The initial proposal by Rozycki et al., in 1993 on the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) exam was a novel and systematic approach for the utilization of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) during the initial trauma survey.4 Although ultrasound was first described in the 1970s, this algorithm provided the framework for an integral component of our current trauma evaluation, largely replacing the need for diagnostic peritoneal lavage for the diagnosis of intraperitoneal hemorrhage.1–3 It was not until 2004 that Kirkpatrick et al., published in the Journal of Trauma the protocol of the extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (eFAST) exam incorporating the thorax in addition to the heart and abdomen assessment.4

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 09 – September 2022Emergency physicians have been champions for implementing and teaching this invaluable tool into the culture of trauma care, altering the clinical care pathway for numerous critically ill trauma patients. After our nearly two decades of experience performing and interpreting the eFAST exam at a Level I trauma center, we believe that this durable bedside examination can benefit from a further nuanced conceptualization and approach.

Incorporating the eFAST Exam

Compared to when POCUS was first implemented for the assessment of trauma, computed tomography (CT) scanners have become faster (and more accurate), resuscitation theory has advanced, and the literature’s approach to traumatic injuries has changed.5,6 In response to these changes, emergency physicians must determine the optimal ways of incorporating the eFAST exam. The goal of the eFAST examination for emergency physicians is not to replace CT imaging, but to complement modern trauma care in an evidence-based and practical manner.

Although emergency physicians have successfully incorporated the eFAST examination into the evaluation of patients with both blunt and penetrating trauma, we feel that the following recommendations can further enhance bedside decision making during your next critically-ill trauma resuscitation.

1. The “Three Box Concept”

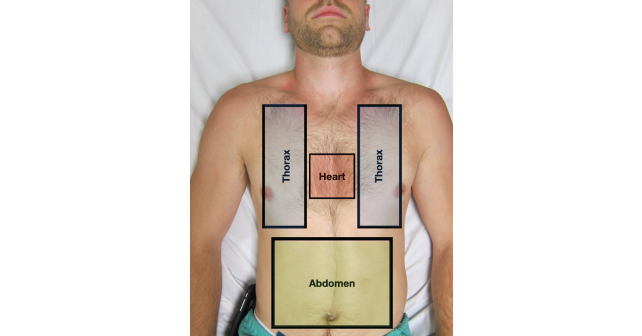

FIGURE 1: A representation of the “three box concept” indicating the locations that need to be interrogated during an eFAST examination. (Click to enlarge)

When evaluating the acutely injured trauma patient, emergency physicians should be aware of the “three box concept” (See Figure 1). The thorax, heart, and abdomen comprise the three “boxes” that should be sonographically interrogated in order to determine whether an emergent intervention is warranted in the trauma bay, further imaging should be pursued, or the patient needs to proceed directly to the operating room (OR). In our experience, the order in which these “boxes’’ are evaluated as part of the eFAST should be based on the mechanism of injury as well as the patient’s clinical status. For example, patients with penetrating injuries to the chest should be initially evaluated for the presence or absence of pericardial effusion, pneumothorax, and hemothorax. A massive hemothorax/pneumothorax or a hemopericardium that is causing hemodynamic compromise may force the emergency physician to perform stabilization measures at the bedside (e.g., tube thoracostomy, pericardiocentesis, ED thoracotomy) without further imaging, or prompt the trauma surgeon to take the patient directly to the OR. If sonographic evaluation of these two boxes fails to reveal emergent pathology, evaluate the abdomen for the presence or absence of free fluid. Presence of hemoperitoneum in a hemodynamically unstable trauma patient classically leads to a direct need for operative intervention.

Alternatively, in the blunt trauma patient with hemodynamic compromise, the thorax and abdomen should be the first two boxes evaluated by eFAST. This approach can clarify the need for early tube thoracostomy in the setting of massive hemothorax/pneumothorax or help guide the trauma team to pursue operative stabilization if massive hemoperitoneum is noted. In contrast, significant hemopericardium following blunt trauma is an uncommon and often non-survivable event, and thus the pericardium should be scanned after the other two boxes are rapidly and thoroughly evaluated.7

The eFAST exam is highly specific for free fluid in the abdomen and highly sensitive for pneumothorax, hemothorax, and pericardial effusion.8–10 Therefore, most emergency physicians utilize the eFAST in unstable patients to decide whether or not the patient needs rapid operative stabilization or can undergo further CT imaging.

2. Goal-Directed Communication

The eFAST examination findings must be properly communicated when working alongside your trauma colleagues. There should be bidirectional communication with the trauma team leader to facilitate appropriate and timely intervention while always taking into account the patient’s clinical status. The eFAST is not a binary test—the interpretations are nuanced and the assessment of the “three boxes” should be interpreted in real time. Communication to the trauma team should be in a granular or detailed manner so that these results can properly be incorporated into the care of the patient.

When communicating these results to the trauma team, it is critical to interpret both positive and negative eFAST exams in the context of the patient’s clinical status. For example, in the patient with a blunt abdominal injury and a trace amount of free fluid in Morrison’s pouch, this source of bleeding is unlikely the cause of significant hypotension as the hemorrhagic volume needs to be much greater than the minimum 150 to 200mL required to be visualized on an eFAST.8 This is in contrast to advanced trauma life support (ATLS) hemorrhagic shock classifications where blood pressure would not typically lower until class III shock (1500–2000mL of blood loss).11 While this should be reported as a “positive” abdominal component of the eFAST examination for documentation purposes, it is imperative to communicate to the trauma team leader that this degree of free fluid in the abdomen does not clinically correlate with the patient’s hemodynamic instability. Alternative or concurrent injuries in the other two boxes (e.g., thorax or heart) or the possibility of an unstable pelvis/retroperitoneal injury or long bone injury and/or neurogenic shock should also be considered.

Finally, a repeat ultrasound of the abdomen can be performed to see if there is progression of real time intra-abdominal bleeding. Conversely, a positive eFAST in a hemodynamically stable patient (e.g., small pneumothorax or trace hemoperitoneum) should be clearly communicated to the trauma team, but should likely not delay advanced imaging with CT.

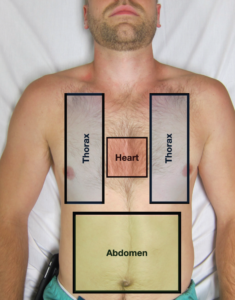

FIGURE 2: Monitors are placed at the head of the trauma bay so that all members of the trauma team are able to view the ultrasound images during

an eFAST examination. (Click to enlarge)

At Highland Hospital, we have implemented a simple technological solution that allows for bidirectional and objective communication. Monitors that wirelessly mirror POCUS images from an eFAST examination were secured on the wall above the head of the bed allowing the entire trauma team to easily view real-time images. Data (either positive or negative findings) are verbally communicated to the trauma team in our “three box” format as images are projected for the trauma leader to view. This allows the trauma sonographer to replay images and discuss findings with trauma leaders to ensure that decisions are made in a clear and consensual manner (See Figure 2—https://www.aliem.com/idea-series-big-screen-ultrasound-resuscitation-bays/).

3. Negative eFAST in the Setting of a Hypotensive Trauma Patient

After a negative eFAST exam in a persistently or newly hypotensive trauma patient, other significant pathologies must be considered. We employ a simple algorithm to help remind our sonographers during this uncommon, yet cognitively challenging scenario. First, consider an unstable pelvic fracture leading to a large retroperitoneal injury. The eFAST is insensitive for free fluid in the retroperitoneum including the pelvis, therefore empiric pelvic binder placement can reduce further suspected hemorrhage.12 Second, repeat the eFAST examination to evaluate for interval changes such as increased intraperitoneal free fluid or an enlarging pneumothorax/hemothorax. A repeat FAST exam has been shown to significantly increase the sensitivity for free fluid in blunt trauma.13 Third, we recommend a more detailed echocardiographic examination including evaluation for valvular injury, underlying poor cardiac function, secondary signs of aortic dissection (e.g., trace pericardial effusion, large left ventricular outflow tract, or aortic insufficiency), or other cardiac obstructive causes (e.g., right heart strain concerning for pulmonary embolism, regional wall motion abnormalities suggestive of ST elevation myocardial infarction) which may have been the initial insult leading to the traumatic injury (e.g., STEMI resulting in MVC).14 Finally, consideration of neurogenic shock and other causes of traumatic hypovolemia that may not be apparent on eFAST (e.g., retroperitoneum, thigh, or external blood loss on scene) should always be occurring in parallel. Remember, a bidirectional and open conversation with your trauma colleagues will allow for the best care for your critically ill trauma patient.

Summary

The eFAST examination has become a cornerstone of the evaluation of the critically ill trauma patient. The clinical context of the injury and hemodynamic status must be incorporated into the order and interpretation of the exam components. Utilize the “three box” concept as a framework and modify the order of the eFAST components depending on the mechanism of trauma and the patient’s clinical status. Proper and granular communication of ultrasound findings should be relayed to your trauma colleagues and interpreted in the hemodynamic clinical context of the patient. Finally, when faced with the newly or persistently hypotensive patient after an initially negative eFAST exam, a structured algorithm should be employed to reduce cognitive load in an often stressful situation. Our simple additions to the eFAST examination in no way replace the amazing work done by numerous physicians who have brought this life-saving tool into trauma care, but rather a minor refinement to an integral exam in modern trauma resuscitation.

Dr. Leu is an ultrasound fellow at Highland Hospital.

Dr. Mantuani is the ultrasound fellowship director at Highland Hospital.

Dr. Sobrero is an ultrasound fellow at Highland Hospital.

Dr. Nagdev is director of emergency ultrasound at Highland Hospital.

References

- Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Jaffin JH, et al. Prospective evaluation of surgeons’ use of ultrasound in the evaluation of trauma patients. J Trauma. 1993;34(4):516–527.

- Kristensen JK, Buemann B, Kühl E. Ultrasonic scanning in the diagnosis of splenic haematomas. Acta Chir Scand. 1971;137(7):653–657.

- Montoya J, Stawicki SP, Evans DC, et al. From FAST to E-FAST: an overview of the evolution of ultrasoundbased traumatic injury assessment. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016;42(2):119–126.

- Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Laupland KB, et al. Hand-held thoracic sonography for detecting post-traumatic pneumothoraces: the Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (EFAST). J Trauma. 2004;57(2):288–295.

- Galvagno SM Jr, Nahmias JT, Young DA. Advanced trauma life support update 2019: management and applications for adults and special populations. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019;37(1):13–32.

- Gondek S, Schroeder ME, Sarani B. Assessment and resuscitation in trauma management. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97(5):985–998.

- Press GM, Miller S. Utility of the cardiac component of FAST in blunt trauma. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):9–16.

- Bloom BA, Gibbons RC. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma. [Updated 2022 May 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

- Wilkerson RG, Stone MB. Sensitivity of bedside ultrasound and supine anteroposterior chest radiographs for the identification of pneumothorax after blunt trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(1):11–17.

- Mandavia DP, Hoffner RJ, Mahaney K, et al. Bedside echocardiography by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(4):377–382.

- American College of Surgeons Trauma Committee. Advanced trauma life support for doctors. 8th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

- Friese RS, Malekzadeh S, Shafi S, et al. Abdominal ultrasound is an unreliable modality for the detection of hemoperitoneum in patients with pelvic fracture. J Trauma. 2007;63(1):97–102.

- Blackbourne LH, Soffer D, McKenney M, et al. Secondary ultrasound examination increases the sensitivity of the FAST exam in blunt trauma. J Trauma. 2004;57(5):934–938.

- Thomas B, Durant E, Barbant S, et al. Repeat point-of-care echocardiographic evaluation of traumatic cardiac arrest: a new paradigm for the emergency physician. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2017;1(3):194–196.

No Responses to “eFAST 2.0: Refining an Integral Trauma Exam”