In this month’s case, we cover a classic high-risk medicolegal topic: chest pain. There has been extensive research on this topic in pursuit of identifying low-risk patients who can be discharged safely. This case occurred in 2011, so bear in mind that we have made significant strides over the past 10 years.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 01 – January 2022The Case

A 58-year-old woman presented to a small emergency department with chest pain. The patient and her husband lived in a different state and were visiting his parents. They were helping with some tasks around their house; she had been outside washing a Jeep. She had developed a slight sunburn on her back prior to noticing chest pain.

When she presented to the emergency department, the chest pain had been present for two to three hours. She described it at one point as a burning pain and at another point as a “raw” sensation. She had taken a Lortab with no improvement and also had vomited once.

In the emergency department, her vitals showed a blood pressure of 116/57, pulse of 94 bpm, respiratory rate of 24 per minute, temperature of 97.0 ºF, and an oxygen saturation of 90 percent on room air.

The physician did not have access to any previous medical records as this was her first time visiting this health system. However, he did note that she smoked a pack of cigarettes each day and had hypercholesterolemia, Crohn’s disease, hypothyroidism, and anxiety. The physical exam did not reveal any abnormalities.

The physician ordered an ECG, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, magnesium test, creatine kinase-MB, and troponin.

The patient was given nitroglycerin 0.4 mg sublingual, with no change in her pain. A 500-mL bolus of normal saline was given. After 30 mg of Toradol IV, she stated she felt “maybe a little better.”

The results of her tests showed a mild leukocytosis (14.4), slight hyperglycemia (118), and slight hypokalemia (3.3). The troponin was 0.06, within the normal limits of 0.0–0.10. The creatine kinase-MB was also normal. Her ECG was read as “normal sinus rhythm” by the physician.

The court documents had a poor copy of the ECG that would not appear well in print but is available for review at www.medmalreviewer.com/ekg.

The physician reasoned that the patient had a negative troponin, no ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction on ECG, and no relief of pain with nitroglycerin. The patient was discharged home.

The following morning, the patient was in the kitchen with her in-laws, making coffee. She suddenly collapsed and became unresponsive. They called 911. When EMS arrived, she was in ventricular fibrillation. She was defibrillated six times and finally had return of spontaneous circulation.

She was taken back to the same emergency department, arriving at 7:08 a.m. During the next 50 minutes, she lost pulses several times, and the physician caring for her placed her on a dopamine drip.

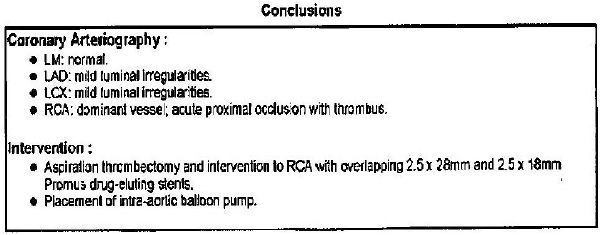

The process to transfer her to another facility started around 7:49 a.m. An EMS helicopter landed at 8:29 a.m. to whisk her to the receiving facility. During the flight, she briefly lost pulses, but return of spontaneous circulation was achieved again. By 9:04 a.m., she was in the catheterization lab at a university medical center. She was found to have a 100 percent occlusion of her right coronary artery, and a stent was placed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conclusions of the university catheterization lab.

Over the next day, she had increasing pressor requirements and additionally was determined to have a severe anoxic brain injury. Her hemodynamic condition continued to worsen, and as the family felt that continuing futile medical care was not in accordance with her wishes, she died within several minutes of switching to comfort-focused care.

The Lawsuit

The patient’s husband filed a lawsuit against the physician who discharged her. He sued the EMS service, alleging that dispatch took six minutes (as opposed to the policy of dispatch within two minutes). He sued both the EMT and paramedic who responded, claiming that they did not start CPR fast enough after arriving.

The allegations against the physician hinged on the fact that the patient had multiple risk factors for acute coronary syndrome and active chest pain and that only one troponin was obtained.

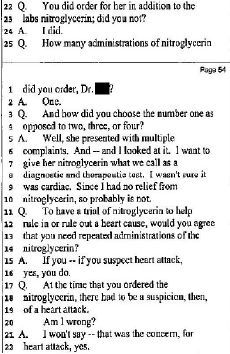

Figure 2: Excerpt from the physician defendant’s deposition.

The physician countered that her pain was burning, not heavy or pressure-like. He claimed that because it had been two to three hours since the pain started, only one troponin was necessary.

During the deposition, the plaintiff’s attorney focused on the patient’s response to receiving nitroglycerin. The doctor felt that since the patient did not have improvement of her pain, she was unlikely to have acute coronary syndrome (see Figure 2).

Ultimately, both sides agreed on a confidential settlement, and the lawsuit was withdrawn before it went to trial.

Discussion

This case illustrates why chest pain is such a high-risk area in emergency medicine. For many other complaints, a patient who is inappropriately discharged will have worsening symptoms over hours or days and have plenty of time to return to the emergency department and avoid catastrophe. Not so for chest pain. Sudden cardiac death leaves almost no opportunity for a second chance.

The development of the HEART Pathway decision aid and high-sensitivity troponins have significantly improved the care of chest pain patients since this case happened in 2011. This patient had a HEART score of 4 at a minimum (even with only giving her one point each for the history and ECG). This patient was not low-risk. Obtaining high-sensitivity troponins at arrival and two hours later likely would have revealed abnormalities that would have changed her care, although this is admittedly conjecture.

Ultimately, this case is a good reminder for emergency physicians to use the highly effective prognostic tools we have at our disposal. Not all major adverse cardiac events are avoidable, but appropriate application of these tools makes catastrophic outcomes very rare and provides an excellent defense when the unforeseeable happens.

Note: We do not yet have high-sensitivity troponins at my hospital. For a similar patient who presents with less than three hours of symptoms, we would perform three conventional troponins three hours apart (0h, 3h, 6h) prior to clearance for discharge from the emergency department.

To read the full medical record from this case, click here.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Chest-Pain Case Reminds Us of the Importance of Clinical Decision Tools”