In 2001, when we had agitated patients in the emergency department, we’d give them intramuscular droperidol and everything would be fantastic. It also worked well for nausea and vomiting, and was a useful adjunct for headache treatment.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 09 – September 2019But then because of concerns related to prolongation of the QT interval on ECG, the threat of torsades de pointes, and persistent shortages of the drug, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a widely criticized warning that recommended a screening ECG prior to dosing, telemetry for two to three hours following administration, and a contraindication for patients with a long QTc (with a cutoff at >440 ms for males, >450 ms for females).1 In short order, droperidol disappeared from hospitals in the United States, the United Kingdom, and many other places, despite the fact that other medications like haloperidol had the same theoretical risks and remained widely available. But now, injectable droperidol is back, courtesy of manufacturer American Regent. Much of the body of knowledge regarding the clinical use of droperidol has eroded over time, so here’s what you need to know:

Dosing and Benefits

First, droperidol at the 5–10 mg doses (intravenous [IV] or intramuscular [IM]) used for sedation and control of agitation is safe. Onset of action can be expected within 5–10 minutes IM, and a bit faster IV, though studies suggest full effects may not be apparent for up to 20–30 minutes, at which time redosing can be considered. IM haloperidol, on the other hand, works far more slowly than droperidol, often taking 20–30 minutes for onset. In fact, the main advantage of droperidol for agitated patients is precisely in those without IV access. IV haloperidol works fine for psychosis. But without an IV line in place, the delayed onset with IM haloperidol is not workable in the emergency department setting, which is why it is so often mixed with benzodiazepines (“5 and 2” just flies off the tongue; more on that later).

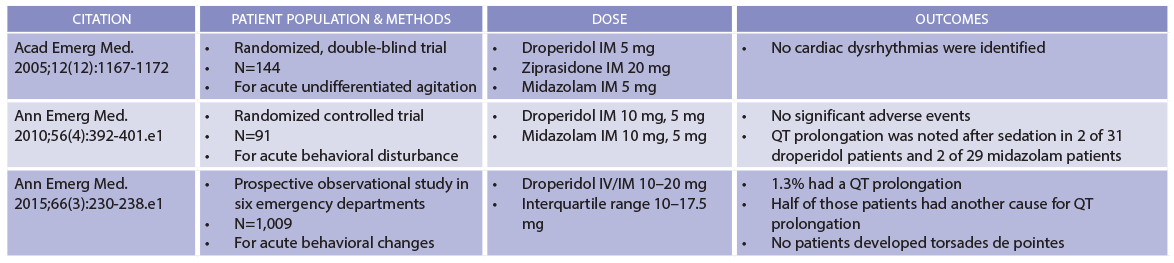

The FDA warning, which it bears noting has not been revised, uses 2.5 mg as its threshold for concern. But there is no good evidence to support this approach. True, some people who received droperidol have developed torsades but only after receiving absolutely gargantuan doses, totaling more than 300 mg. Droperidol’s cardiovascular safety is supported by a series of studies that found none of the more than 1,200 agitated patients who received the drug developed torsades (see Table 1).2-4 Some patients did exhibit prolongation of the QT interval, but a substantial proportion of patients had additional reasons for prolonged repolarization. Although these data were collected in emergency departments, studies in prehospital and anesthesia settings have added heft to the finding that sedating doses of droperidol cause neither clinically significant QT prolongation nor torsades. In short, droperidol is safe.

(click for larger image) Table 1: Droperidol Safety Data

Compiled by Brigham and Women’s Hospital Drug Safety Committee.

Second, droperidol is a smarter choice for sedation than lorazepam. Clinical trials have demonstrated that agitated patients need additional doses of lorazepam five times more frequently than those receiving droperidol.5 In other words, while a patient may need only a single 5 mg dose of droperidol, a comparable patient may need 2 mg lorazepam—again and again and again and again. The issue here is one of pharmacodynamics. Physicians often recognize that lorazepam has a relatively short plasma half-life, but control of agitation is a pharmacodynamic effect. Lorazepam has slower central nervous system (CNS) penetrance, so sedation is delayed. Because achieving sedation takes longer, clinicians often give additional doses of lorazepam before the previous dose has fully taken effect. The serial administration of lorazepam is a real problem. Sedation following parenteral lorazepam typically lasts six to eight hours, but sedation following repeat dosing can persist even longer, sometimes up to 24 hours.

Droperidol avoids the oversedation commonly seen in lorazepam (and other benzodiazepine) therapy. Droperidol, with its brisk CNS penetrance, sedates faster, so clinicians can “tune” the degree of behavioral control to a particular clinical scenario, eliminating frequently incorrect stacked dosing of benzodiazepines. This alone may help avoid an unnecessary hospitalization of a patient who—after receiving multiple doses of lorazepam—“just won’t wake up.” Using droperidol instead has the potential to decrease lengths of stay for intoxicated patients who have temporarily become a belligerent threat to themselves and others in the emergency department.

Third, droperidol is a better choice for controlling agitation than haloperidol, which became the mainstay choice over the last 20 years during which droperidol was largely unavailable here. While haloperidol is a superb antipsychotic, it is a lousy sedative. That’s why a sedative (such as lorazepam) is often needed for behavioral control—we’ve known since at least the 1980s that haloperidol alone simply doesn’t cut it—thus the “5 and 2” strategy that has become the reflexive approach for controlling the agitated ED patient. Single drug therapy is often safer than polypharmacy, an aphorism supported by studies pitting droperidol versus haloperidol plus lorazepam. Lorazepam tends to oversedate patients, often for long periods of time. For those of us old enough to be familiar with droperidol’s wondrous ability to rapidly control agitation without snockering the patient for hours, we remember that its use translated into simpler dispositions; formerly agitated drunks essentially “went down” but could be easily awakened and discharged by shift’s end.

Finally—and this is important for emergency physicians—there is no need for an ECG prior to droperidol administration at common ED doses. Continuous cardiovascular monitoring to detect torsades is not mandated and usually unnecessary. This is based upon the knowledge that any observed QT prolongation following droperidol administration is both uncommon and, even if present, almost always clinically insignificant. Interestingly, data from some studies seem to suggest that lorazepam is actually more likely to be associated with QT prolongation, although the mechanism for this is not clear and it certainly did not lead to cardiac dysrhythmias.3

Conclusion

Overall, droperidol sedates faster and more cleanly than haloperidol or lorazepam, either alone or in combination. Data support not obtaining screening ECGs and continuous cardiovascular monitoring is not required. Droperidol was, in years past, the first-line therapy for sedation; the time has come for it to return to that status.

Dr. Boyer is director of research and academic development at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and associate professor of emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Perkins J, Ho JD, Vilke GM, et al. American Academy of Emergency Medicine position statement: safety of droperidol use in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(1):91-97.

- Martel M, Sterzinger A, Miner J, et al. Management of acute undifferentiated agitation in the emergency department: a randomized double-blind trial of droperidol, ziprasidone, and midazolam. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(12):1167-1172.

- Isbister GK, Calver LA, Page CB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intramuscular droperidol versus midazolam for violence and acute behavioral disturbance: the DORM study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(4):392-401.e1.

- Calver L, Page CB, Downes MA, et al. The safety and effectiveness of droperidol for sedation of acute behavioral disturbance in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(3):230-238.e1.

- Richards JR, Derlet RW, Duncan DR. Chemical restraint for the agitated patient in the emergency department: lorazepam versus droperidol. J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):567-573.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

3 Responses to “Droperidol Is Back (and Here’s What You Need to Know)”

October 19, 2019

Marguerite WrightExcellent article. It would be interesting to follow the use of this drug as it becomes more widely used in the acute clinical setting.

November 21, 2019

Marc Hoffman,MDDr. Boyer,

We are currently trying to get droperidol back on formulary at Mercy Hospital in Portland, for use in the ED. At Brigham, it seems you are not checking the QTc, am I correct? Is there a subset of patients you check the QTc on once they are more sedate?

December 28, 2019

M Bruce Parker MD FACEPI have presented this [& other] articles

to the EDs where I work, to no avail.

Will we wait another 17 years for a new generation of managers to not remember thinking inside this box? When there is no money to be made, progress is slow.