Pulmonary embolism (PE) in pregnancy is quite uncommon, estimated to occur in 0.02–0.1 percent of pregnancies and accounting for approximately 0.02 percent of pregnancy-related hospitalizations.1–3 Historically, the evaluation of pregnant patients for potential PE has been challenging. Signs and symptoms of PE can be nonspecific and may overlap with normal symptoms of pregnancy. Although we have several validated risk stratification tools for use in nonpregnant patients—such as the Wells Score, the PE Rule Out Criteria (PERC), the age-adjusted D-dimer threshold and, more recently, risk-adjusted D-dimer approaches such as the YEARS algorithm—these tools remained largely untested in pregnant patients. A 2017 review of international guidelines found that none recommended the use of risk stratification tools in pregnant patients.4

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 05 – May 2022Further, the use of the D-dimer in pregnant patients has been controversial. It is well-established that D-dimer levels increase throughout normal pregnancies such that by the third trimester few, if any, individuals have a D-dimer below standard thresholds.5,6 While trimester-adjusted D-dimer thresholds have been recommended by some experts, these cutoffs have not yet undergone validation.7 Others have argued that a D-dimer is not sensitive enough in pregnancy. For example, the DiPEP study reported that the D-dimer had a sensitivity of 88.4 percent. In that study, however, more than 70 percent of patients received anticoagulation with a low-molecular-weight heparin prior to the D-dimer, which could contribute to false-negative results.8,9 Additionally, the administration of anticoagulation prior to the diagnosis of PE is not standard practice in the United States for patients appropriate for D-dimer testing (ie, at low to intermediate risk of PE).

Given these limitations to risk-stratifying patients with potential PE, CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) and ventilation-perfusion scans (V/Q scans) have been the only way of excluding PE. While both of these imaging modalities are safe in pregnancy, they impart ionizing radiation to both the pregnant individual and the fetus. Further, both imaging modalities are imperfect in pregnancy and may yield indeterminate results.

The Good News

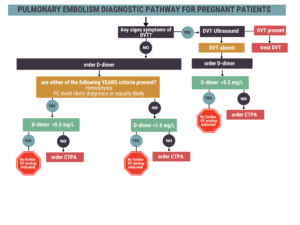

Figure 1 (click to enlarge): This algorithm allows more pregnant individuals to avoid imaging compared to the algorithm using the RGS, likely due to the elevated D-dimer threshold.

Over the past few years, recent studies have provided evidence that many pregnant patients can be risk-stratified and have PE excluded without the need for imaging. A 2018 study by Righini and colleagues found that an algorithm combining the Revised Geneva Score (RGS), lower-extremity ultrasound, computed tomographic pulmonary angiogram and/or V/Q scan, and D-dimer resulted in no missed cases of symptomatic venous thromboembolism at three months. Meanwhile, imaging was avoided in 11.6 percent of the 367 cases.10

At nearly the same time, the developers of the YEARS algorithm published an assessment of the algorithm’s performance in pregnant patients and found even more favorable results than the use of the Righini algorithm. The YEARS algorithm, an internationally validated risk-adjusted approach to the D-dimer, allows a D-dimer threshold of 1,000 ng/mL in patients who have no signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), have no hemoptysis and in whom PE is not the most likely diagnosis.11–13 In a prospective study of 498 pregnant patients in which the YEARS algorithm and lower-extremity ultrasound were used, only one patient in whom PE was initially excluded was diagnosed with DVT at three-month follow-up. No patients were diagnosed with PE during the follow-up period. In addition, the YEARS algorithm allowed exclusion of PE without imaging in 65 percent of patients enrolled in the first trimester, 46 percent in the second trimester, and 32 percent in the third trimester.14 Researchers also retrospectively evaluated the performance of the pregnancy-adapted YEARS algorithm in the Righini et al cohort and found that it was safe and would have resulted in fewer imaging studies than the RGS algorithm.15

In fact, the use of the D-dimer and the YEARS algorithm have begun to appear in professional society guidelines. Previous iterations of guidelines varied in their recommendations to use a D-dimer, with five of seven guidelines recommending against the use of the D-dimer.16 These guidelines, however, lacked quality prospective studies to support these recommendations. The most recent European Society of Cardiology guideline for the diagnosis of PE recommends the use of the D-dimer in conjunction with clinical prediction rules in pregnancy (level IIa recommendation—the weight of evidence is in favor of efficacy).17 A 2021 meta-analysis of four studies supports this, reporting a sensitivity of a negative D-dimer in pregnancy of 99.5 percent (95% CI, 95.0–100%).18 Other professional society guidelines have not yet been updated after the publication of these studies.

Potential Pitfalls

There are some potential pitfalls with this approach. First, the YEARS algorithm depends on the D-dimer assay, which has poor specificity, particularly in pregnancy. Thus, as in any population, a D-dimer should not be ordered indiscriminately and should be limited to those who would otherwise be destined for imaging due to suspicion for PE. Second, these studies did not compare performance of structured risk stratification with clinical gestalt. Although possible, it’s unlikely that in the United States practice milieu clinical gestalt would result in fewer imaging studies than these algorithms. Third, few pregnant patients evaluated for PE in these studies actually had a PE—4 to 7 percent. This suggests that even with risk stratification and adjusted D-dimer thresholds, we likely overtest for PE in pregnant patients.

The Algorithm

The pregnancy-adapted YEARS algorithm can be pictured in Figure 1. This algorithm allows more pregnant individuals to avoid imaging compared to the algorithm using the RGS, likely due to the elevated D-dimer threshold.

Overall, new data indicate it’s time to stop routinely imaging pregnant patients with suspected PE. Rather, structured risk stratification with a pregnancy-adapted YEARS approach, including a negative risk-adjusted D-dimer result, can safely exclude PE in pregnant patients without the need for imaging.

References

- Elgendy IY, Gad MM, Mansoor H, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism during pregnancy and puerperium: national trends and in-hospital outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(8):2102-2113.

- Lee MY, Kim MY, Han JY, et al. Pregnancy-associated pulmonary embolism during the peripartum period: an 8-year experience at a single center. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57(4):260-265.

- Jacobsen AF, Skjeldestad FE, Sandset PM. Incidence and risk patterns of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and puerperium—a register-based case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):233.e1-e7.

- Wan T, Skeith L, Karovitch A, et al. Guidance for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism during pregnancy: consensus and controversies. Thromb Res. 2017;157:23-28.

- Kline JA, Williams GW, Hernandez-Nino J. D-dimer concentrations in normal pregnancy: new dignostic thresholds are need. Clin Chem. 2005;51(5):825-829.

- Murphy N, Broadhurst DI, Khashan AS, et al. Gestation-specific D-dimer reference ranges: a cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2015;122(3):395400.

- Kline JA, Kabrhel C. Emergency evaluation for pulmonary embolism, part 2: diagnostic approach. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(1):104-117.

- Goodacre S, Horspool K, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. The DiPEP study: an observational study of the diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment, D-dimer and chest x-ray for suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy and postpartum. BJOG. 2019;126(3):383-392.

- Goodacre S, Nelson-Piercy C, Hunt BJ, et al. Accuracy of PE rule-out strategies in pregnancy: secondary analysis of the DiPEP study prospective cohort. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(7):423-428.

- Righini M, Robert-Ebadi H, Elias A, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism during pregnancy: a multicenter prospective management outcome study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(11):766-773.

- van der Hulle T, Cheung WY, Kooij S, et al. Simplified diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism (the YEARS study): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):289-297.

- Kabrhel C, Van Hylckama Vlieg A, Muzikanski A, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the YEARS criteria in emergency department patients evaluated for pulmonary embolism. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(9):987-994.

- Freund Y, Chauvin A, Jimenez S, et al. Effect of a diagnostic strategy using an elevated and age-adjusted D-dimer threshold on thromboembolic events in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(21):2141-2149.

- van der Pol LM, Tromeur C, Bistervels IM, et al. Pregnancy-adapted YEARS algorithm for diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(12):1139-1149.

- Langlois E, Cusson‐Dufour C, Moumneh T, et al. Could the YEARS algorithm be used to exclude PE during pregnancy? Data from the CT‐PE‐pregnancy study. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(8):1329-1334.

- Cohen SL, Feizullayeva C, McCandlish JA, et al. Review comparison of international societal guidelines for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism during pregnancy. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(3):e247-e258.

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of actue pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1901647.

- Bellesini M, Robert‐Ebadi H, Combescure C, et al. D‐dimer to rule out venous thromboembolism during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(10):2454-2467.

Dr. Westafer (@LWestafer) is assistant professor of emergency medicine and emergency medicine research fellowship director at the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate and co-host of FOAMcast.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Decoding Pulmonary Embolism Evaluation in Pregnancy”