Emergency medicine (EM) has evolved over time and has long passed a crossroads where previously unachievable capabilities should be celebrated and shared. Emergency physicians have become leaders in achieving cost efficiency in health care, predominantly through implementation of new processes and research findings, enabling us to achieve significant financial savings.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 07 – July 2023Emergency physicians have earned the right to “re-brand” ourselves as indispensable, money-saving change agents in the health care enterprise.

Of course, the bill for any episode of emergency department (ED) care can be substantial, exceeding the billed charges for equivalent care provided in some primary care offices. Thus, the idea that we are leaders at achieving cost savings may at first seem counterintuitive.

However, such a view overlooks two critical facts. First, much of the care we provide could not be provided in an office. Second, as cited above, we have implemented research findings to decrease costs of care safely, via processes that did not exist at the time the American Board of Emergency Medicine became recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties in 1979, or even at the time I entered emergency-medicine residency training in 1986.

After convincing ourselves that we save our systems large sums of money, we need to educate our critics. We don’t deserve the recurrent blame and scorn from individuals who shape public opinion, including some politicians and journalists, who repeatedly focus on the charges accrued for ED care, with only passing acknowledgement of the critical role we all play as the nation’s 24/7/365 resource for medical care for all who present at our doors, without regard for their ability to pay.

Here are some illustrative examples demonstrating how emergency physicians save our system money every day, compared to status quo of the late 1970s and early 1980s: Formerly, nearly all acute pyelonephritis patients were admitted for several days of intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy. Now, many acute pyelonephritis patients receive an IV antibiotic, analgesia, and an antiemetic in the ED. Once patients demonstrate they can keep oral liquids down, most are prescribed oral antibiotics, analgesics and antiemetics, and discharged. Acute pyelonephritis has become a disease for which outpatient management is often feasible and appropriate.1

Formerly, most patients with Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) were admitted for several days of IV antibiotics, under the now-disproven dogma that IV antibiotics decreased the scarring of the Fallopian tubes and enhanced the patient’s future fertility. Now, many PID patients are treated and released after ED administration of appropriate antibiotics to eradicate possible infection by Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis, often with added treatment for anaerobic microbes. Female upper genital tract disease has been transformed to a disease for which outpatient management is often feasible and appropriate.2

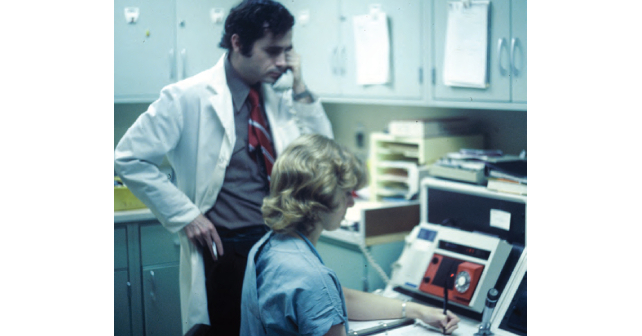

Technological changes have helped emergency physicians become more efficient.

Formerly, all patients diagnosed with the venous thromboembolic (VTE) diseases of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or acute pulmonary embolism (PE) were admitted for several days of inpatient care to enable therapy with intravenous heparin as a bridge to oral warfarin. Warfarin pills are inexpensive, but the associated hospital care is not. Warfarin is a drug highly prone to drug-drug and drug-food interactions.3 Further, warfarin dosing requires regular monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR), which is both a cost and an inconvenience to patients. We can now safely treat most DVT patients as outpatients by prescribing direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as Factor Xa Inhibitors. Subsequently, we also learned that PE patients without hypoxia or evidence of right heart failure can safely be discharged with DOAC prescriptions. DVT and PE have been transformed to diseases for which outpatient management is feasible and appropriate.4

Formerly, chest pain patients without an S-T Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction (STEMI), whose pain was suspected to be cardiac in nature, became inpatients for sequential monitoring of their lactate dehydrogenase and creatine kinase isozyme profiles. This process required at least a full day. Now, for selected patients, emergency physicians can leverage low and non-rising high sensitivity troponin values and a low HEART score (composed of history, ECG, age, risk factors, and troponin level) to implement outpatient follow-up plans safely, within a few hours.5

Patients with acute ischemic strokes, STEMIs, and trauma, as well as many other diagnoses, have their workup largely completed, and even sometimes definitive therapy executed, before they leave the emergency department, rather than requiring inpatient units. We could do even better if only our patients would permit it. We already know how to apply validated and highly reliable clinical decision rules (CDR) such as the Ottawa Ankle Rules, the Ottawa Knee Rules, the NEXUS and Canadian C Spine rules and the PECARN (for children) and Canadian Head CT (for adults) rules.6–11 All perform with high accuracy and validity. However, we know that patients often expect radiographs that these CDRs would establish as contraindicated.

Our collective experience is that a significantly long time is required to explain these CDRs to patients, so it becomes more cost- and time-effective simply to obtain the non-indicated imaging. Emergency medicine should advocate directly to patients to allow doctors to implement these CDRs more efficiently by applying effective bedside “plug and play” teaching tools and explaining CDRs. Such resources could dissuade patients from false beliefs and persuade them that omission of the contraindicated radiographs or tests represents appropriate care. This would both save money and shorten the patient’s ED stay. Added benefit would accrue when a pediatric patient avoids CT images, thereby decreasing the potential risk for a subsequent cancer.12

To enable this vision and further enhance our role toward cost savings will require emergency medicine researchers to complement validated CDRs with the creation, testing and validation of accurate and persuasive patient-education tools, sufficient to dissuade most patients from dogmatic and erroneous beliefs regarding imaging. Emergency physicians have exploded incorrect dogmas before. For instance, consider the previous dogmatic belief that no abdominal-pain patient can be administered an opiate until they have been examined by a surgeon.13 Hopefully, patients’ beliefs regarding radiographs can also become consigned to the dustbin of history.

In re-branding ourselves, we should also work to explode other myths that plague us, by refuting certain misleading beliefs that cause the public to conclude wrongly that ED care is a larger source of health care expenditures than is the case.

Brian Zink captured a wonderful initial vision statement for our specialty with the title of his book, “Anyone, Anything, Anytime,” which documented the history of our specialty. In 2023 we must move beyond that title. Emergency physicians help not only save lives, but also save significant sums of money, 24/7/365. Might I suggest: Emergency Medicine: Saving lives, but also dollars, with our quick, efficient, and effective care.

Dr. Gaddis is a “PGY-37” who has stepped away from full-time employment after a 32-year full-time career in academic emergency medicine, and now works a limited number of shifts in a rural Critical Access hospital in Missouri. He also currently serves as a professor of Biomedical and Health Informatics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, and enjoys exploring contrarian views of issues that impact the specialty of emergency medicine.

Dr. Gaddis is a “PGY-37” who has stepped away from full-time employment after a 32-year full-time career in academic emergency medicine, and now works a limited number of shifts in a rural Critical Access hospital in Missouri. He also currently serves as a professor of Biomedical and Health Informatics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, and enjoys exploring contrarian views of issues that impact the specialty of emergency medicine.

References

- Herness J, Buttolph A, Hammer NC. Acute pyelonephritis in adults. A review. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:173-180.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). CDC website: Sexually Transmitted Disease Guidelines 2021. Updated September 21, 2022. Accessed June 10, 2023.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Warfarin side effects. Watch for interactions. The Mayo Clinic website. February 22, 2022. Accessed June 10, 2023.

- Stubblefield WB, Kline JA. Outpatient treatment of emergency department patients diagnosed with venous thromboembolism. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(Supp 1):11-19.

- Gulati M, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:e187-e285.

- Stiell IG, et al. Decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Refinement and prospective validation. JAMA. 1993; 269:1127-32.

- Stiell IG, et al. Prospective validation of a decision rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. JAMA. 1996;275:611-5.

- Hoffman JR, et al. Validity of a set of clinical criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in patients with blunt trauma. National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:94-9.

- Stiell IG, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2510-8.

- Schonfeld D, et al. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network head injury clinical prediction rules are reliable in practice. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:427-31.

- Stiell IG, et al. Comparison of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005;294:1511-8.

- Sheppard JP, et al. Risk of brain tumor induction from pediatric head CT procedures. A systematic literature review. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2018;6:1-7.

- Brewster GS, Herbert ME, Hoffman JR. Medical myth: Analgesia should not be given to patients with an acute abdomen because it obscures the diagnosis. West J Med. 2000;172:209-10.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Emergency Medicine Deserves to “Re-Brand” Itself as a Cost Saver”