The Case

A 28-year-old female presents with severe lower right quadrant pain. Her intermittent pain started three days ago. She has had several episodes of non-bloody emesis, which usually occurs when the pain worsens, but she denies vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, urinary symptoms, fever, diarrhea, back pain, or other symptoms. She is significantly tender in the right lower quadrant, but a pelvic exam is unrevealing.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 06 – June 2020Abdominal and pelvic pain are common presentations in the emergency department, ranging from benign to serious. One important and dangerous condition not to miss is ovarian torsion.

Ovarian torsion occurs when the ovary completely or partially rotates on the ligamentous supports, resulting in necrosis and infertility if missed.1–5 Here are five myths that can mislead the emergency physician.

Myth #1: Only Women of Reproductive Age Experience Ovarian Torsion

While ovarian torsion most commonly affects women of reproductive age, typically around 30 years old, the risk factor most strongly associated with torsion is an adnexal mass >5 cm, occurring in up to 80 percent of patients with torsion; underlying risks include polycystic ovarian syndrome, undergoing fertility therapies, history of previous torsion, and history of tubal ligation.3–16

Approximately 15 percent of ovarian torsion cases occur in pediatric patients, which is thought to occur due to an elongated utero-ovarian ligament.3–5,11–13 Unlike other patient populations, more than half of pediatric patients with ovarian torsion have normal ovaries.3–5,9–16 Postmenopausal patients account for another 15 percent of cases, although almost all of these patients have an enlarged ovary or mass within the pelvis. Pregnant patients are also at risk, accounting for 10 to 25 percent of all cases.5,9,16–20 In fact, pregnancy is a significant risk factor for torsion, primarily due to progesterone increasing the risk of ovarian cyst formation.16–20 Most patients with torsion during pregnancy experience it in the first 17 weeks (81 percent), and 73 percent of these patients have undergone fertility therapy.4,18–20 Fertility treatments can result in ovarian hyperstimulation, further increasing the risk of ovarian cyst formation.5,15

Key Point: Consider ovarian torsion in female patients of all ages.

Myth #2: All Patients with Ovarian Torsion Present with Acute Severe Pain and Vomiting

Symptoms of ovarian torsion occur due to occlusion of vascular flow from torsion of the vascular pedicle. We classically associate this with abrupt, severe pain in the lower abdomen that radiates to the flank or inguinal area as well as nausea and vomiting.4–7,10,21,22 However, sudden, severe pain only occurs in 50 percent of patients.4–7,22 Some form of pain is present in up to 90 percent of patients, but the description of the pain varies.4–7,22 Symptoms can be vague, lasting for days to months, and be constant or episodic due to intermittent torsion and detorsion of the ovary.23,24 Pain may resemble that of appendicitis, urolithiasis, ectopic pregnancy, and other conditions. Nausea and vomiting occurs in up to 70 percent of patients, and fever may also occur in 2 to 20 percent of patients, further complicating the diagnosis.4,6,7,12,23,24 Diagnosing torsion in infants is extremely difficult, as these patients may present with irritability, fussiness, vomiting, or feeding intolerance.5,11–13 Pediatric females can present with diffuse pain and fever, typically resulting in delayed diagnosis.5,25,26

Importantly, the critical ischemia time for the ovaries that results in necrosis is unknown. Patients may have symptoms for hours to days, and there is no specific time cutoff that reliably predicts irreversible necrosis.4,5,27–29

Key Point: Patients with ovarian torsion may present with constant, severe, abrupt, intermittent, or mild pain.

Myth #3: A Normal Physical Exam, Including Pelvic Exam, Can Rule Out Torsion

Up to one-third of patients have no tenderness on either an abdominal or pelvic exam.4–7,10 One of the key risk factors is an ovarian mass or cyst, but unfortunately, exams are also unreliable in detecting the presence of adnexal tenderness or mass, with an inter-examiner reliability ranging from 23 to 32 percent.5,30 Results are no better with a gynecologist-performed exam, with a sensitivity of detecting a mass >5 cm of 15 to 36 percent.5,31 The exam’s reliability further decreases in the setting of increased patient weight (defined as >200 pounds) and in patients older than age 55.32

Key Point: A normal abdominal or pelvic exam does not exclude ovarian torsion.

Myth #4: A Normal Ultrasound Can Rule Out Torsion

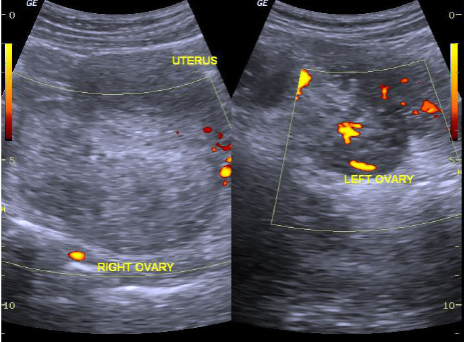

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) with grayscale imaging and Doppler flow is usually the go-to imaging modality to evaluate for torsion. While TVUS has high specificity, it has poor sensitivity, ranging from 35 to 85 percent.33–35 The most common finding is an enlarged ovary due to edema, often with a mass.5,16,17,33–36 Other signs include an ovary displaced to the midline. The “string-of-pearls sign,” in which an enlarged ovary is lined around the periphery by follicles, suggests torsion.5,16,17,33–36 Grayscale may demonstrate a hypoechoic appearance of the ovary due to edema. Color Doppler may reveal decreased or absent intraovarian venous flow, which may be followed by absent arterial flow later in the disease (see Figure 1).5,16,17,33–36 One major pitfall with TVUS use is reliance of normal arterial flow to exclude torsion, as the ovaries have dual blood flow from the ovarian and uterine arteries.5,34 Torsion initially occurs with lymphatic and venous outflow obstruction. Arterial inflow is not compromised until later in the disease course.35,36 Arterial flow is completely normal in more than 25 percent of patients with surgery-confirmed torsion, and more than half of patients will have detectable arterial flow.16,17,35,36 Therefore, assessing venous flow is a better indicator. However, intermittent or partial torsion may also result in normal venous flow TVUS.

Figure 1 (ABOVE)

Ovarian torsion on ultrasound with enlarged ovary and absent vascular flow.

Case courtesy of Dr. Maulik S. Patel, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 30458

Literature suggests that combining ultrasound findings can improve sensitivity and specificity compared to only focusing on vascular flow.5 Evaluating for free fluid within the pelvis, ovarian enlargement and edema, and vascular flow can improve sensitivity.5 The whirlpool sign is strongly suggestive of torsion; it consists of a circular collection of blood vessels within an enlarged ovary or mass.5,37,38

Key Point: Do not rely on normal vascular flow to rule out ovarian torsion. A combination of TVUS findings such as ovarian enlargement and mass, free fluid in the pelvis, and vascular flow may improve your ability to diagnose ovarian torsion.

Myth #5: CT of the Abdomen and Pelvis Has No Role in Evaluating Ovarian Torsion

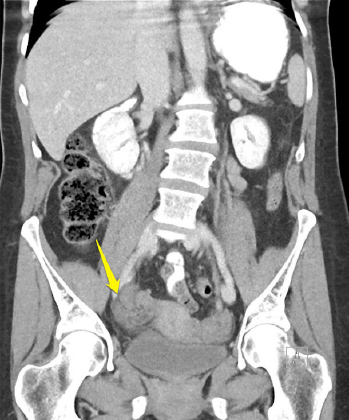

Figure 2 (RIGHT)

CT depicting twisted follicle and enlarged ovary.

Patients with undifferentiated abdominal pain often undergo CT, but can CT assist in ruling in or out ovarian torsion? CT with IV contrast will often display findings suggestive of torsion.5,16,33,39–42 Findings on CT with high specificity for ovarian torsion include a twisted vascular pedicle (see Figure 2), a thickened fallopian tube with target/beak-like appearance, absent or reduced ovarian enhancement with contrast, and an enlarged ovary with a follicular ovarian stroma and peripherally displaced follicles.16,33,39–42 Features that are commonly found but not specific include an enlarged ovary, an adnexal mass, adnexal mass mural thickening, free pelvic fluid, fat stranding surrounding the ovary, uterine deviation toward the torsed ovary, and ovarian displacement toward the uterus.16,33,39–42 CT with contrast demonstrates a high sensitivity for these secondary findings, approaching 100 percent.16,33,39–42 If one of these secondary findings is present, TVUS and OB/GYN consultation should be expedited. If these findings are not present and the ovary is normal in size, TVUS may not be needed, depending on the any changes in the clinical course. If the ovary is abnormal on CT, then obtain TVUS.

Finally, if suspicious of torsion based on your history and exam, an ob-gyn consultation should be initiated prior to imaging. If an ob-gyn is unavailable, a general surgery consultation is warranted. Torsion is a time-sensitive condition; early involvement of specialists is paramount.

Key Point: A normal CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast that has no secondary findings displays high sensitivity for excluding ovarian torsion. If secondary findings such as an enlarged ovary are present, then obtain TVUS.

Case Conclusion

The CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveals a normal appendix but an enlarged right ovary. A small amount of pelvic free fluid and fat stranding around the right ovary are observed. You consult the ob-gyn on call, who requests a TVUS. The TVUS reveals an enlarged ovary with decreased venous flow on Doppler. The ob-gyn evaluates the patient and takes her to the operating room, where detorsion is successful.

Dr. Long is an emergency physician in the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Dr. Koyfman (@EMHighAK) is assistant professor of emergency medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center and an attending physician at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. Dr. Gottlieb is associate professor, ultrasound division director, and ultrasound fellowship director in the department of emergency medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

References

- Oelsner G, Shashar D. Adnexal torsion. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(3):459-463.

- Hibbard LT. Adnexal torsion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152(4):456-461.

- Adelman S, Benson CD, Hertzler JH. Surgical lesions of the ovary in infancy and childhood. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;141:219-226.

- Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: a fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(2):156-159.

- Robertson JJ, Long B, Koyfman A. Myths in the evaluation and management of ovarian torsion. J Emerg Med. 2016;52(4):449-456.

- White M, Stella J. Ovarian torsion: a 10-year perspective. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17(3):231-237.

- Huchon C, Panel P, Kayem G, et al. Does this woman have adnexal torsion? Hum Reprod. 2012;27(8):2359-2364.

- Varras M, Tsikini A, Polyzos D, et al. Uterine adnexal torsion: Pathologic and gray-scale ultrasonographic findings. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2004;31(1):34-38.

- Bouguizane S, Bibi H, Farhat Y, et al. Adnexal torsion: a report of 135 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2003;32(6):535-540.

- Tsafrir Z, Hasson J, Levin I, et al. Adnexal torsion: cystectomy and ovarian fixation are equally important in preventing recurrence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;162(2):203-205.

- Anders JF, Powell EC. Urgency of evaluation and outcome of acute ovarian torsion in pediatric patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005; 159(6):532-535.

- Tsafrir Z, Azem F, Hasson J, et al. Risk factors, symptoms, and treatment of ovarian torsion in children: the twelve-year experience of one center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(1):29-33.

- Worthington-Kirsch RL, Raptopoulos V, Cohen IT. Sequential bilateral torsion of normal ovaries in a child. J Ultrasound Med. 1986;5(11):663-664.

- Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, et al. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):1098-1103.

- Gorkemli H, Camus, M, Clasen K. Adnexal Torsion after gonadotropin ovulation induction for IVF or ICSI and its conservative treatment. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002;267(1):4-6.

- Chiou SY, Lev-Toaff AS, Masuda E, et al. Adnexal torsion: new clinical and imaging observations by sonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(10):1289-1301.

- Albayram F, Hamper UM. Ovarian and adnexal torsion: spectrum of sonographic findings with pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20(10):1083-1089.

- Hasson J, Tsafrir Z, Azem F, et al. Comparison of adnexal torsion between pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):536.e1-6.

- Johnson TR Jr, Woodruff JD. Surgical emergencies of the uterine adnexae during pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1986;24(5):331-335.

- Yen CF, Lin SL, Murk W, et al. Risk analysis of torsion and malignancy for adnexal masses during pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(5):1895-1902.

- Karaman E, Beger B, Çetin O, et al. Ovarian torsion in the normal ovary: a diagnostic challenge in postmenarchal adolescent girls in the emergency department. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:1312-1316.

- Rey-Bellet Gasser C, Gehri M, Joseph JM, et al. Is it ovarian torsion? A systematic literature review and evaluation of prediction signs. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(4):256-261.

- Ashwal E, Hiersch L, Krissi H, et al. Characteristics and management of ovarian torsion in premenarchal compared with postmenarchal patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):514-520.

- Ashwal E, Krissi H, Hiersch L, et al. Presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of ovarian torsion in premenarchal girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(6):526-529.

- Schmitt ER, Ngai SS, Gausche-Hill M, et al. Twist and shout! Pediatric ovarian torsion clinical update and case discussion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(4):518-523; quiz 524-526.

- Poonai N, Poonai C, Lim R, et al. Pediatric ovarian torsion: case series and review of the literature. Can J Surg. 2013;56(2):103-108.

- Cicchiello LA, Hamper UM, Scoutt LM. Ultrasound evaluation of gynecologic causes of pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;38(1):85-114.

- Taskin O, Birincioglu M, Aydin A, et al. The effects of twisted ischaemic adnexa managed by detorsion on ovarian viability and histology: an ischaemia-reperfusion rodent model. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(10):2823-2827.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, et al. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2599-2602.

- Close RJH, Sachs CJ, Dyne PL. Reliability of bimanual pelvic examinations performed in emergency departments. West J Med. 2001;175(4):240-244.

- Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Accuracy of the pelvic examination in detecting adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(4):593-598.

- Ueland FR, Depriest PD, Desimone CP, et al. The accuracy of examination under anesthesia and transvaginal sonography in evaluating ovarian size. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99(2):400-403.

- Swenson DW, Lourenco AP, Beaudoin FL, et al. Ovarian torsion: case-control study comparing the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography and computed tomography for diagnosis in the emergency department. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(4):733-738.

- Wilkinson C, Sanderson A. Adnexal torsion—a multimodality imaging review. Clin Radiol. 2012;67(5):476-483.

- Ben-Ami M, Perlitz Y, Haddad S. The effectiveness of spectral and color Doppler in predicting ovarian torsion. A prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;104(1):64-66.

- Nizar K, Deutsch M, Filmer S, et al. Doppler studies of the ovarian venous blood flow in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009;37(8):436-439.

- Valsky DV, Esh-Broder E, Cohen SM, et al. Added value of the gray-scale whirlpool sign in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(5):630-634.

- Vijayaraghavan SB, Senthil S. Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube: the sonographic whirlpool sign. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28(5):657-662.

- Hiller N, Appelbaum L, Simanovsky N, et al. CT features of adnexal torsion. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(1):124-129.

- Dhanda S, Quek ST, Ting MY, et al. CT features in surgically proven cases of ovarian torsion—a pictorial review. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1078):20170052.

- Duigenan S, Oliva E, Lee SI. Ovarian torsion: diagnostic features on CT and MRI with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(2):W122-131.

- Moore C, Meyers AB, Capotasto J, et al. Prevalence of abnormal CT findings in patients with proven ovarian torsion and a proposed triage schema. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16(2):115-220.

One Response to “Dispelling 5 Ovarian Torsion Myths”

July 5, 2020

Jerry W. Jones, MD FACEP FAAEMExcellent article. Very concise and right to the point.