A 34-year-old male was involved in a motorcycle rollover. His vehicle hit a pole, and he was hit in the throat with the handlebars of his bike. He presents alert and awake, with gross facial and neck swelling, and no history of loss of consciousness. His Glasgow Coma Scale is 15. Notable on his physical examination is subcutaneous emphysema diffusely, including crepitus to palpation of radial pulses, and crepitus in his face, neck, torso, and scrotum. X-ray confirms subcutaneous emphysema (see Figure 1). There are no external lacerations.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 04 – April 2023

FIGURE 1: Initial chest X-ray taken supine demonstrating massive subcutaneous emphysema. Of note: Bilateral pneumothoraces are visible on the chest CT (See Figure 2) but are not clear on the initial chest X-ray. He received chest tubes thereafter.

To protect his airway, an awake intubation is planned. He is administered nebulized lidocaine and ketamine. He develops severe respiratory distress and becomes unable to phonate. Intubation with a Glidescope is unsuccessful, and he is biting the tube.

The surgery team performed an emergency surgical airway.

The surgical procedure note read as follows: “His midline had been marked. Incision with a 10 blade was made over this line. The scalpel was used to divide the subcutaneous tissue, which was bleeding profusely. Then I suddenly encountered massive spewing of dark red non-pulsatile blood into the field.

“With suctioning, gauze packing, and retractors, I was able to somewhat control the bleeding, and I used my finger to explore the wound. I felt the laryngeal prominence and traced this down to a boggy area that I hoped was the cricoid membrane. There were crunchy things in the area which I assumed were shattered pieces of cartilage. I used a hemostat to bluntly poke a hole into the boggy area and spread to dilate the hole. I used my finger to explore the hole and initially felt the inside of the larynx, so I knew I was in the airway.

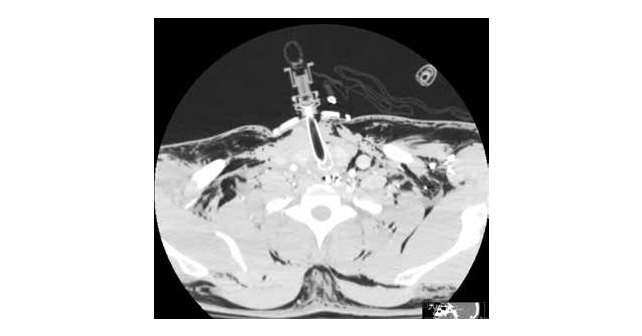

FIGURE 2: CT chest demonstrating large bilateral pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema. Laryngeal-tracheal separation may occur. Insertion of an endotracheal tube may cause separation of the trachea from the larynx, if the connection is tenuous. A transected cervical trachea may retract into the mediastinum and have to be surgically retrieved/extracted to establish an airway.

“At a very sharp angle inferiorly, I was able to feel tracheal rings. I passed a pediatric bougie into the trachea and then over this slid a 6-0 cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) into the airway. One of my colleagues blew up the balloon and began ventilating the patient. The endotracheal tube is sutured to the skin of the anterior neck with 0 silk. End-tidal CO2 confirms placement in the trachea.”

How Difficult Airways Present

The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ practice guidelines define a difficult airway as a clinical situation in which a conventionally trained anesthesiologist experiences difficulty with facemask ventilation of the upper airway, difficulty with tracheal intubation, or both. Difficult laryngoscopy is defined as inability to visualize any portion of the vocal cords after multiple attempts. Difficult tracheal intubation entails multiple attempts at intubation, in the presence or absence of tracheal pathology.1

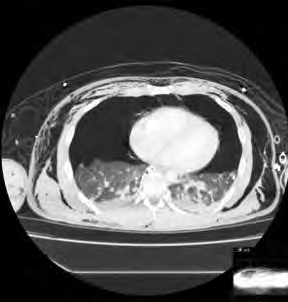

FIGURE 3: CT demonstrating T-tube in airway, at approximately the C3-4 level, along with air diffusely in soft tissue. An important takeaway is that if the tracheostomy tube is dislodged, the patient cannot be intubated from above. The neck must be re-explored to establish an airway. The author does not in general recommend CT to confirm airway placement. In fact, there was positive end tidal CO2 after the 6-0 cuffed ETT was sutured into the patient’s airway.

There are many non-traumatic disease states which may contribute: ankylosis, degenerative osteoarthritis, subglottic stenosis, lingual thyroid, tonsillar hypertrophy, or congenital nontraumatic abnormalities such as Down syndrome, Pierre Robin, and Treacher-Collins. For purposes of this discussion, we will concentrate on traumatic injury.

Tracheobronchial injury occurs in an estimated 10 to 20 percent of patients with penetrating trauma to the neck.2 In a retrospective review of 12,187 patients treated at a civilian trauma center in Toronto over 16 years, 36 patients (0.3 percent) suffered blunt airway injury.3 Blunt trauma to the neck may be more complicated. Of course, in these cases, intubation directly through the wound is not an option. Over recent decades, the availability of video-laryngoscopy (VL) and fiberoptic intubation/ bronchoscopy (FOB) have reduced both the rate of failed intubation and the need to perform emergency surgical airways.

Another report enumerating over 12,000 trauma cases over a seven-year period listed 242 patients requiring a surgical airway. When only the 3,271 patients with trauma to the head and neck were considered, a mere 51 cases required a surgical airway, and of these, 47 cases made it to the operating room for a surgical tracheostomy.4 Since traumatic airway injury is rare, assessment and management are not well characterized. Trauma may also entail a variety of contributing factors. For example, retropharyngeal hematomas have been reported following cervical spine injury, foreign body ingestion, central line placement, and coagulation disorders.5,6

Other measures may help, although they were of limited value in the above case. Opportunities for supplemental oxygen include oxygen delivery by nasal cannula, facemask or laryngeal-mask airway, and blow-by. Clearly, in the case above, these measures were temporizing at best. In fact, the patient’s arterial blood gas just prior to surgical intervention revealed a pH of 7.105, pCO2=87, and pO2=62.

The four basic considerations in cases such as these are:

- Awake intubation versus intubation after induction agents

- Noninvasive techniques versus invasive techniques (surgical

or percutaneous airway)

- Video-assisted laryngoscopy as the initial approach to intubation,

and

- Preservation versus ablation of spontaneous ventilation1

Findings

CT may demonstrate distortion of the airway and surrounding structures, fracture or tear of larynx or trachea, edema, and hematoma in a case of blunt airway injury.7 (see Figure 2).

Since cases of blunt injury to the airway are rare, a unified standard of care for emergency invasive airway access would of necessity be difficult to define. The American Society of Anesthesiology guidelines for invasive airway access in their practice guidelines list surgical or percutaneous airway, jet ventilation, and retrograde intubation.1

Indications for urgently securing the airway generally have been cited as respiratory distress, hypoxia, severe agitation, inability to protect the airway (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale of 8 or less), altered mental status, and hematoma or mucosal edema compromising the airway, as from smoke and chemical burns. A surgical airway may be mandated in the hypoxic or hypotensive patient who cannot be intubated.8 Alternatives to surgical intervention in the patient with respiratory distress include awake intubation, video-assisted laryngoscopy, intubating stylets or tubechangers, supraglottic airways such as laryngeal mask airways, rigid laryngoscopic blades, fiberoptic-guided intubation, and lighted stylets or light wands.7

To The Operating Room

The patient was transported from the ED with the aforementioned 6-0 airway in place. Multiple shattered pieces of cartilage were found by the operating otolaryngologist. The patient underwent a laryngotracheal reconstruction with rib graft and primary repair of a laryngotracheal separation at the right cricothyroid joint. A T-tube was placed at the third tracheal ring (see Figure 3), and a 6-0 proximal XLT Shiley tube placed. He was discharged 14 days after the injury, neurologically intact.

Conclusions

Blunt neck traumas producing a situation of “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” are relatively rare, and consistently challenging. Surgical management must always be an option.

Dr. Glauser is professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University at MetroHealth Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio.

References

- Updated by the Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):251-270.

- McConnell DB, Trunkey DD. Management of penetrating trauma to the neck. Adv Surg. 1994;27:97-127.

- Kummer C, Netto FS, Rizoli S, Yee D. A review of traumatic airway injuries: Potential implications for airway assessment and management. Injury. 2007;38:27-33.

- Haran C, Kong V, Cheung C, et al. Managing the acutely threatened airway following head and neck trauma- requiem for cricothyroidotomy? Surg Pract Sci. 2022;11:100-124

- Lowe E, Patil S. Management of subacute airway emergency after blunt neck trauma. BMJ. 2017;356:j141.

- Srivastava B, Solanki T. Retropharyngeal hematoma-an unusual bleeding site in an anticoagulated patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:294.

- Jain U, McCunn M, Smith CE, Pittet J-F. Management of the traumatized airway. Anesthesiology. 2016:124 (1);200-206.

- Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1-20.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Blunt Tracheal Injury Creates Difficult Airway”