Explore This Issue

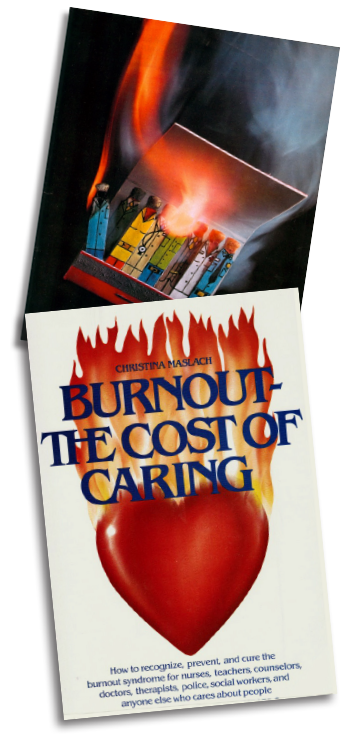

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 09 – September 2018TOP: Image from the cover of the issue of Human Behavior magazine where Dr. Maslach published her first article in 1976.

BOTTOM: Cover of Burnout: The Cost of Caring, published in 1982.

PHOTOS: Christina Maslach

When Christina Maslach, PhD, started her psychology research career in the early 1970s, she didn’t know that her work would lead to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a measure for professional burnout that’s still being used today. She first published the inventory with coauthor Susan E. Jackson in 1981. Dr. Maslach, who is professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, has researched and published extensively about burnout throughout her career, and has helped to define the way we discuss and understand the combination of stress, exhaustion, and powerlessness that endangers the careers—and lives—of many emergency physicians.

ACEP Now Medical Editor-in-Chief Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, recently sat down with Dr. Maslach to discuss the early research that led to her developing the Maslach Burnout Inventory and what she’s learned from decades of talking to people about burnout. Here is Part 1 of their conversation. Part 2 will appear in the October issue.

KK: Tell us how your background led you to work on this particularly important topic.

CM: I received a PhD in social psychology from Stanford University, and then I took a job at the University of California at Berkeley, where I’ve been for the rest of my career. I had done research on emotion while I was in the doctoral program, particularly focusing on how people dealt with some of the emotional challenges or crises they might experience.

At Berkeley, I wasn’t able to start doing my research because they hadn’t yet provided me with a research facility. So, I thought I’d go and interview some people who might give me some insight into their experience. From that, I would develop some hypotheses and research and so forth. I started interviewing some people who I thought might face these kinds of emotional challenges. I was talking with, in terms of health care, for example, physicians who were working in emergency departments, with oncology wards, and nurses—and people would keep referring me to somebody else—just talking to psychiatric nurses, police officers, ministers, and different people who sometimes had some very difficult situations.

What I found in the interviews was very serendipitous. I had never heard about burnout. I wasn’t talking about burnout, but what was happening in the interviews is that people would say, “Here’s what’s happening. I know this is confidential, so I’ve never really said much about it to anybody, but …” Then they would be describing their particular story, and what I found was there was a kind of a rhythm to the story; there were some fairly common themes.

One day, I was talking with someone who had been working in poverty law, and she said, “That sounds familiar. I don’t know what they call it elsewhere, but we call it burnout.” I would ask people at the end of the interview if they ever describe this to other people, and if so, how did they talk about. I never got much of an answer.

I described some concepts that appear in sociology, psychology, health literature, and they’d say, “No, no, no.” Then I added, “So, what about burnout?” “Yeah, that’s it, oh my gosh.” What I was finding was it was really not a psychological concept, but it was something that was really a grassroots sort of thing. The people themselves said this term captured what they were feeling. After that I would use “burnout” at the end of the interview to talk with them about it.

KK: What time frame was this?

CM: This was in the early to mid ‘70s.

KK: Did this prompt you to then do the survey?

Dr. Christina Maslach

CM: Yes. All of that work came out of this original experience. I was doing interviews with different people, and then when possible, I would observe them at work to see what their work day was like. I talked to their colleagues, or we talked to spouses of these people. We were trying to get a sense from people who knew this person, worked with them, and maybe shared the same kind of experiences. Although it wasn’t something that I had intended to do, or that I set out with a mission to define burnout, but once I stumbled over it, it was clear that there was something really important about this.

I had a hard time getting published at first. It wasn’t laboratory research like I had been trained to do. My first article about this was written for a popular magazine called Human Behavior. They published it in 1976, and in an interesting way, that was maybe a better spot for all of the things I did on burnout because that generated tons of feedback. These were snail mail days. Tons of letters and phone calls. People would say, “Oh my gosh. I thought I was the only one. Let me tell you my story.” I just felt I had stumbled upon something that was not well-known, not well-recognized. I was told it was pop psychology. People’s experiences inspired me to continue this work, not to abandon other research I was doing, but to add this focus. After a while, it became more and more the main work that I was doing.

KK: Can you describe how hard it was and what the process was for you to develop the survey or the burnout inventory?

CM: The problem is that you have to develop a measurement that has evidence proving it is clearly measuring what it is that you say it’s measuring.

It looks straightforward. People say, “Oh, it’s easy. I’ll just write a few questions of my own.” Well, you have no idea if those questions are working correctly or not. There’s something called face validity, which makes it sound right, but you need to gather other data to really test out which items, questions that you’re using, and formats are really working well to measure what you say is being measured. Psychometric research took years and years of work by me, Susan Jackson, other students, and other colleagues because we had to gather data on so many people in so many different ways to be able to triangulate on, proving that this was the thing that people were talking about [burnout].

I was fortunate because the professor in psychology who was one of the leading people in assessing psychological constructs was a member of my department, Harrison Golf. He really became my mentor, and made clear to me what it was that I had to do. It was really on-the-job training to do this. It took a long time, but it turned out well, in the sense of meeting all the criteria that you need for such a measure. Even though that was more than 40 years ago, it’s still stood the test of time, and other measures that get developed are always comparing themselves to this standard. It surprises me a bit because I would have thought that people would have updated things or maybe come up with better options or done other sorts of things. I think all the work that we put in at that time has contributed to that.

KK: Did you have any idea that what you were developing would have the impact that it has today?

CM: No, not at all. I have to say, way back then, it wasn’t only the editors of journals who would turn my articles away and not even read them because they said, “We don’t publish pop psychology.” It took a long time to get people to believe there was something there.

KK: Did you ever get discouraged?

CM: My interest in the topic really was stoked by the experiences of the people that I kept talking to over time, and that’s true even now. I’d be interviewing people, and they were getting angry and upset, and they’re crying. This was not something trivial. This really matters. People tell me stories about how this has affected their family and how they’ve made decisions they now wish they hadn’t. It was something that fascinated me.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Dr. Christina Maslach Discusses the Roots of Burnout”