Explore This Issue

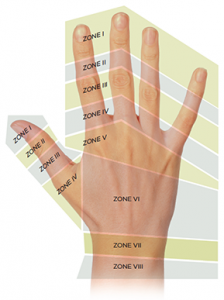

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 12 – December 2015Figure 1. Extensor injury zones.3

Image Credit: ILLUSTRATION/PAUL JUESTRICH; PHOTOs shutterstock.com

The hand is an intricate structure that provides us with the dexterity needed for our everyday lives. Unfortunately, we see many patients in the emergency department who take this functionality for granted until they lose all or part of it. The attention spent on flexor tendon injuries is pervasive throughout the literature, whereas the more common extensor tendon injuries have not garnered as much attention.1 As emergency physicians, we have the opportunity to decrease the amount of impairment that patients sustain from these extensor tendon injuries by providing them with the appropriate treatment that they deserve.

Diagnosing an extensor tendon injury takes a thorough physical exam, with time spent by the provider to isolate each joint and test the range of motion against resistance. (See “Management of Extensor Tendon Injuries” for more on the exam.)2 The potential impairment that may occur without proper treatment is reason enough to have a low threshold to treat these patients for a tendon injury if there is any doubt in your mind. Even a small discrepancy in your exam may indicate a partial tendon laceration that can progress to a complete laceration if not treated appropriately. Kleinert and Verdan developed a classification system for extensor tendon lacerations that divides the dorsal part of the hand into eight different zones (see Figure 1).3 This classification system is used below as a reference point to provide emergency physicians guidance in treating their next extensor tendon injury.

Extensor Tendon Injuries and Lacerations

Zone I: This zone encompasses the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and the remaining part of the finger distal to the joint. Most commonly, these injuries are closed and require immobilization in hyperextension of the DIP for six to eight weeks and outpatient follow-up with the hand surgeon.4 Besides outpatient follow-up with a hand surgeon, patients are truly responsible for how well these injuries will heal because it’s been shown that compliance with the splint is the biggest factor affecting successful treatment.5

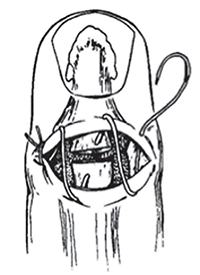

Figure 2. Roll stitch for extensor tendon laceration repair in zones I and II.7

Reprinted with permission from J Emerg Med. 1986;4:217-225.

For open injuries, hand surgeons use another classification method where zone I is split up into four different types.2 For our purposes, we will focus on open injuries with an associated tendon injury that you have identified on exam. If the injury results in physical loss of part of the tendon or significant avulsion of the skin, the surgeon will likely need to take the patient to the operating room for a possible graft, and we should cover them with antibiotics in the ED. However, if there is only loss of tendon continuity, we can suture the tendon back together, splint only the DIP in mild hyperextension, and have the patient follow up as an outpatient with the hand surgeon.6 For these tendon laceration repairs, you may want to use a roll stitch, or dermatotenodesis, that incorporates both the overlying skin and tendon using 4-0 or 5-0 nonabsorbable sutures as detailed in Figure 2.

Zone II: This zone consists of the middle phalanx, and closed injuries can be placed in an extension splint for three to four weeks if there is only minimal weakness on extension. However, significant extensor lag will need to be explored by a hand surgeon on an outpatient basis.8 Open tendon lacerations overlying the middle phalanx can be repaired primarily in the ED using a roll stitch as described above in zone I, splinting the DIP in extension with outpatient follow-up with the hand surgeon.

Any pain on extension or extension lag at the proximal interphalangeal joint on presentation to the ED should raise your suspicion for potential central slip rupture.

Zone III: The most well-known closed injury of zone III is perhaps rupture of the central slip, which results in the commonly tested Boutonniere deformity typically two to three weeks after the injury. Any pain on extension or extension lag at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint on presentation to the ED should raise your suspicion for potential central slip rupture. These patients should be placed in a dorsal or volar splint that keeps the PIP in extension while allowing for full range of motion of the DIP.9 The complexity of the extensor mechanism surrounding the PIP requires the training of an orthopedic surgeon for repair of open lacerations of the tendon. For an extensor tendon laceration identified within the ED, we can suture the overlying laceration, splint the wrist in 30° of extension, the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) in 15° of flexion, and the PIP in the neutral position with outpatient follow-up with a hand surgeon.10

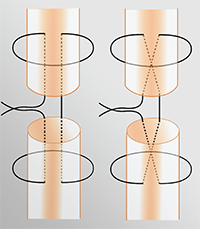

Figure 3. The modified Kessler (left) and modified Bunnell (right) stitches for tendon repair.11

Image Credit: Justin McNamee

Zone IV: Once you start to enter zone IV, the tendons become larger and easier to repair. Fortunately, there are not many instances of closed tendon injuries from zone IV and the more proximal zones. For tendon lacerations that are greater than 50 percent of the tendon, we can repair the tendon with the modified Kessler technique detailed below in the suturing technique section.8 Similar to zone III injuries, these should also be splinted in a volar splint and should follow up with the hand surgeon on an outpatient basis.10

Zone V: This zone is where we frequently encounter the “fight bites” that patients don’t always willingly admit. With the high possibility of subsequent complications, any open injury in this region should be treated as a fight bite until proven otherwise. After extensive irrigation of the wound, we can suture the tendon if possible. However, leave the skin open for hand surgeons to do a delayed closure in their office. This is in addition to placing a splint (wrist in 45° of extension, MCP in 20° of flexion) and starting patients on prophylactic antibiotics, such as Augmentin.5 If patients aren’t going to see the hand surgeon the next day, it may be prudent to have them come back to the ED for a wound check in the next 24 hours.

Using the modified Bunnell technique and 4-0 nonabsorbable sutures, we can repair these lacerations in the ED. Patients can then be splinted (wrist in 30° of extension, MCP neutral, DIP and PIP joints free) and follow up with a hand surgeon.

Zone VI: This zone encompasses the majority of the dorsum of the hand. The broad, well-defined tendons in this area make it, arguably, the easiest tendon repair we can do in the ED. Using the modified Bunnell technique and 4-0 nonabsorbable sutures, we can repair these lacerations in the ED. Patients can then be splinted (wrist in 30° of extension, MCP neutral, DIP and PIP joints free) and follow up with a hand surgeon.10

Zones VII and VIII: Once you have an extensor laceration in the wrist or forearm, the musculotendinous junctions and muscle bellies become more involved, which is outside of the scope of what we can repair in the ED. We should repair the overlying skin and put in a volar splint (wrist in 20° of extension, MCP neutral). Our hand surgeon colleagues are going to need to repair these injuries.10

Tendon-Suturing Techniques

As described above, there are a number of different ways to repair tendon lacerations. Typically, the tendon should be repaired with 4-0 or 5-0 nonabsorbable sutures. Two of the more commonly described repairs are the modified Kessler and modified Bunnell stitches. Figure 3 provides a schematic of the repair.

Modified Kessler Stitch

Modified Bunnell Stitch

Summary

Far too often, we become reliant on our consultants for relatively simple procedures that can be done safely and efficiently in the ED. Figure 4 provides a quick reference for repairing these extensor tendon injuries in the ED; it is assumed that all of these injuries are adequately irrigated and debrided and that the patient’s tetanus status is updated. For the majority of these injuries, you can approximate the overlying skin laceration, splint, and have the patient follow up with the hand surgeon in the next couple of days. These injuries can be repaired as late as one week after the initial injury.9 Instead of waking up the orthopod at 3 a.m. for someone’s drunken stupor–fueled flight through a pane of glass, just take matters into your own hands.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. Justin McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

Dr. Justin McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

References

- Tuncali D, Yavuz N, Terzioglu A, et al. The rate of upper-extremity deep-structure injuries through small penetrating lacerations. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:146-148.

- Griffin M, Hindocha S, Jordan D, et al. Management of extensor tendon injuries. Open Orthop J. 2012;6:36-42.

- Kleinert HE, Verdan C. Report of the Committee on Tendon Injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 1983;8:794-798.

- Anderson D. Mallet finger—management and patient compliance. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:47-48.

- Handoll HH, Vaghela MV. Interventions for treating mallet finger injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:cD004574.

- Carl HD, Forst R, Schaller P. Results of primary extensor tendon repair in relation to the zone of injury and pre-operative outcome estimation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127:115-119.

- Calabro J, Hoidal CR, Susini LM. Extensor tendon repair in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1986;4:217-225. Hanz KR, Saint-Cyr M, Semmler MJ, et al.

- Extensor tendon injuries: acute management and secondary reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:109e-120e.

- Newport ML. Extensor tendon injuries in the hand. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5:59-66.

- Chapter 11: Hand. In: Simon RR, Sherman SC, eds. Emergency Orthopedics. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011:207-211.

- Rosh AJ, Kwon NS, Wilburn JM, et al. Extensor tendon repair. Medscape Web site. Accessed Nov. 16, 2015.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

No Responses to “Emergency Department Management of Extensor Tendon Lacerations”