Portions of this study have been presented as a poster abstract at the Case Western Reserve University 2021 by Martha L. Lepow MD, and Irwin H. Lepow, MD, PhD, during the Virtual Medical Student Research Day.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 12 – December 2022Case

A 26-year-old male with a past medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (CD4 count of 981) and hepatitis C virus infections presented to the emergency department for abdominal pain. His pain started six days prior, originally located in the lower left quadrant. The pain was described as cramping and worsened with having a bowel movement. The patient also noted intermittent fevers and chills.

He had been seen two days prior to our emergency department visit at an outside hospital. The previous work-up included a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed perirectal inflammation concerning for proctitis. Rectal swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia were performed; however, results were still pending. Labs revealed a mild transaminitis (alanine transaminase (ALT) 53, aspartate transaminase (AST) 43). Otherwise, complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), and lipase levels were within normal limits. The patient was treated with an intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg and prescribed seven days of doxycycline, which he had been taking as prescribed.

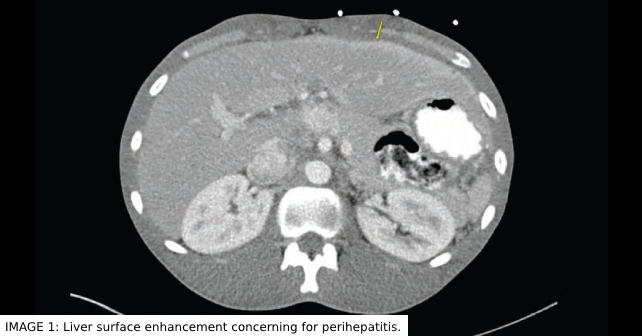

In our emergency department (ED), blood pressure was 115/67, pulse 65, temperature 98.3 F, respiratory rate 16, SpO2 99 percent. Physical exam was significant for lower left quadrant abdominal tenderness without peritoneal signs. The patient also had a new right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal tenderness. BMP, CBC, and lipase were within normal limits. LFTs showed improving AST of 41 and ALT of 37. Due to the acute worsening of his abdominal pain and new RUQ abdominal pain on exam, a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered. CT scan confirmed known rectal wall thickening concerning for proctitis. However, new findings included liver surface enhancement concerning for perihepatitis (see Image 1). Given the high likelihood of gonorrhea or chlamydial origin of his proctitis, there was concern that this may be Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome (FHCS). Rectal swabs were again performed. Intravenous (IV) Cefoxitin and Doxycycline were administered. The patient was admitted to the hospital, where his pain improved. Rectal cultures were positive for Chlamydia trachomatis. An infectious disease physician was consulted and recommended a 21-day course of doxycycline. The patient was discharged two days later.

Pathophysiology

FHCS, also known as perihepatitis, is a rare complication of chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). It is characterized by inflammation of the liver capsule and surrounding peritoneum with “violin-string” adhesion formation. FHCS is usually found in sexually active women between 15–30, with incidence ranging from four to 14 percent in individuals with PID. The condition was first reported in the English language in 1930 by Dr. Curtis, who noted extensive adhesions between the anterior surface of the liver and anterior abdominal wall in a female patient presenting with gonococcal salpingitis.1 In 1934, Dr. Fitz-Hugh reported similar cases in which three women presented with RUQ abdominal pain due to acute gonococcal peritonitis that showed liver capsule adhesions.2 Although Neisseria gonorrhoeae was initially thought to be the primary cause of FHCS, Chlamydia trachomatis has also been shown to be a frequent causative agent.3 Infectious agents associated with PID are thought to be disseminated either through direct spread from reproductive organs to the peritoneal cavity, hematogenous spread, or lymphatic spread. Some studies have also hypothesized that FHCS may be the result of an exaggerated immune response to C. trachomatis due to increased serum titers of antichlamydial immunoglobulin G antibodies.4

FHCS commonly presents with RUQ abdominal pain that can be pleuritic. It can be associated with fever, nausea, vomiting, headache, and overall malaise. In some cases, a friction rub may be auscultated along the right anterior costal margin. Liver enzyme levels and white blood cell counts are usually normal or slightly elevated, while erythrocyte sedimentation rate and c-reactive protein are often elevated.4 Since the clinical presentation of FHCS can mimic many other diseases localized to the RUQ, it is often mistaken for processes such as cholecystitis, hepatitis, acute pyelonephritis, or liver abscess. CT scan may show increased perihepatic enhancement or capsular thickening. However, direct visualization of perihepatic adhesions through laparoscopy is the only way to definitively diagnose. FHCS in men is exceedingly rare and possibly underrecognized.

Discussion

There is a paucity of case reports of FHCS occurring in men. It is unknown if this is due to a lower prevalence of this complication, or just underrecognized. Case reports in men show a range of primary infections that led to FHCS. Urethritis, proctitis, and orchitis/epididymitis have been reported as initial pathologies prior to the formal diagnosis of FHCS.5,6,8,9 Given that there is no direct extension into the peritoneal cavity from these primary sites, unlike with direct extension from fallopian tubes in women, it is thought that hematogenous or lymphatic spread is responsible for the syndrome in men.8 Causative microorganisms are similar to those that affect women. Chlamydia and gonorrhea appear to be the most common organisms isolated in reported cases.5,6,8 Although definitive diagnosis is through direct visualization through laparoscopy, if there is a clinical concern, contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is considered first-line imaging.9 Management of this disorder in men has not been thoroughly investigated. Antibiotic therapy should be pathogen directed, but when a pathogen is unknown and the patient requires admission, empiric therapy is warranted. We opted to treat as we would for PID in women—namely intravenous cefoxitin or cefotetan with doxycycline. With chlamydial sources, 21 days of doxycycline appears to be appropriate antibiotic management to treat this condition.8 However, when antibiotic management fails, direct lysis of adhesions via laparoscopy may be indicated for definitive therapy if symptoms continue.10

FHCS should be considered in any man who presents with worsening right upper quadrant abdominal pain or pleuritic right lower chest pain with recent or current symptoms of sexually transmitted disease such as urethritis, orchitis/epididymitis, or proctitis. Serologic testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia should be promptly performed and CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis can be utilized if clinical concern exists. Antibiotics with coverage against chlamydia and gonorrhea should be promptly initiated if a specific microorganism has yet to be identified. Patients should be informed that, if their abdominal pain does not improve with antibiotics alone, surgical intervention may be necessary.

Dr. Resendes is a resident physician at Case Western Reserve Metrohealth, Cleveland Clinic Emergency Medicine Residency, Department of Emergency Medicine, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Resendes is a resident physician at Case Western Reserve Metrohealth, Cleveland Clinic Emergency Medicine Residency, Department of Emergency Medicine, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Boruah is MS4 at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Boruah is MS4 at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Israeli is an attending physician and assistant professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University and staff physician at the Emergency Services Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Cleveland, Ohio.

References

- Curtis A. A cause of adhesions in the right upper quadrant. JAMA. 1930;94:1221-1222.

- Fitz-Hugh T Jr. Acute gonococcic peritonitis of the right upper quadrant in women. JAMA. 1934;102:2094-2096.

- Peter NG, Clark LR, Jaeger JR. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome: A diagnosis to consider in women with right upper quadrant pain. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(3):233-9.

- Money DM, Hawes SE, Eschenbach DA, et al. Antibodies to the chlamydial 60 kd heat-shock protein are associated with laparoscopically confirmed perihepatitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(4):870-7.

- Takata K, Fukuda H, Umeda K, et al. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in a man positive for Chlamydia trachomatis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11(4):338-342.

- Lisičar I, Begovac J, Zekan Š. A rare case of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome caused by Chlamydia trachomatis in an HIV-positive male patient. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X18823592.

- Baek HC, Bae YS, Lee KJ, et al. [A case of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in a male]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55(3):203-7. Korean.

- Nardini P, Compri M, Marangoni A, et al. Acute Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in a man due to gonococcal infection. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(3):e59-62.

- Jeong TO, Song JS, Oh TH, Lee JB, Jin YH, Yoon JC. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in a male patient due to urinary tract infection. Clin Imaging. 2015;39(5):917-9.

- Saurabh S, Unger E, Pavlides C. Fitz -Hugh-Curtis syndrome in a male patient. J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012(3):12.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Fitz-Hugh Curtis Syndrome in a Male with HIV”