Finally, a repeat ultrasound of the abdomen can be performed to see if there is progression of real time intra-abdominal bleeding. Conversely, a positive eFAST in a hemodynamically stable patient (e.g., small pneumothorax or trace hemoperitoneum) should be clearly communicated to the trauma team, but should likely not delay advanced imaging with CT.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 09 – September 2022

FIGURE 2: Monitors are placed at the head of the trauma bay so that all members of the trauma team are able to view the ultrasound images during

an eFAST examination. (Click to enlarge)

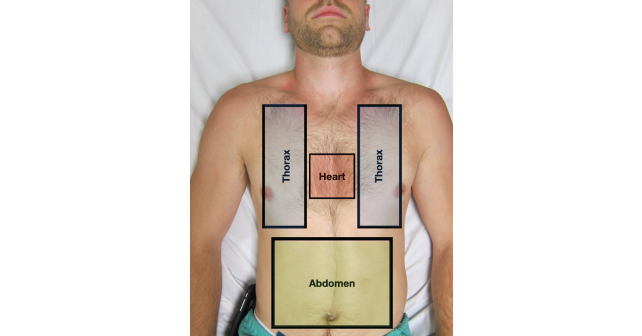

At Highland Hospital, we have implemented a simple technological solution that allows for bidirectional and objective communication. Monitors that wirelessly mirror POCUS images from an eFAST examination were secured on the wall above the head of the bed allowing the entire trauma team to easily view real-time images. Data (either positive or negative findings) are verbally communicated to the trauma team in our “three box” format as images are projected for the trauma leader to view. This allows the trauma sonographer to replay images and discuss findings with trauma leaders to ensure that decisions are made in a clear and consensual manner (See Figure 2—https://www.aliem.com/idea-series-big-screen-ultrasound-resuscitation-bays/).

3. Negative eFAST in the Setting of a Hypotensive Trauma Patient

After a negative eFAST exam in a persistently or newly hypotensive trauma patient, other significant pathologies must be considered. We employ a simple algorithm to help remind our sonographers during this uncommon, yet cognitively challenging scenario. First, consider an unstable pelvic fracture leading to a large retroperitoneal injury. The eFAST is insensitive for free fluid in the retroperitoneum including the pelvis, therefore empiric pelvic binder placement can reduce further suspected hemorrhage.12 Second, repeat the eFAST examination to evaluate for interval changes such as increased intraperitoneal free fluid or an enlarging pneumothorax/hemothorax. A repeat FAST exam has been shown to significantly increase the sensitivity for free fluid in blunt trauma.13 Third, we recommend a more detailed echocardiographic examination including evaluation for valvular injury, underlying poor cardiac function, secondary signs of aortic dissection (e.g., trace pericardial effusion, large left ventricular outflow tract, or aortic insufficiency), or other cardiac obstructive causes (e.g., right heart strain concerning for pulmonary embolism, regional wall motion abnormalities suggestive of ST elevation myocardial infarction) which may have been the initial insult leading to the traumatic injury (e.g., STEMI resulting in MVC).14 Finally, consideration of neurogenic shock and other causes of traumatic hypovolemia that may not be apparent on eFAST (e.g., retroperitoneum, thigh, or external blood loss on scene) should always be occurring in parallel. Remember, a bidirectional and open conversation with your trauma colleagues will allow for the best care for your critically ill trauma patient.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 | Single Page

No Responses to “eFAST 2.0: Refining an Integral Trauma Exam”