Have you wondered when you’d start to routinely confront superbugs resistant to multiple antibiotics in your emergency department and not just in grocery line tabloids? Unfortunately, the time has come, and without awareness, some of our patients will have bad outcomes because of undertreatment.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 11 – November 2016The Wrong Drugs for a Superbug

In the September 2016 edition of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, my colleagues and I report on a 2013–2014 study of US emergency department patients presenting with acute pyelonephritis.1 A multiple-antibiotic-resistant E. coli that produces extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, referred to as ESBL, was the cause of as many as 8 percent of uncomplicated pyelonephritis cases and 17 percent of complicated pyelonephritis cases in some locations (see Figures 1 and 2). The study was done by EMERGEncy ID NET, an emergency department–based sentinel research network for emerging infections funded by the CDC since 1995, and involved 10 geographically diverse large university-affiliated US departments.

(click for larger image)

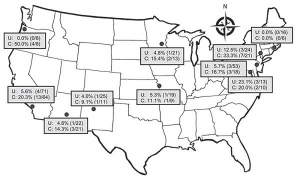

Figure 1. Prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli infection among emergency department patients with uncomplicated (U) and complicated (C) pyelonephritis by study site, United States, July 2013–December 2014. In vitro resistance to ciprofloxacin and/or levofloxacin is shown as % (number of patients with a resistant isolate/total

number of patients tested).

Source: CDC.

(click for larger image)

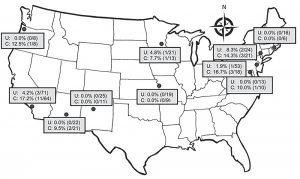

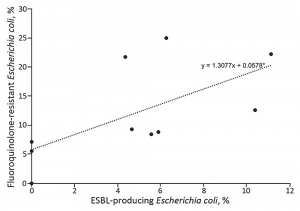

Figure 2. Prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli infections among patients with uncomplicated and complicated pyelonephritis by study site, United States, July 2013–December 2014. Each dot indicates a study site; the line to show the general trend between fluoroquinolone resistance and ESBL-producing E. coli was generated by using simple linear regression.

Source: CDC.

Importantly, we found that about three-quarters of patients with acute pyelonephritis due to ESBLs were empirically treated with antibiotics lacking in vitro activity—in other words, they were treated with the wrong drugs. This is a big problem. Treatment antibiotic in vitro activity discordance is associated with bad outcomes.

The FRQ/ESBL Connection

While you may not have noticed the emergence of ESBLs, you probably have seen more and more of your culture results showing E. coli resistant to our go-to pyelonephritis antibiotics, fluoroquinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin). Compared to when we studied this about a decade ago, overall rates of fluoroquinolone-resistant infections (FQR) increased from 4 percent to 12 percent. However, in some locations and among some patients with resistance risk factors and high-risk infections (ie, complicated infections, males, structural/functional urological conditions, antibiotic use, health care exposure, international travel within 90 days, or prior FQR or ESBL infection), FQR rates exceeded thresholds set by Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for which a different treatment strategy is recommended—FQR rates were above 10 percent and even 20 percent in some circumstances.2

At FQR rates of 10 to 20 percent, IDSA recommends a long-acting antibiotic of another class (eg, ceftriaxone or a single daily dose of an aminoglycoside) in addition to a fluoroquinolone. At FQR rates exceeding 20 percent, IDSA recommends abandoning fluoroquinolones, and this is where ESBLs come into play. Risk factors for ESBL infections were the same as for FQR. However, about one-third of patients with ESBL infections had no risk factors, indicating that ESBLs are now endemic in some US communities. This is becoming much like the situation seen in South America, India, Southeast Asia, and Southern Europe.

Note, however, that high FQR rates and emerging ESBLs are not yet a problem everywhere in the United States—so watch for increasing FQR rates. Your lab may or may not indicate an isolate is an ESBL strain. However, if it reports resistance to ceftriaxone, you can assume the bacteria are ESBL producers.

(click for larger image)

Figure 3. Prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli infections among patients with uncomplicated and complicated pyelonephritis by study site, United States, July 2013–December 2014. Each dot indicates a study site; the line to show the general trend between fluoroquinolone resistance and ESBL-producing E. coli was generated by using simple linear regression.

Source: CDC.

Locations with high FQR rates also have high ESBL rates (see Figure 3), so emergency physicians now need to know reliable empirical treatments for this emerged pathogen. ESBLs are resistant to all commonly used cephalosporins (eg, ceftriaxone) and frequently resistant to both fluoroquinolones and gentamicin. ESBLs are nearly universally susceptible to carbapenems, including long-acting ertapenem. The majority but not all isolates are susceptible to piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin. Some newer but less available agents (ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam) are very active against ESBLs.

Choosing the Right Drugs

The real question is, when do I pull the ESBL antibiotic trigger? Here is what I think is the best answer:

In settings with high FQR rates (above 15 percent), where ESBL-producing E. coli infections have emerged, and among persons with antimicrobial drug resistance risk factors—and especially for patients with or at risk for severe sepsis—you should consider empirical treatment with a carbapenem or another agent found to be consistently active based on the local antibiogram. Checking a patient’s past infections and understanding local resistance rates are key. If you’re lucky enough to have an ED pharmacist, having them track and report current resistance rates should be a priority. (You can expect updated IDSA guidelines soon.)

How about outpatient treatment? We’ve become good at treating-and-streeting many patients with acute pyelonephritis. However, at the present time, we have no oral antibiotics that are consistently active against ESBLs to treat an upper-tract (pyelonephritis) infection. This is where the superbug headlines have some justification.

If you endeavor to send a patient home and ESBLs are a concern, make sure to culture the urine, get the patient’s phone number, and start out with an ertapenem dose before discharge. Then there’s no perfect choice for oral antibiotics. Combining a beta-lactamase inhibitor drug, amoxicillin-clavulanate, with a third-generation cephalosporin, like cefdinir, may allow the latter to evade beta-lactamase destruction.3 Alternatively, you can go with a fluoroquinolone and hope since these antibiotics, when active, have the best clinical performance. Then be sure to give good discharge instructions and check the culture result in two days when you can contact the patient and make adjustments based on the susceptibilities.

Dr. Talan is professor of medicine in residence (emeritus) at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and chairman emeritus, department of emergency medicine, and faculty, division of infectious diseases, at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center in Sylmar, California.

References

- Talan DA, Takhar SS, Krishnadasan A, et al. Fluoroquinolone-resistant and extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infections in patients with pyelonephritis, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(9).

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-120.

- Prakash V, Lewis JS 2nd, Herrera ML, et al. Oral and parenteral therapeutic options for outpatient urinary infections caused by enterobacteriaceae producing CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(3):1278-1280.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Choosing Right Medication Critical to Combat Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Infections”