Prevent overuse of Foleys in the ED by knowing which patients do—and don’t—need them and working with the care team to follow best practices

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014You’re about to evaluate a new patient when a veteran nurse says, “Hey Doc, I saw the orders for the delirious patient in room 8. I’m going to place a Foley for a urine sample, since she’s already wet the bed twice.” Your mind is already on the next patient, so you utter, “Sure,” without further thought.

Indwelling urinary catheters, a.k.a. Foleys, can be critical in managing urinary obstruction, fluid balance, and traumatic conditions. Yet potential harms and costs include the discomfort of insertion and the costs of the Foley equipment and placement, as well as the rare but serious complication of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs). CAUTI is the most common hospital-acquired infection, accounting for between 95,000 to 387,000 annual, preventable infections in the United States. Assuming Foleys stay in for roughly two days and the average infection rate for medical/surgical wards is 1.5 per 1,000 catheter days, one in 333 Foleys will cause an infection.

How often do we place Foleys in the emergency department (ED)?

We place Foleys for medical reasons, patient and staff convenience, and out of habit. Catheter insertion is one of the most frequent procedures in US EDs. A national survey estimated that 2 percent of ED patients in 2010 had a Foley placed.1 Single center studies show that up to 23 percent of ED patients who are admitted have a Foley placed in the ED, and the percentage is even higher (30–36 percent) among elderly patients.2-4 Yet, between a third and a half of Foleys placed in hospitalized ED patients lack documented physician orders, and one study found that up to half are avoidable.2,4

Assuming Foleys stay in for roughly two days and the average infection rate for medical/surgical wards is 1.5 per 1,000 catheter days, one in 333 Foleys will cause an infection.

Who needs a Foley catheter?

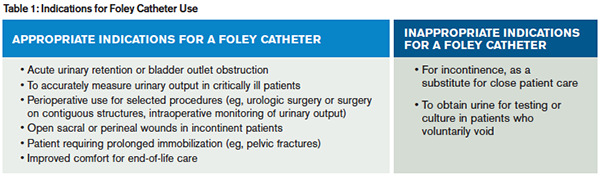

In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a “Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections,” including indications for Foley use (see Table 1).5 While not developed specifically for the ED and largely based on expert opinion, they are a useful starting point.

Based on CDC Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee guidelines.5

In what patient scenarios can Foley placement be avoided?

- Patients with congestive heart failure exacerbations: Historically, Foley placement helped measure “ins and outs.” However, non-critical patients who make urine can have their output measured from a urinal or commode.

- Incontinence: A frequent reason for placing a Foley that should be avoided is solely for the convenience of the patient or staff.

- Difficulty obtaining a urine sample: Try a straight cath instead of an indwelling Foley.

- Measurement of post-void residual bladder volume: Bedside ultrasound or a bladder scanner is fast, accurate, and non-invasive.

- Trauma patients: While traditional trauma training dictated Foleys for all patients, we advocate selective placement.

- Finally, certain patients (eg, bowel obstruction) may receive a Foley because of the admitting service’s preference. Discuss these cases with the admitting doc.

Avoiding catheters is a team sport. First, discuss every Foley insertion with the patient’s nurse; explaining your reasoning will help everyone change his or her practice regarding Foley use. Second, in EDs where a nurse “starts a patient up” by placing an IV, sending labs, and maybe placing a Foley, speak with your nursing director to ensure all Foleys are preceded by an order. Third, speak with your consultants. They are also trying to avoid CAUTIs, and may be open to changing traditional care patterns. Finally, speak with your patients. Some patients (eg, older men with congestive heart failure) request a Foley to assist with frequent urination during diuresis, yet most are agreeable to a bedside urinal if you explain the risk of infection.

Should you ever remove a Foley in the ED?

There is no rule that Foley catheters can’t come out in the ED. If you place a Foley to monitor urine output during a resuscitation, it can be removed once you’ve adequately resuscitated the patient. While the use of Foleys in trauma has decreased dramatically, their use has increased in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome or early sepsis. Once a patient leaves the ED, it may be days until the Foley is removed.

What is the cost of a Foley?

The direct cost to Medicare of placing a urinary catheter in the ED is $24.28 for the catheter and insertion supplies, $46.78 for the ED facility charge, and $31.03 if placed by an MD, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner. For commercially insured patients and the uninsured, the prices are higher. The small but real risk of a CAUTI is associated with much higher costs.

On your next shift, take a moment and think about each patient that gets a Foley. Can you avoid it? If it has served its purpose, can you take it out? The evidence to reduce Foley placement is strong enough that ACEP made it one of the five recommendations for emergency medicine in the Choosing Wisely campaign. If you want to learn more about how to reduce Foley use in the ED or want your ED to join a national quality improvement effort, check out the On the CUSP: STOP CAUTI collaborative (www.onthecuspstophai.org/on-the-cuspstop-cauti/emergency-department-improvement-intervention) for great resources on best practices to avoid Foleys and minimize CAUTI.

Dr. Lin is an attending emergency physician and a fellow in the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also serves as an instructor at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Lin is an attending emergency physician and a fellow in the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also serves as an instructor at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Schuur is Vice Chair of Quality and Safety and Chief of the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston. He also serves as assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Schuur is Vice Chair of Quality and Safety and Chief of the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston. He also serves as assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

References

- National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary, Table 19. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- Hazelett SE, Tsai M, Gareri M, Allen K. The association between indwelling urinary catheter use in the elderly and urinary tract infection in acute care. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:15.

- Gardam MA, Amihod B, Orenstein P, et al. Overutilization of indwelling urinary catheters and the development of nosocomial urinary tract infections. Clin Perform Qual Health Care. 1998;6:99-102.

- Gokula RR, Hickner JA, Smith MA. Inappropriate use of urinary catheters in elderly patients at a midwestern community teaching hospital. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:196-199.

- Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, et al. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:319-326.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Avoid Foley Catheters to Improve ED Patients’ Comfort, Reduce Costs”