I have good friends in Liberia. I know the culture, the politics, and the medical system there. Once the news broke in March 2014 that the Ebola virus disease (EVD) epidemic was spreading into Liberia, I knew I had to do something to help. Due to some prior health issues, I couldn’t automatically assume that the best way I could help was to provide on-scene acute medical care.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 02 – February 2015In 2004, I developed an autoimmune neurological disease and subsequently also developed some significant issues with my eyesight. I stepped down as emergency department medical director, and I’ve made some lifestyle adjustments since then. Despite improvements in my condition, it was an unknown variable whether the intense heat inside the isolation suits and the limited visibility through the goggles or face masks would limit my effectiveness. The last thing I wanted was to become a liability to a medical system that was already in crisis.

To better understand what my options might be, I aggressively started researching the Ebola virus. I also began to study exactly how the epidemic was unfolding. Within weeks, it became clear to me that the overall relief effort was beginning to experience some serious logistical problems. My friends and I decided to see what we could do to help.

Focus on Transportation

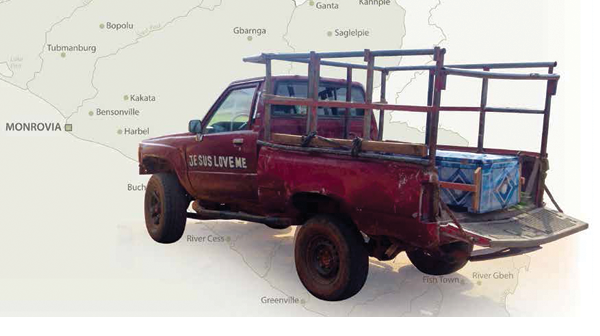

Like any large humanitarian operation, the problems were legion, but the most salient logistical problems from my perspective were all in the area of transportation. The international community was starting to address the lack of personal protective equipment and medical personnel, but no one seemed to be noticing that there weren’t enough reliable and task-specific vehicles available in the country to transport these resources to where they needed to go. There wasn’t an emergency medical services (EMS) system, and the few ambulances available were either privately owned or in disrepair.

How were people sick with Ebola supposed to get to the new Ebola treatment units (ETUs)? People had to walk, be carried, ride a bicycle or motorbike, or travel in a private vehicle (usually a Toyota Corolla–sized taxi). People sick with Ebola or those transporting their deceased relatives had to pay to travel in these private taxis, and sometimes, to defray the costs, they did so with other passengers aboard. In fact, in December 2014 a taxi driver was arrested for transporting the corpse of someone who had died of EVD.

It was a very eclectic group of donors that rallied around the cause: humanitarians, a Christian ministry, several Muslim Lebanese businessmen, a US pharmacist, a CEO of an international medical corporation, a US/Liberian forestry and mining company, a physician, a physician assistant, and 20 dedicated Liberians all played a part in making things happen.

Early in the epidemic, there weren’t enough hearses or trucks to collect the bodies in the streets or to form the county burial teams that are now in place. Contact tracers and Ebola awareness teams didn’t have the transportation needed to visit the communities they were being assigned to reach. To make matters worse, Liberia was entering its rainy season, and for the next five months, the jungle roads were about to become very difficult to navigate even using all-wheel drive a rut).

My friends quickly formed a 501(c)(3) charity, and between our group and another, we collected about $150,000 worth of resources. It was a very eclectic group of donors that rallied around the cause: humanitarians, a Christian ministry, several Muslim Lebanese businessmen, a US pharmacist, a CEO of an international medical corporation, a US/Liberian forestry and mining company, a physician, a physician assistant, and 20 dedicated Liberians all played a part in making things happen. The one common denominator we all shared was the determination to make a difference.

Above: Dr. Bollard standing beside Ebola prevention supplies in Monrovia.

Right: The road conditions as we traveled to deliver supplies to rural villages were very bad, as shown by this commercial truck stuck in a rut in River Gee County, Liberia.

Inset: The Renault delivery truck stuck in the mud in River Gee County, Liberia.

Putting Plans Into Action

Our original intention was to use that money to acquire and refurbish as many old ambulances as we could and to ship them to Liberia as quickly as possible. Within a month, that plan had to change because several countries had recognized Liberia’s transportation problems and started shipping them a large number of service vehicles. We shifted our primary focus from acquiring ambulances to transporting supplies to communities that would be very difficult for the mainline relief organizations to reach.

Our first ambulance shipped to the Liberia Medical & Dental Council (LMDC) in Monrovia. The LMDC thought of a novel way to use it to bring hope and education to communities within the country’s capital city. Its current plan is to use the ambulance to transport Ebola survivors (with lights flashing and sirens blaring) directly from the ETUs they are leaving back to their home communities (see Figure 4). We hope that the presence of this impressive rig and the celebration and education that will accompany its arrival in various Liberian communities will advance the relief effort.

The remaining funds were used to purchase and deliver food and sanitation supplies and to bring Ebola awareness campaigns to multiple rural communities we knew probably wouldn’t have been reached until after the rainy season. We hired drivers and all-wheel drive Renault vehicles from a mining company and transported bed linens, rice, buckets with faucets for hand washing, bleach, alcohol, powdered soap, pharmaceuticals, oral rehydration solutions, and personal protective equipment to approximately 25 communities and medical clinics. It took days to reach some of these villages, and they knew what an effort it was for us to make such a trip during the rainy season. They were grateful for the supplies and were eager to learn how to protect themselves during the EVD epidemic.

The ambulance for the Liberia Medical & Dental Council before it was shipped from Pennsylvania to Liberia.

In closing, I’d like to thank my colleagues in ACEP for all the wisdom and professional encouragement given to me during the planning stages of this adventure. The responses to the queries I posted on the EMS, Disaster, International, and Tactical Medicine mailing lists were invaluable. Emergency physicians, as a group, are the most multitalented individuals I’ve ever worked with. When they volunteer to work during a disaster or a humanitarian crisis, they bring with them not only their medical skills but frequently many other gifts as well. Utilizing those additional talents can sometimes be critical to the overall success of the relief effort.

Whenever possible, a physician volunteer should be vetted and only work in these situations under the aegis of an established relief organization. There are occasions, however, when an individual or a small group of individuals with the proper background, resources, and action plan can achieve operational objectives that the larger relief organizations just can’t. First, do no harm!

Dr. Bollard is a former ED director and co-founder of the ACEP Tactical Emergency Medicine Section. He currently works as an operational medicine consultant for various EMS, fire, and law enforcement agencies across the country. He resides in Bozeman, Montana.

Dr. Bollard is a former ED director and co-founder of the ACEP Tactical Emergency Medicine Section. He currently works as an operational medicine consultant for various EMS, fire, and law enforcement agencies across the country. He resides in Bozeman, Montana.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Ebola Relief Efforts in Liberia Aided by Emergency Medicine Support, Donations”