Rates of electoral participation in the United States continue to rank in the bottom quartile among developed nations.1 Resulting from a number of factors, poor voter turnout has characterized our democracy for decades.2 Can emergency departments help? It might seem like an oddly arranged marriage, but it isn’t.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 06 – June 2020A majority of U.S. voters consistently rank health care as their top policy priority. Simultaneously, voter rolls are shrinking. This suggests that a smaller and smaller group of people are having their voices heard on the direction of health policy.3,4 This is especially troubling for communities of color, those living in poverty, and the young, who are often among the least politically active. COVID-19 has led to the closure of motor vehicle registration offices and other traditional voter registration venues, resulting in plummeting rates of voter registration nationwide. We know that these marginalized patient populations use emergency departments at disproportionately higher rates than the average population because of a lack of access to traditional forms of health care.5 The discrepancies in ED use along the lines of age, race, and socioeconomic demographics represent both a challenge and an opportunity for health care workers as the needs of these populations often extend beyond traditional health care boundaries.

Rising to the Challenge

Many health care professionals have risen to this challenge by broadening their scope of care, engaging more deeply with the social determinants of health, and administering programs that address larger societal issues affecting their patients such as housing, food insecurity, and opioid addiction.6,7 Marginalized patient populations benefit most from these and larger structural changes needed to improve health care delivery systems. But they also have the lowest rates of voter registration.

For example, a disproportionately large share of eligible Americans who were not registered in the 2016 presidential election were low-income citizens and people of color.8 Among eligible voters, 31 percent of African Americans, 43 percent of Hispanics, and just over 43 percent of low-income Americans were not registered to vote in that election.9 Rates among the nation’s young voters are not much better: Only 50 percent of millennials voted in the 2016 election compared to 69 percent of baby boomers and 63 percent of generation X.10

Regardless of party affiliation, policy endorsement, or stance on a given issue, we can all agree that to be pro-democracy we must be pro-participation. Further, most can agree that without claiming their role in our democracy, these groups will never achieve true equity in and risk being politically voiceless.

Previous Efforts

Alister Martin

Health care-based nonpartisan voter registration has worked before. In 2008, the National Association of Community Health Centers ran a voter registration drive in health centers that resulted in more than 18,000 low- and middle-income citizens added to official rolls.11 Another program, conducted in 2012 at two Federally Qualified Health Centers in the Bronx, New York, demonstrated that successful nonpartisan voter registration initiatives can be run out of community health centers without requiring significant physician effort, disrupting clinic workflows, or compromising the patient-doctor relationship.11

Patients have been extremely receptive to nonpartisan voter registration services, with one study finding that 89 percent of individuals approached in a health center waiting room expressed openness to registering to vote.11 These models, specifically directed toward low-acuity patients, are readily adapted to hospital ED waiting rooms.

Another Initiative: VotER

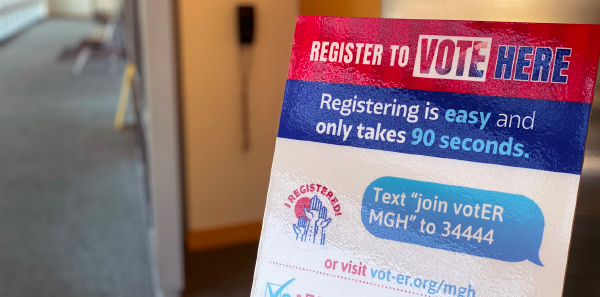

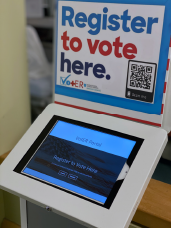

Accordingly, emergency departments across the United States have already begun implementing such voter registration efforts. VotER is one such effort that was founded at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and has since been adopted at more than a dozen emergency departments across the United States. The program uses iPad-based kiosks and posters and discharge paperwork with QR codes in low-acuity emergency department waiting areas to offer patients a convenient, nonpartisan, and optional opportunity to register to vote or check their registration status while waiting.

The platform does not interrupt clinical care or rely on doctors, physician assistants, or nurses providing care to interact with the voter registration process. Patients are guided through the voter registration application on their phone or the iPad-based kiosk in 90 seconds or less. Emergency departments can play a critical role in encouraging patients to register to vote without detracting from the delivery of care using platforms like VotER. Groups like VotER, Patient Voting, and Med Out The Vote are launching the first Civic Health Month in August 2020 to bring a renewed focus to helping patients get to the ballot box, particularly when COVID-19 has made voting in a safe and healthy way a public health issue.

Health care professionals must be concerned with our democracy’s health and mindful of who gets to participate in it. The demographic overlap of patients who lack access to stable care—and therefore use the emergency department at higher rates—and those who historically have low civic engagement affords a natural opportunity to pilot and develop voter registration efforts in the emergency department.

ED-based nonpartisan voter registration via nonintrusive platforms such as VotER is an innovation that can improve our civic system and the well-being of the communities we serve. With an eye toward national elections later this year, emergency departments have the potential to elevate all patient voices in our national dialogue of how to deliver effective, affordable health care in the United States.

Visit www.vot-ER.org to learn more.

Mr. Kusner is 2021 MD candidate at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Mr. Kusner is 2021 MD candidate at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Dr. Dean is an emergency medicine resident at Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Dean is an emergency medicine resident at Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Martin is faculty at the Center for Social Justice and Health Equity at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Dr. Martin is faculty at the Center for Social Justice and Health Equity at Massachusetts General Hospital.

References

- Desliver D. US trails most developed countries in voter turnout. Pew Research Center website. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- Oltman A. Why voter turnout is so low in the United States. Jacobin website. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Americans’ domestic priorities for President Trump and congress in the months leading up to the 2020 election. Politico website. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- KFF health tracking poll. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Augustine JJ. The latest emergency department utilization numbers are in. ACEP Now. 2019;38(10):36.

- Hawryluk M. Why hospitals are getting into the housing business. Medscape website. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Cullen D, Blauch A, Mirth M, et al. Complete eats: summer meals offered by the emergency department for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190201.

- File T. Who votes? Congressional elections and the American electorate: 1978–2014. United States Census Bureau website. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Voting and voter registration as a share of the voter population, by race/ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- File T. Voting in America: a look at the 2016 presidential election. United States Census Bureau website. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Liggett A, Sharma M, Nakamura Y, et al. Results of a voter registration project at 2 family medicine residency clinics in the Bronx, New York. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):466-469.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “Emergency Departments Can Help Get Patients Registered to Vote”

July 1, 2020

NeilI find the idea of voter registration in the ED a little unsettling. I do not think that emergency departments are the right venue for introducing voting registration. As an emergency department, we should be taking care of the sick as our primary challenge. We do this fairly well knowing that HIV testing, domestic abuse, substance abuse, human trafficking, etc falls through the cracks. At times we are struggling to form a safety net for medical health and basic needs. Should we also be a safety net for social health?

I hate to start a slippery slope argument, but I already try to avoid uncomfortable patient conversations whether they start off with: “Can you believe what Trump tweeted today…” versus “Biden had another senior moment…” With these conversations already I put on a smile, nod my head, and try to steer the patient back to determining when their crushing chest pain started.

As an emergency department, we are already been dealing with an incredible amount of social issues in which we struggle to get the resources for let alone voter registration. Lets focus on emergency medical needs, immediate social needs, and then worry about everything else when we get that right.

July 5, 2020

Brian LevyIt’s not our job. It’s also not ACEP’s role to promote this type of initiative.