Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 09 – September 2014Kids love to put odd objects in their mouths (and ears and nostrils and other interesting places), which can cause significant problems and lead to emergencies. Object location (eg, airway) and the object itself may also cause problems and severe tissue destruction. Button batteries are unique objects that warrant special concern and respect. While a button battery in the nostril can cause problems, button battery ingestion can be a more devastating problem.

Small Batteries, Big Problem

With the proliferation of small electronic devices, button batteries have become more prevalent, and the number of battery-related ED visits has increased significantly over the past 20 years. In 2009, about 6,000 children were seen in U.S. emergency departments for battery-related complaints; that’s more than 16 visits per day.1 Not surprisingly, cases involving children under four years of age, lithium batteries, and batteries more than 20 mm in diameter are more likely to result in poor outcomes.

Presentation, Imaging, and Diagnosis Button battery ingestion often presents similar to ingestion of other foreign bodies, with such symptoms as cough and gagging, drooling, dysphagia, labored breathing, or stridor. Patients may exhibit symptoms that are related to tissue damage, including vomiting, fever, irritability, or listlessness. In addition to obstruction/compression, batteries can cause chemical (especially alkaline) and electrical tissue damage; liquefaction necrosis and other damage can occur in a little as two hours.2

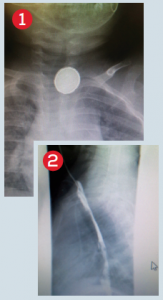

Vigilance and care are needed in diagnosing button battery ingestion. Fully 54 percent of fatalities due to button battery ingestion were misdiagnosed; many had nonspecific presentations, or the batteries were diagnosed as a swallowed coin.3 Fortunately, button batteries are radiopaque, coin-like objects that are evident on most plan films. Viewed en face, a button battery will have a halo rim (a ring of radiolucency just inside the outer edge of the object). Viewed on edge, a button battery may have a central bulge or step off (this can be difficult to appreciate if seen obliquely or with the newer, thinner lithium batteries).

Management

Treat any button battery ingestion as an emergency—time is of the essence to minimize local tissue damage. Removal can be difficult, especially because local tissue damage can lead to friable structures that can be further damaged by instrumentation. A battery should be removed under direct visualization. A surgical team often needs to be called. A helpful algorithm is found on the National Capital Poison Center website, http://www.poison.org/battery/guideline.asp.

In an asymptomatic patient, a battery in the stomach or beyond can be monitored and allowed to pass. Repeat radiographs are reasonable: repeat in four days for patients less than 6 years of age or for larger button batteries (more than 15 mm in diameter), and repeat in 10–14 days for older children or for a smaller battery. After that time, if the battery is still in the stomach, endoscopic removal is recommended. Note that strict anticipatory guidance and return precautions should be given, emphasizing the need for patients to be evaluated for any abdominal pain, fever, or vomiting.

Co-ingestion of a magnet with a button battery necessitates removal. After removal, some advocate for a delayed second-look endoscopy to ensure no damage has occurred. It is important to note that perforations and fistulas may develop up to 18 days after removal. Strictures can develop weeks and months after removal.

Even though button batteries represent a genuine hazard, emergency physicians alert to the signs and symptoms of button battery ingestion can effectively manage them and help their patients achieve good outcomes.

Case 1

A 3-year-old male was well until he vomited bright-red blood and became unresponsive; EMS transported the patient to the hospital. He arrived in asystole cardiac arrest, with blood around his nose and mouth, and received continuous pediatric advanced life support. Despite this, he expired.

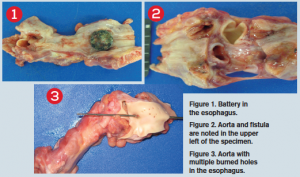

At postmortem, a button battery was found impacted in the esophagus at the level of the transverse aorta. There was a fistula connecting the esophagus and aorta, with the esophagus packed with bright-red blood and with gastric content of large dark-colored blood clots. The small and large bowels were also found to be packed with dark-colored stool.

Case submitted by Eugene Varghese, MD, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, and David Woodkotch, MD, chief resident of emergency medicine at Rutgers.

Case 2

A 5-year-old female who was “playing around” with her grandma’s battery while hanging out in her grandma’s car ingested a button battery. She waited a few hours before telling anyone and was seen about six hours after ingestion. She complained of a sore throat and had no difficulty with secretions or breathing. Lateral and anteroposterior chest X-rays showed a battery lodged in her upper esophagus (see Figure 1).

We used propofol for endoscopy done by a pediatric gastroenterologist while in the ED. She was admitted by pediatrics after retrieval of the battery for concern of necrotic tissue in the upper esophagus noted by the gastroenterologist (see Figure 2). She was initially placed on antibiotics by us and steroids by the gastroenterologist out of concern for possible perforation and/or mediastinitis (which did not occur). Figure 3 shows the button battery after retrieval.

Case and photos submitted by Peter Chase, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacy practice and science at The University of Arizona in Tucson.

Case 3

A 14-month-old male was seen at an outside hospital on a Saturday in late April for a choking episode. An X-ray (see Figure 1) was done, and physicians there thought the round metallic foreign body was a coin and asked the family to return in 24 hours. The patient was seen again on Sunday. Another chest X-ray (anteroposterior only) was done, and the esophageal coin was seen again. Because it had not moved, the patient was transferred to our hospital. On arrival, we looked at the X-ray and saw that the foreign body was clearly a battery.

Surgery was called, and the patient was taken to the operating room. An initial swallow study done the day after retrieval appeared normal. The patient did well but returned two weeks later with coughing and aspiration and had developed a tracheoesophageal fistula (see Figure 2). Visit www.ACEPNow.com for a video of this case.

Case, photos, and video submitted by Cindy Nielsen, MD, The Children’s Hospital at OU Medical Center in Oklahoma City.

Dr. Fox is associate professor of adult and pediatric emergency medicine at Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, North Carolina.

- Sharpe SJS, Rochette LM, Smith GA. Pediatric battery-related emergency department visits in the United States, 1990-2009. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1111-7.

- National Capital Poison Center. Mechanisms of battery-induced injury. National Capital Poison Center Web site. Available at: http://www.poison.org/battery/mechanism.asp. Accessed June 12, 2014.

- Litovitz T1, Whitaker N, Clark L, et al. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1168-77.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Button Batteries a Swallowing Hazard for Children”