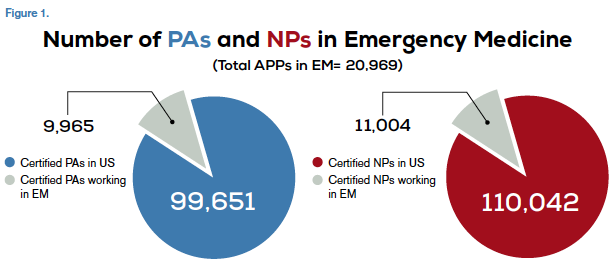

Lately, the topic of competency of advanced practice providers (APPs), also known as physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs), has come up frequently within hospitals and large health care organizations. These groups have been hiring more new APP graduates and want to know how long it will take for them to get up to speed within the institution. Additionally, it is a point of contention within emergency medicine, with some EM groups refusing to take new graduates until they demonstrate the necessary knowledge and skills—a Catch-22 if I’ve heard one. Don’t get me wrong! This is an important issue within a strongly procedure-based specialty in which clinical acumen must remain high. Emergency medicine is also a specialty among APPs that is highly sought (see Figure 1). Nonetheless, APPs seeking to work in emergency medicine must demonstrate they have advanced knowledge and experience in emergency medicine above and beyond that expected of entry-level APPs working in a generalist practice.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 02 – February 2015

Sources

http://www.aapa

http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-nurse-practitioners/>

http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/usworkforce/chartbook/chartbookpart1.pdf

Competence is defined not so much as “how long” but rather the achievement of the skill sets needed to practice in an ED. It is a narrow, specific question rather than a broad, philosophical one.

While there are a number of definitions of clinical competency, I prefer Norman’s definition of professional competence: “The habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served. Competence builds on a foundation of basic clinical skills, scientific knowledge, and moral development.”1

He goes on to say that competence has multiple functions: cognitive (using acquired knowledge to solve real-life problems), integrative (using biomedical and psychosocial data in clinical reasoning), relational (communicating effectively with patients and colleagues), and affective/moral (the willingness, patience, and emotional awareness to use these skills judiciously and humanely). I was struck by a final comment that competence is “developmental, impermanent, and context-dependent.”1 Competence is certainly developmental in the context of lifelong learning. If it is indeed impermanent (temporary, transient, transitory, passing, fleeting), then it must be evaluated frequently. There is no argument that it is context-dependent, whether by level of care, specialty knowledge required, or institution.

Clearly, competence is complex. While the PA and NP professions have developed and published a list of specific skills necessary to be considered competent, which mirror and parallel those of our physician colleagues, the question becomes, “How do we actually demonstrate them?”

Benner developed one of the best-known competency definitions in 1982 with her novice-to-expert model, which applied the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to nursing. It has been widely used as a tool to determine expertise.4,5 Her model describes the five levels of expertise as:

- Novice: A beginner with little to no experience. Novices face the inability to use discretionary judgment and require significant supervision.

- Advanced beginner: Able to demonstrate marginally acceptable performance based on some real-life experience.

- Competent: Has usually been on the job for two to three years. At this level, the clinician has a sense of mastery and the ability to cope with and manage many aspects of patient care.

- Proficient: Able to grasp clinical solutions quicker and able to home in on accurate regions of the problem faster.

- Expert: No longer relies on analytics to connect to understanding of the problem but has an intuitive grasp and is able to zero in on the all aspects of the problem at hand without any wasteful or unfruitful possibilities.5

Benner maintains that knowledge accrues over time in clinical practice and is developed through dialogue in relationship and situational contexts.6 It should be noted that clinical experience is not the mere passage of time or longevity within a clinical experience but rather the actual level of clinical interaction. The clinician, therefore, may move forward or backward in the model, depending on the situation.

In the Benner model, the novices and advanced beginners would be prematriculants and students. You can see variations of this learning curve in different situations, whether it is a new clinician in the ED or an experienced clinician moving to a new practice.

Returning to the comment that prompted this article: when is an APP fully competent to see patients? There has been some good research in the last decade that demonstrates APPs have excellent patient care outcomes, even when taking into account the particular clinician level (novice through expert). The reality is that competence is acquired gradually, and even when APPs are far from fully competent, they can still see patients as long as the supervision is commensurate with the need.

A seasoned APP with emergency medicine experience will be more likely to hit the ground running, may work at a more rapid pace than a new graduate, and may be able to handle a higher volume of patients.

This is a challenging topic because what we do requires factual knowledge and the consistent, appropriate application of that knowledge. We know how to measure factual knowledge, more or less, but assuredly we don’t know how to measure the latter (possibly the most important part). In my opinion, we need a pragmatic approach to determine whether a clinician is competent and continues to be so.

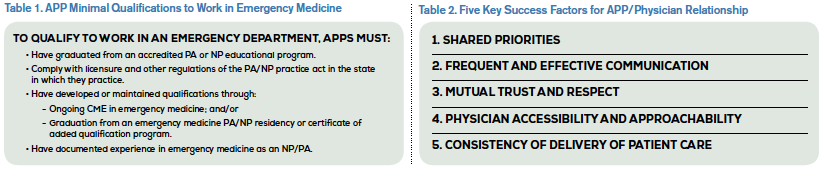

When recruiting an APP, an emergency department should consider its needs and match the expectations of the ED and the APP. Another aspect to consider is the level of experience (see Table 1). Any hospital or emergency medicine group hiring a new graduate should be mindful that a newly trained APP requires more mentoring and closer collaboration than an experienced APP. A seasoned APP with emergency medicine experience will be more likely to hit the ground running, may work at a more rapid pace than a new graduate, and may be able to handle a higher volume of patients.

The next question is how to gauge ongoing competence. One method is to do a 360 survey. Such feedback can be a powerful tool for competency evaluation in a rapidly changing and often bewildering emergency medicine clinical environment. Of course, these tools must be used appropriately and intelligently in order to be effective. Here’s how it might work: All coworkers of a particular clinician would be surveyed on the perceived elements of clinical competence, including knowledge, application of knowledge, efficiency, ability to make decisions, and attitude toward patients. Every person in the emergency department could anonymously complete the survey. This would include nurses, techs, other APPs, housekeeping, on-call members of the medical staff—literally everybody, although not all of them will be capable of making some of these determinations. Then the ED director would let the clinician review and discuss the feedback. Everyone in the department would know they would be similarly evaluated.7 This is the most brutal, yet fair and efficient, way to assess competency in its broadest sense. Will all of the opinions be factually substantiated? No! What better technique do we have, at least for now?

But wait! Perhaps competence is not the endgame. Perhaps competence is really a minimum standard. Competence, albeit novice if we use the Benner model, is measured by completion of the PA or NP curricula (meeting the course objectives) and passage of board/licensure exams, just as physician competence is, essentially.

Most, if not all, would agree that mastery is achieved by the acquisition of additional knowledge (certificate of added qualifications, advanced certification) coupled with sound practice and experience. Mastery or expertise, some say, is what we should focus on, the achievement of which is quite individual. All clinicians can move toward mastery, but not all will actually achieve it. I suggest that competency is the starting point and mastery (expertise) is achieved by the ongoing commitment to expand clinical knowledge—keeping up with the literature, completing CME programs, learning from fellow clinicians—coupled with an extensive clinical experience in which knowledge is clinically applied with the achievement of the best results feasible within the constraints of the individual patient encounter.8

Lastly, once should not determine competency or mastery in a vacuum. Medicine is a team effort, and in the case of an APP, the interaction with the collaborating physician is essential. Table 2 demonstrates the factors needed to achieve success in the APP/physician relationship.9

A successful APP/physician team requires trust, communication, current evidence-based practice guidelines, feedback, and experience. Although state laws vary regarding the extent of practice and level of collaboration for APPs, hospitals and ED groups may set their own standards independently.

The goal is, of course, collaboration among competent APPs, physicians, and other health care providers working together to meet the needs of patients and improving patients’ health and outcomes in the emergency department setting.

Dr. Danielsen is professor and dean of the Arizona School of Health Sciences, a school of A.T. Still University, in Mesa. He has practiced for more than 40 years in the fields of emergency medicine, occupational medicine, internal medicine, and allergy/asthma. He is a faculty member with The Center for Medical Education, Inc., lecturing at the Emergency Medicine Boot Camp.

Dr. Danielsen is professor and dean of the Arizona School of Health Sciences, a school of A.T. Still University, in Mesa. He has practiced for more than 40 years in the fields of emergency medicine, occupational medicine, internal medicine, and allergy/asthma. He is a faculty member with The Center for Medical Education, Inc., lecturing at the Emergency Medicine Boot Camp.

References

- Norman GR. Defining competence: a methodological review. In: Neufeld VR, Norman GR, eds. Assessing Clinical Competence. New York, N.Y.: Springer; 1985:15-35.

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65:s63-s67.

- Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, et al. Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet. 2001;357:945-949.

- Gentile DL. Applying the novice-to-expert model to infusion nursing. J Infus Nurs. 2012;35:101-107.

- Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82:402-407.

- Brykczynski KA. Patricia Benner: Caring, clinical wisdom, and ethics in nursing practice. In: Alligood MR, ed. Nursing Theorists and Their Work. 8th ed. St Louis, Mo: Elsevier; 2014:120-146.

- Lepsinger R, Luca AD. The Art and Science of 360-Degree Feedback. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

- Danielsen RD. The complexities of competency. Clinician Reviews. 2014;24(12):6-8.

- Danielsen R, Ballweg R, Vorvick L, et al. The Preceptor’s Handbook for Supervising Physician Assistants, Chapter 16. Common Sense Supervision. Jones & Bartlett LEARNING: 2012.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Competency Measurement Approach for Advanced Practice Providers in Emergency Medicine”

February 16, 2015

Gerry KeenanA timely explanation!We can only hope it guides reasoned decision making.