Azevedo LC, et al. Why LASI did not endorse the new definitions of sepsis published today in JAMA. Latin American Institute of Sepsis website. Accessed Feb. 21, 2017.

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377.

- Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1301-1311.

- ProCESS Investigators, Yealy DM, Kellum JA, et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1683-1693.

- Peake SL, Bailey M, Bellomo R, et al. Australasian resuscitation of sepsis evaluation (ARISE): a multi-centre, prospective, inception cohort study. Resuscitation. 2009;80(7):811-818.

- Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(1):3-12.

- Cecconi M, De Backer D, Antonelli M, et al. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(12):1795-1815.

- Sankar J, Das RR, Jain A, et al. Prevalence and outcome of diastolic dysfunction in children with fluid refractory septic shock—a prospective observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(9):e370-e378.

- Matyal R, Skubas NJ, Shernan SK, et al. Perioperative assessment of diastolic dysfunction. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(3):449-472.

- Cecconi M, Hofer C, Teboul JL, et al. Fluid challenges in intensive care: the FENICE study: a global inception cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(9):1529-1537.

- Puskarich MA, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI, et al. Whole blood lactate kinetics in patients undergoing quantitative resuscitation for severe sepsis and septic shock. Chest. 2013;143(6):1548-1553.

- Casserly B, Phillips GS, Schorr C, et al. Lactate measurements in sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion: results from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign database. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):567-573.

- Puskarich MA, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI, et al. Outcomes of patients undergoing early sepsis resuscitation for cryptic shock compared with overt shock. Resuscitation. 2011;82(10):1289-1293.

- Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D, et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(5):524-528.

- Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589-1596.

- Ferrer R, Martin-Loeches I, Phillips G, et al. Empiric antibiotic treatment reduces mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock from the first hour: results from a guideline-based performance improvement program. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1749-1755.

5 Responses to “ACEP Endorses Latest Surviving Sepsis Campaign Recommendations”

March 31, 2017

John ReevesWell done review! Thank you so much – very helpful

April 2, 2017

Munish GoyalGreat work, Tiffany. This very nicely summarizes the different definitions, some of the confusion, and a logical path forward.

One thing caught my eye in table 1 — the established definition (CMS) of severe sepsis includes an elevated lactate (> 2.1 at my shop), not lactate > 4.

April 28, 2017

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you for pointing this out, Dr. Goyal. The table has been corrected.

March 18, 2018

Rushdi AlulHello Dr. Osborn,

I am an internist working in the Chicago area and I would like to commend you for writing such an excellent article. I am contacting you in regard to a comment in your article, specifically your recommendation to use the established definitions for sepsis used by CMS. My confusion is the following. I will see on a regular basis young adults, for example, a 21 year old male complaining of fever and sore throat and noted to have a heart rate >90 bpm. After examination if appropriate, I will perform a rapid strep test. Assuming the strep test is positive I will tell him he has strep throat and treat him accordingly. However he meets the CMS guideline for sepsis, is his correct diagnosis strep throat with sepsis?? I am reluctant to use sepsis in this scenario since I am accustomed to associating sepsis with patients who display evidence of clinical or hemodynamic instability (requiring resuscitative intervention) which this young man does not have nor need. Any clarification or insight you can provide would be greatly appreciated!

March 20, 2018

Rushdi AlulDr. Osborn,

I would like to commend you for writing such an excellent article. I am contacting you in regard to a comment in your article, specifically your recommendation to use the established definitions for sepsis used by CMS. My confusion is the following. I will see on a regular basis young adults, for example, a 21 year old male complaining of fever and sore throat and noted to have a heart rate >90 bpm. After examination if appropriate, I will perform a rapid strep test. Assuming the strep test is positive I will tell him he has strep throat and treat him accordingly. However he meets the CMS guideline for sepsis, is his correct diagnosis strep throat with sepsis?? I am reluctant to use sepsis in this scenario since I am accustomed to associating sepsis with patients who display evidence of clinical or hemodynamic instability (requiring resuscitative intervention) which this young man does not have nor need. Any clarification or insight you can provide would be greatly appreciated!