Explore This Issue

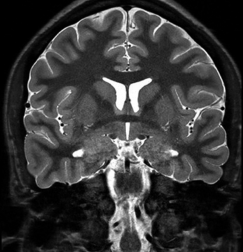

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 06 – June 2019A T2 coronal MRI of a patient with limbic encephalitis, displaying right amygdala enlargement and hyperintensity.

Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135(1):134-141. Reprinted with permission.

A few years ago, a best-selling autobiographical work, Brain on Fire, chronicled one of the first instances of diagnosis for N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) encephalitis. The story depicted by the author is one of a young woman’s descent into madness caused by encephalitis before its relatively novel cause is determined by a New York neurologist.1 The book details her recovery, and the story has even been developed into a feature film on Netflix.

In historical times, such cases may have been responsible for reported incidents of “demonic possession.” In 2009, when the events of Brain on Fire transpired, this diagnosis remained obscure. Now, in 2019, this diagnosis, under the umbrella classification of autoantibody-mediated encephalitis, is prominently featured in the educational series of one of the largest critical care conferences in the world.2 The past decade has seen both a heightened recognition of these syndromes and also the necessary laboratory advancements required for diagnosis. This related collection of syndromes is almost certainly more common than any of us were aware during our medical education, and it is important to recognize them because early immunotherapy can profoundly improve recovery.

Unfortunately, recognizing the conditions or performing diagnostic testing for these syndromes isn’t terribly straightforward.3 The overlap between autoantibody-mediated encephalitis and more common clinical syndromes such as delirium, dementia, and substance abuse–related psychosis is substantial. The most prudent consideration for these diagnoses would be in a specific subset of patients with altered mental status for whom another clinical diagnosis is not fully supported by all manifested symptoms and testing hasn’t identified a cause. Some of the clinical features most commonly seen in combination for autoantibody-mediated encephalitis include:

- Acute or subacute onset of cognitive impairment and/or memory loss

- New-onset seizures or status epilepticus

- Acute psychiatric illness, including psychosis, with rapid progression

- Unusual movement disorders

- Autonomic dysfunction, hyperexcitability, or insomnia

The type of autoantibody-mediated encephalitis featured in Brain on Fire was limbic encephalitis, of which antibodies against the NMDA receptor are but one culprit. The phenotype expressed by limbic involvement skews toward the cognitive and psychiatric spectrum, followed by seizures. Antibodies against the NMDA receptor are the most common, followed by antibodies against leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1 and contactin-associated protein 2, components of voltage-gated potassium channel complexes.4 Interestingly, many of these autoantibody-mediated syndromes have paraneoplastic associations. Almost 40 percent of antibodies against the NMDA receptor are associated with ovarian teratomas, making this association a potential red flag for limbic encephalitis in the appropriate clinical context.

The brainstem encephalitides are likewise included in the spectrum of autoantibody-mediated disease. These syndromes typically display features associated with abnormal eye movements and inflammation of the cranial nerves. The most prominent and common of these syndromes includes the neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, characterized by anti-aquaporin-4 or anti-ganglioside GQ1b antibodies. The latter antibody has been found to be the causative etiology for Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis, which was described more than half a century ago and typically includes ataxia and ophthalmoparesis in the context of altered consciousness.

Once alternative diagnoses have been fully and appropriately evaluated, most proposed diagnostic strategies for the autoantibody-mediated encephalitides include neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) evaluation as critical to identifying the diagnosis.5 Several subtypes of encephalitis include specific abnormal findings on magnetic resonance imaging, while CSF pleocytosis or the presence of oligoclonal bands raises suspicion for central nervous system inflammation. Commercial assays for CSF antibody detection are available, and specialist consultation can help determine the most appropriate tests to order for a specific phenotype. Finally, electroencephalogram may be a useful diagnostic modality but has variable positive and negative likelihood ratios for different subtypes of autoantibody-mediated encephalitis.

The immediate care for these patients is typically undertaken without the results of antibody tests, as the turnaround time is, at best, several days. Treatment options include high-dose corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, or a combination, all in consultation with a specialist. As many of these syndromes are precipitated by, or associated with, malignancy, appropriate imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis may further inform the diagnosis. Small-cell lung cancers are most frequently implicated, along with thymomas, breast cancer, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Patients presenting to facilities without access to such specialty care may benefit from transfer to a tertiary center.

Of course, the first step in diagnosing any of these syndromes is inclusion in the differential diagnosis. There are differing opinions regarding the incidence of these diagnoses, with proponents reporting that, particularly in the young, the frequency may exceed that of the infectious encephalitides.6 However, even considering such elevated frequency, the approximate incidence is still only one per 100,000 person-years. A mid-sized city might see 10 cases of autoimmune encephalitis per year, meaning the frequency of an individual emergency physician encountering this diagnosis might be once per decade. Therefore, while awareness of this condition is important, caution should be exercised to avoid overtesting as a result of availability bias (believing something is more common than it actually is simply because we are more aware of it).

At the very least, no need to call an exorcist!

References

- Cahalan S. Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2012.

- Carr D. Turning a zebra into a horse. Presented at: Social Media and Critical Care Conference, March 2019; Sydney, Australia.

- Jammoul A, Li Y, Rae-Grant A. Autoantibody-mediated encephalitis: not just paraneoplastic, not just limbic, and not untreatable. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(1):43-53.

- Binks SNM, Klein CJ, Waters P, et al. LGI1, CASPR2 and related antibodies: a molecular evolution of the phenotypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(5):526-534.

- Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):391-404.

- Dubey D, Pittock SJ, Kelly CR, et al. Autoimmune encephalitis epidemiology and a comparison to infectious encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(1):166-177.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “Demonic Possession or Autoantibody-Mediated Encephalitis?”

May 25, 2020

JuliaFascinating. Could seemingly demonic possession be attributed to any subtype of encephalitis or does it generally relate to Seronegative Limbic Encephalitis, Non-Paraneoplastic Limbic Encephalitis, and Typical/Atypical Limbic Encephalitis?

May 28, 2020

Ryan RadeckiTo my knowledge, it pertains specifically to these NMDA receptor antibodies – and produces the clinical syndromes associated with other hallucinogenic pharmacology (e.g., Ibotenic acid in Amanita mushrooms).