You are down by five, and there are only three seconds left in the game with 80 yards to go. Do you just take a knee or take a shot down the field with a Hail Mary since there is nothing else to lose? Similar to professional football players, we are professional “resuscitationists.” When it comes to taking care of cardiac arrest patients, we cannot be limited to the playbook of advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS). Occasionally, we, too, have to take a shot with our own version of a Hail Mary. Do we terminate the refractory ventricular fibrillation (VF) coding patient with an end tidal CO2 of 27 mmHg, or is there a new “play” we can try before we pronounce the patient?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 11 – November 2015Case

A 43-year-old father of two presents to the ED via advanced life support (ALS) in cardiac arrest with a presenting rhythm of ventricular fibrillation. According to the transporting paramedics, the patient had a witnessed arrest at home, and the family performed CPR until basic life support (BLS) arrived on the scene. An automated external defibrillator (AED) was immediately placed with “shock advised.” Two shocks were given by BLS prior to ALS arrival. The paramedics were able to intubate the patient and initiate ACLS. They report continued ventricular fibrillation, without return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), from the time of arrival on scene until arrival in the ED. A total of 450 mg amiodarone, 5 mg epinephrine, two ampules of calcium chloride, two ampules of sodium bicarbonate, 100 mg lidocaine, and seven defibrillations were given prior to arrival in the ED. End-tidal CO2 has remained around 25 mmHg with high-quality CPR performed in the prehospital setting. All eyes turn to you upon arrival. “Doc, what else can we do? There are no more steps on the ACLS card but more epinephrine and defibrillations. Should we call it?”

The Opponent: Electrical Storm

Electrical storm (ES) is described in the medical literature as a rapidly clustering ventricular fibrillation that necessitates multiple cardioversions in which conventional antidysrhythmic drug therapy, as recommended by ACLS, fails to convert the patient to a life-sustaining rhythm. ES patients are commonly given antidysrhythmic medications serially while also receiving repeated shocks via an AED. However, despite heroic efforts made by all providers, most ES patients die.1 Refractory arrest secondary to ES is not a new

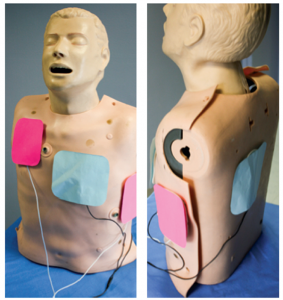

(click for larger image)

Figure 1. Orientation of defibrillation pads for double sequential external defibrillation: anterior-posterior (blue) and anterior-apex (pink).

phenomenon in the medical literature. It has been studied and theorized for well over a decade. Most of the current literature agrees on one concept: an ES activates the sympathetic nervous system and, in turn, leads to a surge of endogenous catecholamines.2 The abundance of endogenous catecholamines is likely the underlying culprit as to why conventional ACLS doesn’t lead to ROSC in the majority of these patients. The ACLS algorithm for VF/ventricular tachycardia (VT) calls for 1 mg epinephrine to be given every three to five minutes; there isn’t an asterisk next to this recommendation for patients in refractory VF arrest stating we should consider holding this medication or trying a different medication in our armamentarium. The addition of exogenous catecholamines in patients in refractory VF arrest or ES seems counterintuitive to what we know about this phenomenon. In fact, a better solution may be to give the patients a class of medications that suppresses the adrenergic surge they are experiencing, namely β-blockers.

The Hail Mary: Esmolol and Double Sequential External Defibrillation

A 2014 study in the journal Resuscitation retrospectively looked at patients in refractory VF arrest and compared those who received standard ACLS therapy against standard therapy followed by esmolol.3 Driver et al defined refractory VF arrest as patients with an initial presenting rhythm of VF or VT who received at least three defibrillation attempts, 3 mg adrenaline, and 300 mg amiodarone and remained in VF cardiac arrest upon arrival in the ED. In this Resuscitation study, a bolus of 500 mcg/kg (0.5 mg/kg) esmolol was administered followed by a continuous infusion of esmolol from 0–100 mcg/kg/min (0–0.1 mg/kg/min) to the study group, while the control group only received medications via the ACLS protocol. Of those in refractory VF arrest who received esmolol, 67 percent had ROSC compared to 32 percent in the standard therapy arm, and 50 percent of the esmolol group survived to discharge with good neurological outcome (CPC score <2) compared to 11 percent in the standard therapy group. While this was a small retrospective study on refractory VF arrest in the ED, the results were in alignment with previous case reports dating back to the 1960s. Furthermore, studies not centered in the ED have used β-blockers for refractory ES, such as the Nademanee et al study in Circulation in 2000 and Miwa et al in 2010.1,3,4 The study results provide a measurable benefit in favor of using β-blockers to counteract the endogenous and exogenous (if given) catecholamine surge theorized to occur during refractory VF arrest. Even though the current evidence for the use of esmolol in refractory VF arrest is far from concrete, it still far exceeds the evidence we have for other chemical agents to use on patients who do not respond to the traditional ACLS antidysrhythmics. However, the use of β-blockers may not be the only option and could possibly be used in combination with another piece of equipment readily available in the ED when the next refractory VF arrest presents to your ED.

With very little downside of employing these interventions in refractory VF arrest patients, ED providers can try this Hail Mary to treat the patient’s electrical storm.

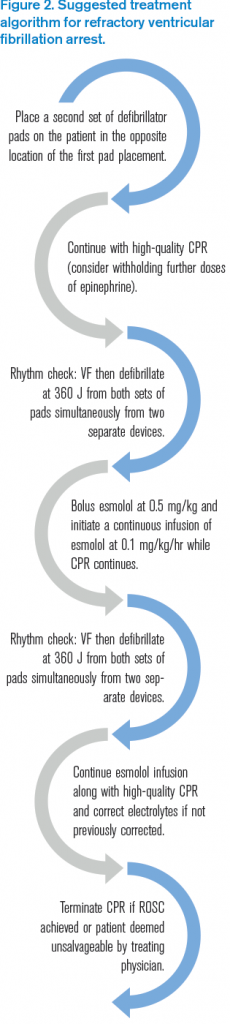

(click for larger image)

Figure 2. Suggested treatment algorithm for refractory ventricular fibrillation arrest.

Defibrillator pads are an easily accessible tool in any ED or ALS vehicle around the world and are placed within seconds of finding a patient in cardiac arrest. There are two universal locations for defibrillator pads to be placed: anterior-posterior or anterior-apex. When we approach a patient in cardiac arrest, the pads are positioned into one of these two positions. Defibrillation remains the mainstay of treatment for VF arrest, but in the rare incidence of ES with refractory VF arrest, the standard ACLS algorithmic approach of increasing voltage through one set of pads may not terminate the dysrhythmia. Hoch et al published a case series in 1994, “Double Sequential External Shocks for Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation,” in which they utilized two sets of external pads placed in both universal pad placement areas to deliver simultaneous shocks to patients who were in

refractory VF unresponsive to standard therapies while in an electrophysiology lab.5 They were able to terminate all the patients in the case series from VF into a perfusing rhythm by delivering double sequential shocks by means of two defibrillators, each with their own electrodes, one set placed anterior-posterior and the other set anterior-apex (see Figure 1). Prior animal studies using double sequential defibrillation suggested the sequential shocks lowered the threshold for defibrillation, improving the odds of terminating the

rhythm. This concept was reintroduced to emergency medicine in 2015 with a prehospital retrospective case series published in Prehospital Emergency Care by Cabañas et al.6 They included 10 patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who had received at least five defibrillation attempts at 360 J along with standard therapy for refractory VF arrest in this case series. A second set of defibrillator pads was placed opposite the first set of pads, and on the next rhythm check, if shock was advised, the shock was delivered at 360 J from the new pad placement. If VF arrest continued, EMS utilized both sets of pads, and shocks were delivered from both machines as synchronized as possible. EMS providers were able to terminate ventricular fibrillation in 70 percent of the patients after double sequential external defibrillation (DSED), and 30 percent achieved ROSC in the field. Unfortunately, none survived to hospital discharge in this case series. However, they were able to gain ROSC in patients who were previously resistant to all other treatment strategies. What if DSED was combined with esmolol to counteract the sympathetic surge? The combination of both treatment strategies that are commonly available to all ED providers may provide some hope for these seemingly helpless cases. With very little downside of employing these interventions in a refractory VF arrest patient, ED providers can try this Hail Mary to treat the patient’s ES.

The New Playbook: Electrical Storm Treatment Algorithm

We suggest employing the following treatment algorithm (see Figure 2) when faced with your next refractory ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest patient. For our algorithm, we define refractory VF arrest as at least 3 mg epinephrine, 300 mg amiodarone (or one dose of another antidysrhythmic), and three attempts of defibrillation with continued ventricular fibrillation.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. Justin McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

Dr. Justin McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

References

- Nademanee K, Taylor R, Bailey WE, et al. Treating electrical storm: sympathetic blockade versus advanced cardiac life support-guided therapy. Circulation. 2000:102(7);742-747.

- Eifling M, Razavi M, Massumi A. The evaluation and management of electrical storm. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011:32(8);111-121.

- Driver BE, Debaty G, Plummer DW, et al. Use of esmolol after failure of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation to treat patients with refractory ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2014:85(10);1337-1341.

- Miwa Y, Ikeda T, Mera H, et al. Effects of landiolol, an ultra-short-acting ß1-selective blocker, on electrical storm refractory to class III antidysrhythmic drugs. Circ J. 2010:74(5);856-863.

- Hoch DH, Batsford WP, Greenberg SM, et al. Double sequential external shocks for refractory ventricular fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994:2;1141-1145.

- Cabañas JG, Myers JB, Williams JG, et al. Double sequential external defibrillation in out-of-hospital refractory ventricular fibrillation: a report of ten cases. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015:19(1);126-130.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

3 Responses to “Emergency Interventions for Treating Cardiac Electrical Storms”

January 13, 2016

Steven SawyerI read this article this past weekend and knew that even though I had never seen a case of refractory Vfib I knew I would shortly. So I was not actually surprised when the 45 year old man brought in cardiac arrest had Vfib for which he had received two doses of epi and three shocks by ems. An LMA was in place and while cpr continued I had to wait to see the monitor. During a change in compression hands I saw the fine vfib and delivered another defib with epi and amiodarone to no avail. During the next cycle I had a chance to brief the team on the article I had read and get a copy so we could check the dose of Esmolol while maxing the amiodarone and applying the 5th shock. However, it turned out that we had no Esmolol in the ED. At this point it was 30 since being found down. I set the two defibrillators and performed the double sequential external defibrillation which initially converted from fine vfib to asystole After additional CPR and an additional attempt the code was called. It turned out that the pt had initially been over come with carbon monoxide which lead directly to his cardiac dysrhythmia. Had I known this I may have elected to remove the LMA and intubate for better oxygen support. But overall my team was fast and compliant with the strange instructions I gave. It just didn’t work this time.

March 7, 2017

günther krumpl0–100 mcg/kg/hr (0–0.1 mg/kg/hr)

Please correct the text in the publication to the right dose which should be

0-100 mcg/kg/min.

In addition I want to mention that 0 in 0-100 makes no sense, the starting dose of esmolol is 50. So it should say 50-100 …

April 14, 2017

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you, the article has been updated to indicate mcg/kg/min instead of mcg/kg/hr.