The four basic considerations in cases such as these are:

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 04 – April 2023- Awake intubation versus intubation after induction agents

- Noninvasive techniques versus invasive techniques (surgical

or percutaneous airway)

- Video-assisted laryngoscopy as the initial approach to intubation,

and

- Preservation versus ablation of spontaneous ventilation1

Findings

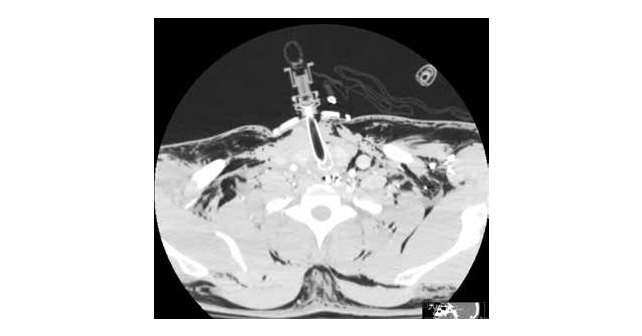

CT may demonstrate distortion of the airway and surrounding structures, fracture or tear of larynx or trachea, edema, and hematoma in a case of blunt airway injury.7 (see Figure 2).

Since cases of blunt injury to the airway are rare, a unified standard of care for emergency invasive airway access would of necessity be difficult to define. The American Society of Anesthesiology guidelines for invasive airway access in their practice guidelines list surgical or percutaneous airway, jet ventilation, and retrograde intubation.1

Indications for urgently securing the airway generally have been cited as respiratory distress, hypoxia, severe agitation, inability to protect the airway (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale of 8 or less), altered mental status, and hematoma or mucosal edema compromising the airway, as from smoke and chemical burns. A surgical airway may be mandated in the hypoxic or hypotensive patient who cannot be intubated.8 Alternatives to surgical intervention in the patient with respiratory distress include awake intubation, video-assisted laryngoscopy, intubating stylets or tubechangers, supraglottic airways such as laryngeal mask airways, rigid laryngoscopic blades, fiberoptic-guided intubation, and lighted stylets or light wands.7

To The Operating Room

The patient was transported from the ED with the aforementioned 6-0 airway in place. Multiple shattered pieces of cartilage were found by the operating otolaryngologist. The patient underwent a laryngotracheal reconstruction with rib graft and primary repair of a laryngotracheal separation at the right cricothyroid joint. A T-tube was placed at the third tracheal ring (see Figure 3), and a 6-0 proximal XLT Shiley tube placed. He was discharged 14 days after the injury, neurologically intact.

Conclusions

Blunt neck traumas producing a situation of “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” are relatively rare, and consistently challenging. Surgical management must always be an option.

Dr. Glauser is professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University at MetroHealth Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio.

References

- Updated by the Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):251-270.

- McConnell DB, Trunkey DD. Management of penetrating trauma to the neck. Adv Surg. 1994;27:97-127.

- Kummer C, Netto FS, Rizoli S, Yee D. A review of traumatic airway injuries: Potential implications for airway assessment and management. Injury. 2007;38:27-33.

- Haran C, Kong V, Cheung C, et al. Managing the acutely threatened airway following head and neck trauma- requiem for cricothyroidotomy? Surg Pract Sci. 2022;11:100-124

- Lowe E, Patil S. Management of subacute airway emergency after blunt neck trauma. BMJ. 2017;356:j141.

- Srivastava B, Solanki T. Retropharyngeal hematoma-an unusual bleeding site in an anticoagulated patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:294.

- Jain U, McCunn M, Smith CE, Pittet J-F. Management of the traumatized airway. Anesthesiology. 2016:124 (1);200-206.

- Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1-20.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Blunt Tracheal Injury Creates Difficult Airway”