Emergency physicians encouraged to review guidelines for diagnosing, treating this parasitic disease as infection rates reach highest level in 30 years

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014In November 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a document announcing that 2011 was the year with the highest number of reported malaria cases in the United States since 1971. This article summarizes the essential elements of the CDC malaria surveillance in 2011.

Identifying and Treating Malaria

It is not unusual for travelers who have returned to the United States to seek care in the emergency department for their illnesses. Malaria should be considered in a febrile individual who provides a history of travel to an area where malaria transmission is known. The signs and symptoms of malaria are variable and can include fever, chills, myalgia, malaise, headaches, back pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and cough. These nonspecific manifestations can easily be confused with more commonly encountered viral and bacterial infections.

A common method for the diagnosis of malaria is microscopic examination of peripheral blood for parasites (thick and thin blood smear). This test not only permits a rapid determination of the presence or absence of parasites but also allows for identification of the parasite species and the percentage of infected red blood cells.

The choice of antimalarial agents is multifactorial. It is dependent on the severity of the infection; the ability to identify and quantify the density of the Plasmodium species; and the geographic origin of the parasite, which helps in predicting resistance patterns. Severe malaria is defined as a case in the presence of one or more of the following manifestations: neurologic symptoms (eg, altered mental status, seizures), renal failure, severe anemia, pulmonary edema, circulatory shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acidosis, jaundice, or greater than or equal to 5 percent parasitemia.

It is imperative to consult the CDC and an infectious-diseases specialist as soon as possible when encountering severe malaria. Severe malaria is treated intravenously with quinidine gluconate plus one of the following: doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin. A highly effective alternative to quinidine gluconate is intravenous artesunate, which is available as an investigational new drug through the CDC. Intravenous artesunate should be followed by one of the following: atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone), doxycycline, clindamycin, or mefloquine.1

In situations when the Plasmodium species is not known, a presumptive treatment regimen for a P. falciparum infection should be initiated. Indications for hospitalization include the inability to exclude P. falciparum infection; severe illness (as outlined above); and infection in infants, pregnant women, and those with severe underlying chronic medical conditions.

In 2011, the CDC received 1,925 reported cases of malaria among persons in the United States and its territories. In comparison to 2010, there was a 14 percent increase in the number of reported cases in 2011.

Malaria Statistics

In 2011, the CDC received 1,925 reported cases of malaria among persons in the United States and its territories. In comparison to 2010, there was a 14 percent increase in the number of reported cases in 2011, and it was the highest number of malaria cases reported since 1971 (N=3,180).2,3

The majority of cases occurred among U.S. residents (1,189 cases, 62 percent). The definition of U.S. residents included both civilian and US military personnel, regardless of legal citizenship. There was a significant increase in the number of reported malaria cases among U.S. military personnel in 2011 compared to 2010 (91 versus 45). For the remainder, 386 (20 percent) cases occurred among foreign residents, and 350 (18 percent) cases occurred among patients with unknown or unreported resident status. The definition of foreign residents included any individuals who held resident status in a country other than the United States.

The majority of cases (N=1,920) were classified as imported, defined as those acquired outside of the United States and its territories. The remaining five cases were categorized as laboratory-acquired (1), transfusion-related (1), congenital (2), and cryptic (1). Cryptic malaria was defined as a case for which epidemiologic investigations could not identify a plausible mode of acquisition. This term was applied primarily to cases found in countries where malaria was not endemic.

The infecting species of Plasmodium was identified in 1,490 (77 percent) of 1,925 reported cases. Almost all infections were due to a single species of Plasmodium. Only 21 cases (1 percent) were due to a mixed infection with two different species of Plasmodium. Overall, the majority of infections were due to P. falciparum (49 percent), followed by P. vivax (22 percent), P. malariae (3 percent), and P. ovale (3 percent).

A common method for the diagnosis of malaria is microscopic examination of peripheral blood for parasites. This test not only permits a rapid determination of the presence or absence of parasites but also allows for identification of the parasite species and the percentage of infected red blood cells.

Of the imported cases (N=1,920), data on the region of acquisition of infection were reported and available in 1,655 cases. Among these cases, 1,144 (69 percent) were acquired in Africa, 363 (22 percent) in Asia, 140 (8 percent) in the Americas, 7 (0.4 percent) in Oceania, and 1 in the Middle East. The majority (63 percent) of the cases acquired in Africa were from the countries in the western part of Africa, specifically including, but not limited to, Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.

Most cases from Asia, in the order of decreasing frequency, were acquired in India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Thailand. The number of cases acquired in Afghanistan was significantly higher compared to 2010 (96 versus 43), mainly due to an increased number of infections among US military personnel serving in Afghanistan. The majority of cases from Central America and the Caribbean were from Haiti and Honduras, while in South America most cases were from Guyana and Brazil. With the exception of one case, all cases from Oceania were from Papua New Guinea. There was only one case reported from the Middle East; however, the country of acquisition as well as the involved Plasmodium species were unknown.

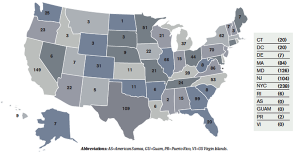

In the United States, the top 10 states reporting malaria cases, in the order of decreasing frequency, were New York (238), California (149), Maryland (126), Florida (120), Texas (109), New Jersey (104), Georgia (99), Virginia (86), Massachusetts (84), and Pennsylvania (70) (see Figure 1). In comparison to the other states, Massachusetts reported the highest rate of increase in cases of malaria in 2011 (133 percent, 36 in 2010 versus 84 in 2011).

The purpose of travel at the time of malaria acquisition was reported by 871 (80 percent) of the 1,095 US civilians with imported malaria. The definition of US civilians excluded US military personnel. The most common reasons for travel among civilians included visiting friends or relatives (70 percent), missionary-related work (11 percent), and travelling for business (9 percent). Among foreign residents for whom the purpose of travel to the United States was known (303), 172 (57 percent) were recent immigrants or refugees and 80 (26 percent) were among those visiting friends or relatives.

With respect to the seasonality of malaria diagnosed in the United States during 2011, the reporting peaked in August for P. falciparum and P. vivax infections. This peak likely correlated with peak travel times during summer holidays. The majority of patients (86 percent) had their malarial symptoms on or after arrival to the United States. The remaining 14 percent had an onset of symptoms before arrival to the United States. Of those with the onset of symptoms after arrival to the United States, regardless of the involved Plasmodium species, most experienced their symptoms within one month after the date of arrival.

Among the individuals who reported taking a specific chemoprophylaxis agent, 83 percent took a CDC-recommended medication, while the remaining 17 percent took an agent that was not CDC-recommended for the area visited. Of those taking the CDC-recommended chemoprophylaxis and for whom adherence was known, almost 70 percent reported nonadherence to the proposed chemoprophylaxis regimen. Past history of malaria was known for 67 percent of the imported cases, of which 21 percent reported a history of infection within the past year. Based on the availability of data, 23 probable relapses were identified (22 due to P. vivax and one due to P. ovale). Relapsing malaria was defined as a recurrence of disease after its apparent cure. Relapses are caused by reactivation of dormant liver-stage parasites (hypnozoites) of P. vivax and P. ovale.

Eighty percent of infections were reported in individuals 18–64 years of age, 15 percent in those younger than age 18, and 5 percent in those age 65 or older. At the time of malaria acquisition among the pediatric subjects, 51 percent were U.S. civilians, 34 percent had foreign-resident status, and 16 percent had unknown resident status. Of the U.S. civilian children, 6 percent were younger than 24 months, 18 percent were 2–4 years, 42 percent were 5–12 years, and 34 percent were 13–17 years of age. A majority of the infections in these patients were attributed to travel to Africa for the purpose of visiting friends or relatives. Of the children with known chemoprophylaxis information, 49 percent reported having taken some type of malaria chemoprophylaxis. However, only 50 percent of these patients took the appropriate regimen, and the majority (60 percent) reported nonadherence to the recommended chemoprophylaxis regimen.

Thirty-seven cases of malaria were reported among pregnant women, of whom 30 percent were considered severe infections. In the absence of fulfilling the specific clinical criteria for severe infection, patients who were treated with artesunate, quinidine, or an exchange blood transfusion were also considered as having severe infections. Of note, exchange blood transfusion for the treatment of severe malaria is no longer recommended.4 Most (79 percent) infections in pregnant women were due to P. falciparum, followed by P. vivax (18 percent).

Among the 1,596 cases for which the disposition information was available, 1,047 (66 percent) were hospitalized. The majority (61 percent) of admissions were due to P. falciparum, followed by P. vivax (18 percent) infections.

Of the 1,920 cases of imported malaria, 1,645 (86 percent) were categorized as uncomplicated infections. Most of these patients (72 percent) were treated appropriately, according to the CDC guidelines, when treatment information was available; however, almost 30 percent received inappropriate treatment. There was a noteworthy decrease in patients with uncomplicated disease being treated appropriately compared to the previous year (72 percent in 2011 versus 87 percent in 2010).

Fourteen percent of all cases were classified as severe malaria, with almost 75 percent due to P. falciparum. Five patients died. In comparison to the previous year, there was a significant increase in the number of severe cases (14 percent in 2011 versus 11 percent in 2010). A majority of the infections (84 percent) occurred in patients older than age 17. Among children, those younger than age 5 were more likely to have severe disease than those who were older. There was no association found between severe disease and age greater than 64 years. Of those with known prophylaxis information, 26 percent reported taking a recommended malaria chemoprophylaxis; however, only 23 percent reported compliance with the suggested regimen. Most patients experienced severe anemia (19 percent) or renal failure (16 percent). With respect to the treatment, inappropriate treatment was more commonly observed in patients with severe disease than in those with uncomplicated infections.

The CDC provides numerous resources, including telediagnosis, for clinicians for malaria prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment recommendations. Malaria-treatment recommendations can be obtained online at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment or by calling the Malaria Hotline at 770-488-7788 or toll-free at 855-856-4713 during regular business hours or the CDC’s Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100 during evenings, weekends, and holidays.

Dr. Abrahamian is clini cal professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of education in the department of emergency medicine at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center in Sylmar, Calif.

cal professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of education in the department of emergency medicine at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center in Sylmar, Calif.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for treatment of malaria in the United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/resources/pdf/treatmenttable.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria surveillance-United States, 2011. MMWR. 2013;62(No. SS-5).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria surveillance-United States, 2010. MMWR. 2012;61(No. SS-2).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Exchange transfusion for treatment of severe malaria no longer recommended. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/new_info/2013/exchange_transfusion.html. Accessed January 24, 2014.

One Response to “CDC Reports Record Number of Malaria Cases in the U.S”

August 6, 2019

Paul E. KuneliusI was discharged from the Army on 08/23/1967. I served in Vietnam from Sept. of 1966 to August of 1967. In the month of Feb. 1969 I came down with malaria and was treated at the VA and was in the hospital for one week. I live in Massachusetts and have for my whole life. My questions are was it possible to contact malaria in MA at that time and is it possible to have contacted malaria in Vietnam and have it not appear till 16 months later? I never had malaria in Vietnam. Thank You, Paul