New waves and challenges of COVID-19 keep coming. Emergency physicians keep managing the front lines, caring for patients with increasing severity of illness and stacked in hallway beds in the emergency department.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 02 – February 2022The performance of emergency departments in 2020 has been summarized by the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) in its annual survey report. One of the operational changes that occurred in the pandemic year was a significant increase in patient transfers from emergency departments. This trend is no doubt accelerating in 2022.

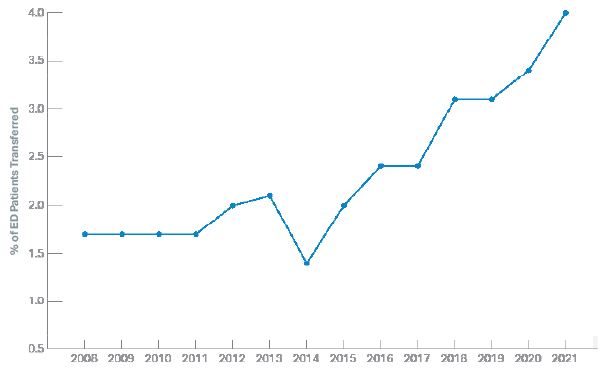

The average transfer rate in 2019 for all emergency departments was about 3.1 percent. The data for 2020 showed a transfer rate of 3.4 percent, with the ongoing transfer rate higher in small-volume emergency departments at 5.6 percent. Transfer rates were up across all types of departments. More important, the transfer rate of 3.4 percent was twice that of the survey done in 2011. Table 1 displays the trends in ED transfer rates over the last 13 years.

How Many Patient Encounters Does That Reflect?

The ED volume in the United States in 2019 was around 160 million patients. At the 3.1 percent transfer rate, that was almost 5 million patients being transferred in a year, or almost 14,000 patients a day. That is a lot of patient movement, with each transfer requiring significant coordination work and compliance programs related to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) requirements. These data do not include freestanding emergency departments, which have patients who can place additional burdens on the transfer resources of hospitals and hospital systems.

This only represents ED transfers; some hospitals also must transfer patients out of inpatient units when patient needs are identified that cannot be managed in the first hospital.

Table 1. Trends in Transfers of ED Patients

Which Patients Are Being Transferred?

The annual study of ED visits by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in its National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey characterizes ED visits by disposition. One of the disposition types is patients being transferred to psychiatric hospitals. From 2011 to 2019, the CDC reports that about one-third of patient transfers were to psychiatric facilities for mental health treatments. That is true for the last set of data tables published for ED visits in 2018.1 Mental health transfers represent one of the greatest areas of specialized care, which hospitals appear unprepared to handle. And this was prior to COVID, which makes these types of transfers even more difficult.

What Factors May Be Contributing to ED Transfers?

ED transfer rates vary dramatically by cohorts, as seen in Table 2. Transfer rates in small-volume emergency departments are at least five times higher than those of high-volume ones.

The results of the survey indicate that fewer hospitals in rural communities have the resources to keep complex patients. This included COVID patients in 2020. Rural hospitals have been closing service lines and been unsuccessful in recruiting physicians willing to care for complex patients. Rural facilities also have limited financial resources to care for high-cost patients.

Table 2: ED Patients Transferred, by Cohort of EDs, in 2020

| Emergency Department Cohort | % of ED Patients Transferred |

|---|---|

| All EDs | 3.4 |

| Adult EDs | 1.6 |

| Pediatric EDs | 2.5 |

| Over 80K volume | 0.9 |

| 60–80K | 1.6 |

| 40–60K | 2.1 |

| 20–40K | 2.9 |

| Under 20K volume | 5.6 |

Moving Toward Solutions to Flow of Admitted and Transfer Patients

The role of emergency physicians and hospital leaders has dramatically escalated with the surges and medical system challenges produced by the COVID pandemic. The trends suggest emergency departments will see higher-acuity patients and more patients with complex medical needs.2

The emergency department is the portal into the hospital for critical patients who will either be admitted or transferred. Patients admitted from the emergency department account for about 67 percent of overall hospital admissions in addition to patients who will be transferred for admission to other hospitals. Any patient who requires boarding constitutes a challenge to ED operations, one that occurrs now for both admitted and transferred patients.

Because about a third of transfers relate to patients with mental health needs, the emergency department would benefit from community practices that feature the use of sites other than the emergency department for the management of persons with mental health and substance abuse issues. There are communities looking to implement mental health care sites and sobering centers as well as mechanisms that allow police and EMS to refer patients directly to those sites rather than to an emergency department.3–6 The ability to process these individuals primarily to a site of quality mental health and substance abuse care is a positive and preserves the focus of ED care on medical and trauma patients.

Patient transfers are not infrequent and are resource-intensive for emergency physicians and nurses. Hospital and ED leaders must ensure that emergency physicians have easy-to-implement “patient transfer packs” that conform to EMTALA guidelines. Those processes allow the many steps to successful patient transfer to occur in an efficient matter, without wasting the time of the ED physician, nurse, or clerk trying to complete the process.

Many hospital systems have developed patient flow centers (or transfer centers), which had an important role even pre-pandemic in efficiently moving patients to the best site of care within the system. In response to pandemic surges, some states have developed dedicated hospital coordinating centers to improve the flow of patients outside of established hospital systems in an attempt to match patient needs with resources.7,8 These centers certainly have a future role.

The rapid increase in ED patient transfers is a marker of the growing centralization of certain high-intensity clinical services and illustrates the need for a very effective system for organizing the movement of patients to those needed services. Perhaps it means that certain critical services need to be decentralized and delivered in more hospitals.

There is clearly a mismatch of services when millions of patients with mental health needs are processed in emergency departments and then packaged for transport to a definitive site of care.

Emergency physician leaders must appreciate the monumental challenges in acute care delivery that are occurring in the pandemic years and work with hospital leaders to serve a changing emergency population in the near future. Telehealth may have an important role in this regard.

The need to serve ED patients who must be transferred for definitive care is yet another important management priority

References

- Cairns C, Kang K, Santo L. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2018 emergency department summary tables. CDC website. Accessed on Jan. 19, 2022.

- Augustine JJ. Pre-COVID ED trends suggest more challenges lie ahead. ACEP Now. 2020;39(11):10.

- Russell T, Doom A. Dallas works to avoid sending people in crisis to emergency rooms or jails. Pew website. Accessed on Jan. 19, 2022

- Leseman M. Mental health first responders coming to Anchorage in 2021. Alaska’s News Source website. Accessed on Jan. 19, 2022.

- Waters R. Enlisting mental health workers, not cops, in mobile crisis response. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(6):864-869.

- Whelan R. Americans seek urgent mental-health support as Covid-19 crisis ebbs. Wall Street Journal. June 27, 2021.

- Galvagno Jr SM, Naumann A, Delbridge TR, et al. The role of a statewide critical care coordination center in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic—and beyond. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(11):e0568.

- Georgia Coordinating Center. Georgia Department of Public Health website. Accessed on Jan. 19, 2022.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Another COVID Casualty: the Emergency Department Transfer Process”