Emergency medicine training prepares us well for managing acute events in our patients’ lives. In fact, combined improvements in public health and general health care integration have resulted in major shifts in how patients live and die in the United States. Many years ago, infection and trauma claimed lives quickly, and life expectancies were short. Now, medical and surgical advancements have transformed health care, benefitting most of us with longer lives.1

Although many seniors still enjoy a high quality of life, the individuals we meet in the emergency department are generally not so lucky. Individuals with cardiopulmonary disease, cancer, neurologic failure (dementia, stroke, or combined syndromes), and their related complications have become the predominant populations in many EDs.1

Additionally, there are just more seniors. Since 2013, and predicted through 2019, more than 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day. In 2010, the US Census Bureau reported more than 40 million citizens were 65 and older. By 2050, those number of those patients is projected to double to more than 85 million. Although the full impact of our country’s aging population on health care is not yet known, we do know the incidence of advanced chronic illness is already on the rise.1

As this population increases, how do we navigate clinical challenges these patients pose? How should we answer when worried caregivers ask us, “Why does she keep ending up in the hospital? What comes next?”

Illness Trajectory

Illness trajectories are general paths that chronic conditions usually take.2–4 These trajectories give insight into prognosis and the likelihood of significant recovery. By discussing these paths with patients, we empower them with information about their clinical course. This shared understanding fosters appropriate health care decision making that aligns with the clinical picture.

By understanding the path these conditions take, emergency physicians can potentially advance the dialogue from fixing the unfixable to caring for a loved one at the end of life.2

The cardiopulmonary trajectory (see Figure 1) is one of the most well-known to ED providers because severe exacerbations are common and dramatic. Areas helpful to recognize on this trajectory are patients’ long-standing functional limitations and their decreasing physiologic reserve. These patients and families often have difficulty recognizing the severity of their illnesses because they have survived hospitalizations before. As exacerbations occur at closer intervals, families may describe the sensation of being trapped in a cycle between rehabilitation or nursing home and subsequent hospitalizations. It is helpful to note that, while they may get close, patients generally do not return to their baseline after a hospitalization and progress on a course of general decline.3,4

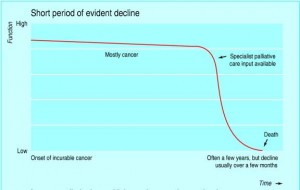

Cancer has a different trajectory than cardiopulmonary disease (see Figure 2). Cancer patients who were fairly healthy before an early-stage diagnosis often continue to do well through their treatments and hopefully progress to a cure. People can return to baseline if they only require symptomatic treatment for simple challenges like chemotherapy-induced dehydration or nausea and vomiting. However, if prolonged immunocompromise or significant metastatic spread occurs, patients eventually reach a physiologic tipping point. When this happens, decline is usually rapid, and patients will not revert back to their previous quality of life.3,4

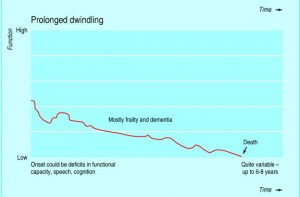

Neurologic failure may be related to dementia or other irreversible and progressive neurologic conditions (see Figure 3). Stroke may also cause neurologic failure if either a massive stroke is survived or is superimposed on another progressive neurologic condition, leading to acceleration of a patient’s functional decline. These patients live with low levels of functional and physiologic reserve. Opportunistic infections (eg, urine, respiratory) or minor falls lead to disproportionate levels of morbidity and mortality. Neurologic failure most often progresses to the constellation of bedbound status, opportunistic infection, dysphasia, weight loss, and death. During decline, families and caregivers may become confused because patients have “good days and bad days.” Despite these minor fluctuations, established neurologic failure is terminal and not reversible. 2,3

Putting Trajectories Into Practice

Although it may seem difficult to move beyond the acute exacerbation during a long shift, emergency physicians can begin discussions of these trajectories and what they may mean for our patients and their caregivers. Sharing disease trajectory information empowers providers and the patients we treat to make the best decisions possible, whether moving forward with a procedure or a consultation for palliative care.1 (See sidebar for a sample conversation.)

The ED is increasingly being called upon to help hospitals and health systems deal with our nation’s growing population of patients with advanced chronic illness. Emergency physicians will continue to advocate and develop new best practices for our most frail and vulnerable patients. By understanding disease trajectory pathways and discussing them with our patients, we can positively influence a patient or family to make appropriate medical decisions.1–3

References

- Lamba S, Nagurka R, Murano T, et al. Early identification of dying trajectories in emergency department patients: potential impact on hospital care. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:392-395.

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289:2387-2392.

- Murray S, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. 2005;330:1007-1011.

- West L, Cole S, Goodkind D, et al. 65+ in the United States: 2010, current population reports. US Census Bureau Web site. Available at: census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p23-212.pdf. Accessed Oct. 16 2015.

The authors are members of the ACEP Palliative Medicine Section. Dr. Aberger is core faculty in emergency medicine and palliative medicine at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey. Dr. Fetzer is an emergency medicine attending physician at Advocate Health Care and director of palliative care at Rainbow Hospice and Palliative Care in Mount Prospect and Park Ridge, Illinois. Dr. Goett is assistant professor and assistant director for advanced illness and bioethics in the departments of emergency medicine and palliative care at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark. Dr. Lamba is associate professor of of emergency medicine and associate dean of medical education at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. Dr. Rosenberg is chairman of emergency medicine at St. Joseph’s Healthcare System and associate professor of clinical emergency medicine at New York Medical College.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Disease Trajectory as an Emergency Medicine Tool”