While pericarditis is an unusual diagnosis, with an annual incidence of 27.7 per 100,000 persons, the recurrence rate of almost 30 percent is surprisingly high.1 Many of the patients diagnosed with acute pericarditis in the emergency department (ED) will relapse and some will develop debilitating, chronic, constrictive pericarditis. The mortality rate of 1.1 percent in developed countries is also significant.1 The good news is that timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment options have been shown to decrease recurrence rates and help prevent chronic complications.2 However, considering that the clinical presentation, electrocardiogram (ECG), and laboratory findings may be confused with more deadly causes of chest pain such as myocardial infarction (MI), aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism, pericarditis should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion in the ED. Here are some practical tips on how to distinguish pericarditis from more deadly causes of chest pain and a review of the literature on time-sensitive treatment that reduces recurrence and complications of pericarditis.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 07 – July 2022What Sets Pericarditis Apart?

The clinical presentation of pericarditis overlaps with MI, pulmonary embolism, and aortic dissection, but usually includes several features that can help distinguish it from these more deadly causes of chest pain. Persistent chest pain for weeks is not typical for these other deadly diagnoses and should raise suspicion for pericarditis. Pericarditis can occur at any age, and these other deadly diseases can occur in young patients, however, young, otherwise healthy patients with chest pain and no risk factors for MI, aortic dissection, or pulmonary embolism should raise the suspicion for pericarditis. A respiratory or gastroenterological viral prodrome that may include malaise, myalgias, and low-grade fever is common in patients with acute pericarditis and less common in patients with MI.

Chest pain in patients with pericarditis is typically central, pleuritic, sharp, worse on lying supine, and better on sitting up and leaning forward. The pleuritic chest pain of pericarditis is usually central and diffuse as opposed to pulmonary embolism and pneumothorax where the pain is usually lateralized and focal. Sometimes the pain radiates to the back, neck, or shoulder, as in patients with MI. Radiation to the trapezius ridge is common. A cardiac friction rub—while traditionally thought of as highly specific for pericarditis—may be falsely identified in hirsute patients when chest hair rubs against the stethoscope with rise and fall of the chest during auscultation. Despite these distinguishing features, however, there is no group of clinical features with sufficient specificity to rule in pericarditis with certainty, underlining the concept that it should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion. It is important to realize, as well, that pericarditis may occur concurrently with aortic dissection and MI.

On inspection of the guideline-based diagnostic criteria of pericarditis listed below, one can plainly realize that each of the criteria can occur in patients with other more deadly diagnoses.3 For example, pleuritic chest pain is common in pulmonary embolism. As explained above, pericardial friction rub can be misinterpreted as present in hirsute patients. New widespread ST elevation can occur in MI. New or worsening pericardial effusion can occur with aortic dissection.

The diagnosis of pericarditis requires two out of four of the following criteria:3

- Pericarditis chest pain—typically sharp, pleuritic, positional

(greater than 80–90 percent of cases)

- Pericardial rub on auscultation (less than one third of cases)

- New widespread ST elevation or PR depression on ECG (up to 60 percent of cases)

- New or worsening pericardial effusion (up to 60 percent of cases)

Additional supporting findings:

- Elevation of markers of inflammation (e.g., C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), white blood cell (WBC) count)

- Evidence of pericardial inflammation by imaging technique (contrast computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance)

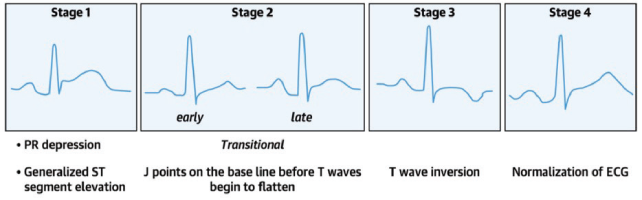

The ECG findings of pericarditis, in particular, may be confused with early repolarization and acute MI. It is important to understand that the ECG findings in patients with pericarditis evolve through four stages (see image) and that patients may present during any of the stages.4 The classic diffuse ST elevation/PR depression (Stage 1) is found in only 60 percent of patients. The evolution of the four changes over time is highly variable and some patients may skip directly from Stage 1 to Stage 4 (normalization). In addition, uremic pericarditis typically does not cause significant inflammation of the epicardium, hence the ECG and the inflammatory markers are more likely to be normal in this subgroup of patients.

Here is a list of ECG features that may help to distinguish pericarditis from MI and early repolarization.5–8 Nonetheless, all of these findings can be seen in patients with cardiac ischemia, underlining again the importance of approaching pericarditis as a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Widespread/diffuse PR depression and/or ST elevation (STE)

- J-point in pericarditis is usually sharper compared to a more blurred J point in MI

- STEs are more commonly convex shaped in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), while concave upwards ST elevations are more typical of pericarditis

- If STE or PR depression is present, there is typically a preservation of the normal upright T-waves in pericarditis (note however, that Stage 3 is defined by T-wave inversions)

- STE is rarely >5mm in pericarditis

- ST depressions in V1 and aVR favor pericarditis

- aVL ST segment is typically elevated in pericarditis while aVL ST depression is highly specific for inferior MI

- STE II>STE III favors pericarditis while STE III>STE II is highly suspicious for inferior STEMI

- Spodick’s sign (80 percent of patients with acute pericarditis and five percent of MI) is characterized by down-sloping from the T wave to the QRS segments with the terminal PR segment depressed; this is best seen in lead II and the lateral precordial leads.

Distinguishing ECG findings of pericarditis versus early repolarization:

- PR deviation strongly favors pericarditis

- Evolution of ST and T changes strongly favors pericarditis

- STE: T-wave amplitude ratio >0.25 has a 100 percent positive predictive value and negative predictive value for pericarditis

- Pericarditis STE is typically more evenly distributed and sometimes more prominent in the inferior leads, whereas early repolarization STE is more prominent in anterior leads.

Troponin, in one study, was elevated in one third of cases of pericarditis, and is often associated with STE on ECG and pericardial effusion.9 Inflammatory markers (WBC, ESR, and CRP) are elevated in up to 80 percent of cases, but these markers are not sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of acute pericarditis.10 Patients with elevated CRP are at higher risk for recurrence and should be treated in a timely and aggressive manner.11

Prevention of recurrence is perhaps the most important aspect of ED treatment of acute uncomplicated pericarditis because recurrence leads to long-term morbidity. Colchicine is the mainstay of ED treatment of acute pericarditis and has been shown in multiple randomized control trials to decrease recurrence and long-term morbidity.12–15 A common cause of recurrent pericarditis is inadequate treatment of the first episode. Up to 30 percent of patients with idiopathic acute pericarditis who are not treated with colchicine will develop either recurrent or incessant disease. Outpatient management of presumed viral/idiopathic uncomplicated pericarditis should include the following:

- Restrict strenuous physical activity (as exercise may trigger recurrence of symptoms)

- Ibuprofen 600–800 mg three times daily or indomethacin 50 mg three times daily

- Colchicine 0.6 mg daily for <70 kg, twice daily for ≥70 kg

- Proton pump inhibitors for those at high risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Duration of uncomplicated pericarditis treatment is usually one to two weeks and is based on resolution of symptoms and normalization of CRP, typically followed by a taper of medications. Corticosteroids should be considered only as a second-line option after nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients with absolute contraindications to or failure of NSAIDS because of the risk of chronicity of disease and drug dependence with steroids.

Next time you are faced with a patient with chest pain in the ED, first, rule out other more deadly causes of chest pain first (understanding that there are no clinical features specific to pericarditis), carefully scrutinize the ECG (realizing that no finding is 100 percent specific for pericarditis), and if you arrive at a diagnosis of uncomplicated viral or idiopathic acute pericarditis, be sure to start the patient on colchicine and NSAIDs and also ensure tight follow-up to monitor the clinical course and consideration of serial CRP measurements.

A special thanks to Drs Jess McLaren, Walter Himmel and Paul Dorian for their expertise on the EM Cases podcast from which this article was inspired.

Dr. Helman (@EMCases) is an emergency physician at North York General Hospital in Toronto. He is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Division of Emergency Medicine and the education innovation lead at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. He is the founder and host of Emergency Medicine Cases podcast.

References

- Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis. Lancet. 2004;363 (9410):717–27.

- Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of acute and recurrent pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(1):76-92.

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. European Heart Journal. 2015;36(42):2921-2964.

- Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of acute and recurrent pericarditis: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(1):76-92.

- McLaren J. ECG cases 27 pericarditis – diagnosis of exclusion. Emergency Medicine Cases website. Published online November 2021. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/ecg-cases-pericarditis-diagnosis-exclusion/

- Witting MD, Hu KM, Westreich AA, et al. Evaluation of Spodick’s sign and other electrocardiographic findings as indicators of STEMI and pericarditis. J Emerg Med. 2020;58(4):562-569.

- Bischof JE, Worrall C, Thompson P, et al. ST depression in lead aVL differentiates inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction from pericarditis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:149-154.

- Bhardwaj R, Berzingi C, Miller C, et al. Differential diagnosis of acute pericarditis from normal variant early repolarization and left ventricular hypertrophy with early repolarization: an electrocardiographic study. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345(1): 28-32.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E, et al. Cardiac troponin i in acute pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(12):2144-2148.

- Ismail TF. Acute pericarditis: Update on diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2020;20(1):48-51.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115(21):2739-2744.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Imazio M, et al. International collaborative systematic review of controlled clinical trials on pharmacologic treatments for acute pericarditis and its recurrences. Am Heart J. 2010;160(4):662-670.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cemin R, et al. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1522-1528.

- Alabed S, Cabello JB, Irving GJ, et al. Colchicine for pericarditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 28;(8) ):CD010652.

No Responses to “Acute Pericarditis: A Diagnosis of Exclusion”