Case

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with bizarre behavior. He was found by bystanders running naked in the street and 911 was called. On initial ED presentation, he was awake and alert and appeared anxious. He attempted to get off the stretcher, and yelled, “I’m out of here! You can’t keep me here. I know my rights!”

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 01 – January 2023Problem: Does this patient have decisional capacity to refuse ED care?

Clinical questions arise regularly in the ED. How should such on-shift clinical questions be researched? There are numerous options for answers to clinical questions. Clinical textbooks such as “Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide” or “Rosen’s Emergency Medicine” are valuable resources for studying and answering clinical questions. Internet search engines may provide current information. Online review sources such as UpToDate are rapidly accessible. Review of the literature is important, but can be difficult to accomplish in real time in the clinical environment.

Organizations may provide guidance on important clinical issues. To answer this question, let’s turn to the American Medical Association (AMA) and The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). The AMA has an extensive list of policies. AMA policies can be searched using the AMA Policy Finder.1 The policy “Decisions for Adult Patients who Lack Capacity”2 states:

Respect for patient autonomy is central to professional ethics and physicians should involve patients in health care decisions commensurate with the patient’s decision-making capacity. Even when a medical condition or disorder impairs a patient’s decision-making capacity, the patient may still be able to participate in some aspects of decision making. Physicians should engage patients whose capacity is impaired in decisions involving their own care to the greatest extent possible, including when the patient has previously designated a surrogate to make decisions on his or her behalf.

The ACEP Code of Ethics includes “Principles of Ethics,” “Overview of Ethics,” and a “Compendium of ACEP Policy Statements on Ethical Issues.”3 This document provides the following guidance:

Emergency physicians may treat without securing informed consent when immediate intervention is necessary to prevent death or serious harm to the patient, when the patient lacks decision making capacity, and when no one legally authorized to consent on behalf of the patient is available. These are, however, limited exceptions to the duty to obtain informed consent. When the initiation of treatment can be delayed without serious harm, informed consent must be obtained. Even if all the information needed for an informed consent cannot be provided, emergency physicians should, to whatever extent time allows, inform the patient (or, if the patient lacks capacity, a surrogate) about the treatment they are providing, and may not violate the explicit refusal of treatment of a patient with decision-making capacity. In some cases, for personal and cultural reasons, patients ask that information be given to family or friends and that these third parties be allowed to make treatment choices for the patient. Patients may, if they wish, waive their right to informed consent or delegate decision-making authority for their care to others. Other exceptions to the duty to obtain informed consent apply when treatment is necessary to protect the public health and in a limited number of emergency medicine research protocols where obtaining consent is not feasible, provided that these research protocols satisfy the requirements of federal research regulations and are approved by appropriate review bodies.

Review of the medical literature using Pub-Med may also provide guidance. A literature search using the term “decisional capacity in the emergency department” found an article published in 2017 by members of the ACEP Ethics Committee, entitled “Refusal of Emergency Medical Treatment: Case Studies and Ethical Foundations.”4 The article states:

Decisional capacity (decisionmaking capacity) is essential to patients’ autonomous medical decisionmaking. The assessment of decisional capacity is an essential skill for emergency physicians. The burden of proof is on the physician to determine whether the patient possesses appropriate decisional capacity. Patients who do not possess it should not be allowed to refuse necessary medical treatment until decisional capacity is restored. There may be significant variation in providers’ assessment of decisional capacity, which underscores the need for a better understanding of decisional capacity and its assessment in the ED environment. Capacity is composed of four essential elements: understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and expression of choice. Thus, an individual must be able to understand the information delivered, appreciate how to apply it to his or her own situation, reason to make an appropriate decision, and communicate that choice.

Case Summary

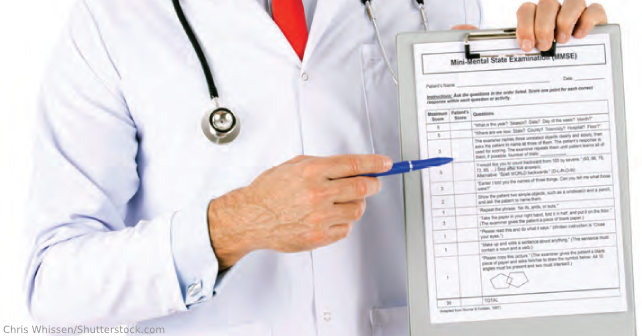

Assessment of decisional capacity is essential. Decisional capacity is dynamic and may vary over time, as the patient’s mental status or clinical or environmental factors may change. In cases where decisional capacity is unclear, standardized tests may be valuable in the determination of capacity. One standardized test which is easily administered in emergency medicine is the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE).5 Low scores on the MMSE might indicate a patient might lack capacity but normal scores do not assure capacity is present. Decisional capacity may be impaired by numerous conditions, including dementia, intoxication, psychiatric conditions, language impairment, cultural issues, physical communication impairments, severe pain, organic disease states and numerous other conditions.6

Decisional capacity is frequently impaired in cases of impaired consciousness, intoxication with alcohol, drugs, or toxins, severe pain, impaired cognition or any condition rendering a patient unable to participate in medical decision making. In these circumstances, and when no one legally authorized to act on the patient’s behalf is immediately available, physicians should act in the patient’s best interest according to what a “reasonable person” would want in similar circumstances. If the patient is unable or unwilling to cooperate with assessment of decisional capacity, he should be detained until assessment can safely be completed to allow respect for patient autonomy when the patient is fully capable of medical decision making.

Dr. Marco is professor of emergency medicine at Penn State Health-Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and associate editor of ACEP Now.

Dr. Marco is professor of emergency medicine at Penn State Health-Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and associate editor of ACEP Now.

References

- AMA policy finder. AMA website. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder. Accessed October 6, 2022.

- AMA. Decisions for adult patients who lack capacity: Code of medical ethics opinion 2.1.2. AMA website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/decisions-adult-patients-who-lack-capacity. Published 2016. Accessed October 6, 2022.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Policy statement: Code of ethics for emergency physicians. ACEP website. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/policy-statements/code-of-ethics-foremergency-physicians.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed October 6, 2022.

- Marco CA, Brenner JM, Kraus CK, McGrath NA, Derse AR, ACEP Ethics Committee. Refusal of emergency medical treatment: Case studies and ethical foundations. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):696-703. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.015.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-98.

- Freer J. Decision making in an incapacitated patient. Journal of Clinical Ethics. 1993;4:55-58.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Does This Patient Have Decisional Capacity?”