Medicine has its dogma, but sometimes it’s wrong and, rarely, it’s challenged and disproved. Recall, “Pain meds interfere with evaluation of abdominal pain”?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 10 – October 2016So bring on the dogma, “To cut is to cure,” for management of the skin abscess, epidemic in emergency departments since the emergence of a new strain of staph, community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

It’s not the cutting that’s at issue, rather the tenet that antibiotics don’t lead to any better outcomes after adequate drainage, just more cost and side effects. That’s what’s been taught and was supported by small studies, including two randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) of approximately 200 total participants each done during the MRSA era.

In your practice, is drainage all you do, or does that depend on your last case of epidural abscess or Stevens-Johnson syndrome? On March 3, 2016, this dogma had its day. In The New England Journal of Medicine, my colleagues and I described the first large RCT comparing trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) to placebo.1 This National Institutes of Health–funded double-blind study involved more than 1,200 ED patients who had abscesses evaluated by bedside ultrasound, received standardized drainage, and were followed for eight weeks. Participants were discharged and treated with twice the usual TMP/SMX dose, two double-strength tablets BID for seven days, now ED-slanged as “Octa-Bactrim” for eight single-strength tabs per day. Almost all patients were adults, 11 percent had diabetes, and 18 percent gave a history of fever, but a measured temp >38oC was rare. Most abscesses were small, median diameter 2.5 cm (minimum 2 cm, 75 percent were <3.5 cm), with median 7 cm erythema. In 20 percent, the abscess area was >75 cm2.

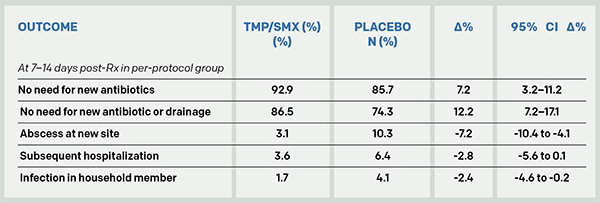

To our surprise, we found that TMP/SMX led to significantly better outcomes and only slightly more, mostly mild, gastrointestinal side effects and no serious reactions. The number and types of the improved outcomes were notable (see Table 1). At seven to 14 days, significantly fewer TMP/SMX-treated participants had clinical failure requiring a new antibiotic or another drainage procedure. There was a trend toward half the rate of subsequent admits, fewer recurrences, and even fewer infections in household members. Through eight weeks, new abscesses developed in 10.1 percent of the TMP/SMX group compared to 19.1 percent of the placebo group. These findings were for the per-protocol group, the 85 percent who complied and followed-up, but also held up in the intention-to-treat population. This evidence supports routine antibiotic use.

(click for larger image)

Table 1: Outcome of Patients with a Drained Skin Abscess Randomized to TMP/SMX or Placebo

So do we now abandon, “Just say ‘no’ to antibiotics for abscesses,” and risk promoting bacterial resistance Armageddon? There’s another perspective to these results. Most patients recover with drainage alone, 85.7 percent not needing a new antibiotic and 74.3 percent not needing either a new antibiotic or more drainage. Further, the placebo group was found to be at no increased risk of subsequent rare invasive infections.

I asked an emergency medicine antibiotic stewardship expert, Larissa May, MD, MSPH, MSHS, at the University of California, Davis. She replied, “I would argue that these results cannot be generalized to truly uncomplicated abscesses as a substantial minority of participants fell into the moderately ill category (diabetes, systemic signs of infection, and abscesses >75 cm2). I am more likely to treat patients who suffer from repeated infections. In addition, even if the study reinforces the current practice of prescribing antibiotics to most patients with uncomplicated abscesses, there is opportunity for decreasing duration of antibiotic use. The authors chose seven to 10 days, which is not necessary.”

Emergency physicians are routinely second-guessed when complications occur, so I asked an infectious diseases expert, Brad Spellberg, MD, at Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center, who advises the US Food and Drug Administration on antibiotic trials, about his take. He replied, “I cannot understand people’s fixation on not giving antibiotics to people we know have bacterial infections, but they seem to be perfectly at ease blasting people with viral bronchitis, sinusitis, otitis, etc. with pseudomonally active therapy, typically with vanco. … Patients with abscesses need to be treated. … Your data have frankly made it below the standard of care not to do so.”

Brad, we caught the dig about our vosyn abuse. Ouch. We’ll keep working on that.

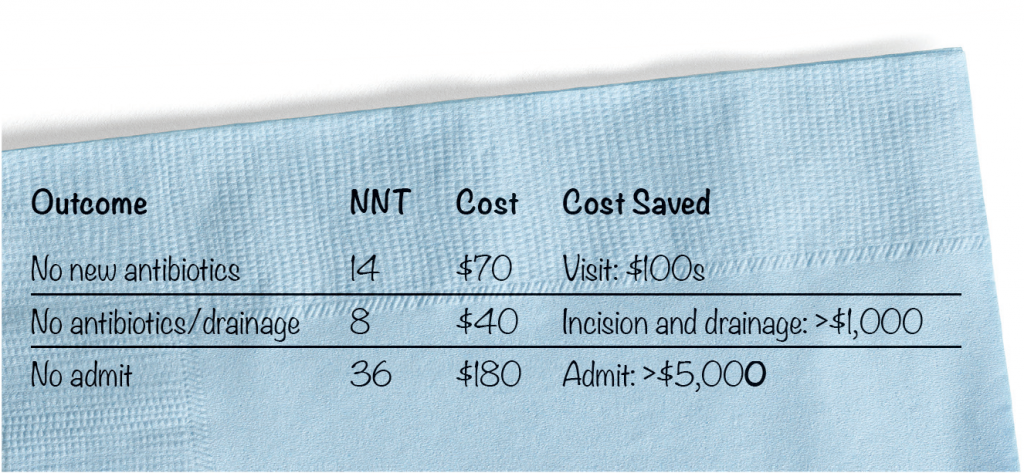

A seven-day course of TMP/SMX costs about $5 on GoodRx.com. Here’s a back-of-the-napkin cost analysis (see Figure 1).

(click for larger image)

Figure 1. Back of Dave’s Napkin: Number Needed to Treat (NNT) and Cost/Savings to Prevent One Failed Case

With an antibiotic that is so cheap, routine use is cost-saving, even with a small outcome benefit considering the savings in avoiding a return visit and especially an extra drainage procedure or hospitalization.

“I cannot understand people’s fixation on not giving antibiotics to people we know have bacterial infections, but they seem to be perfectly at ease blasting people with viral bronchitis, sinusitis, otitis, etc. with pseudomonally active therapy, typically with vanco. … Patients with abscesses need to be treated. … Your data have frankly made it below the standard of care not to do so.” —Brad Spellberg, MD, at Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center

Jerry Hoffman, MD, perhaps emergency medicine’s toughest literature critic, concluded, “I was quite surprised by the results … and actually wished they’d been different. But this is very good evidence, and certainly the best we have, of a small but real benefit. So it strongly suggests that a few days of antibiotics is worth it.” This new evidence at least opens the door to a discussion with your patient.

Some have suggested untested strategies like giving a later-dated just-in-case prescription, not treating smaller abscesses, and treating for fewer days. We’re conducting subgroup analyses to test abscess mythology, like antibiotics are only effective for those with bigger lesions, more erythema, fever, or comorbidities. One double-strength BID could work just as well. There is another RCT that used this dose (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT00730028), and we’ll see if that study validates our findings.

In the meantime, you can decide if it’s time to discard abscess treatment dogma and if, with this new evidence, matters have now come to a head!

Dr. Talan is professor of medicine in residence (emeritus) at David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and chairman emeritus of the department of emergency medicine and faculty in the division of infectious diseases at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Reference

- Talan DA, Mower WR, Krishnadasan A, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus placebo for uncomplicated skin abscess. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):823-832.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Antibiotic Therapy for Abscesses Medical Dogma Challenged by Evidence-Based Research, Outcomes”