For decades, the concepts of democracy and democratic group practice have been held as the standard to strive for in emergency medicine. As democracy is akin to motherhood and apple pie, these concepts are accepted today, perhaps, just as they were decades ago. However, with the evolving landscape of health care, is it time to revisit these concepts? Is democracy a group structure or an ideal? Democracy can provide an opportunity to participate in group decisions and control one’s own destiny (to a certain extent), but democracy means that, on occasion, you may not get what you want if you are in the minority. Is democracy truly what emergency physicians want, or has fair and equitable treatment become the practical definition of “democracy”? In Part 2 of this three-part series, EM leaders from different walks of life will weigh in on the following questions. Read Part 1.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 11 – November 2015Moderator

Ricardo Martinez, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer for North Highland Worldwide Consulting and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Emory University in Atlanta

Ricardo Martinez, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer for North Highland Worldwide Consulting and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Emory University in Atlanta

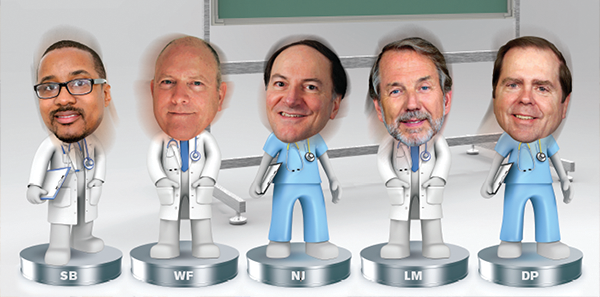

Participants

Savoy Brummer, MD, FACEP, vice president of practice development at CEP America in Belleville, Illinois, and chair of the ACEP Democratic Group Section

Wesley Fields, MD, FACEP, past chair and the most senior member of the Board of Directors of CEP America in Emeryville, California

Nicholas J. Jouriles, MD, FACEP, president of General Emergency Medical Specialist Incorporated, a single-hospital group in Akron, Ohio

Lynn Massingale, MD, FACEP, executive chairman of TeamHealth in Knoxville, Tennessee

Dighton C. Packard, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer of EmCare in Dallas

RM: Does being a democratic group have associated with it both positive and negative obligations and responsibilities that we don’t talk about much?

NJ: We’re a group that’s been around for almost 40 years, we staff one health system, everyone has a vote, and everyone is treated equally. This conversation has been brilliant because I think everyone has brought up the exact same issues that really are facing the specialty and the people involved. I do believe that a small group can have the chops to do things, and in our group, everyone pitches in. Everyone doesn’t do the exact same thing, but everyone does a comparable amount of work, just different work. I get tasked to run the show and my program director gets tasked for most of the academics because we do staff one of the oldest residency programs in the world. We don’t get treated seriously because I can’t walk into a payer the same way Lynn, Dighton, or Wes can; they can get a lot more leverage out of it than I can. I pretty much go in and do as I’m told, so that’s a fault for the system. There are certain things that, for a democratic group, make no sense whatsoever. An example from our particular group is we once had a 30-minute discussion about what color scrubs we were going to wear because everyone had to vote. That’s a complete waste of time. We’re also facing something that is being attributed to being generational, and I don’t know if that’s fair or not, but we’re seeing more and more people graduating from medical school and residencies who have no interest in doing what Wes, Dighton, Lynn, and I do every day. They want to see patients and go home. They don’t want to have ownership. They just want to get a paycheck, and that’s neither good nor bad, but it makes it very difficult for a group like mine that relies on people to have individual incentives to step up to the plate to work the extra shifts, to write a check to cover the capital costs. People aren’t interested in doing that, and I think that is more of a danger than anything to the democratic group than anything else. I think we’re facing a generational change at the same time that the regulations, obligations, and accountability, as outlined by Lynn, are there, so it’s a mismatch that’s going to make this particular model an endangered species.

SB: There’s a very large difference among democratic groups. They don’t all fit in one shape or size, and it is a very diversified space, just like how groups that aren’t democratic are extremely different in terms of structure, resources, and location. I think that it would be a shortcoming of our discussion to just talk about the smaller, independent democratic practices that still exist because there are regional and national democratic practices that also exist. I think they address some of the very real challenges that Lynn has alluded to. I think that practice integration and meeting the standards for our hospitals in terms of population health are very difficult if you are a one service line, single, independent institution. However, democratic organizations have greatly evolved into various practice lines so that they can meet the challenges of the current health care environment and continue with their structure. Being treated fairly is an admirable starting point for many young emergency medicine doctors, but equity is a prized possession for emergency physicians. If you’re able to maintain your equity and diversify your deliverables so that you can meet the expectations of your hospital, well, that’s great, but there are significant pressures that are forcing the smaller democratic and nondemocratic independent practices to look at other options. However, I think that many of these single, independent places believe that being democratic is the problem when it’s really a lack of diversification and economies of scale that are the problem, and we shouldn’t mix those two together. There are plenty of single, independent groups that are in a good place and have great relationships that can keep on going for “X” period of time. I think that eventually the health care environment will show its cards, and you will see, from different regions of the country, those pressures will either make these independent democratic practices look for other options or be able to remain viable.

NJ: I agree with that. It is a matter of scale more than anything else. I think docs are smart enough that they can run a business if they have to, but many are choosing not to, unless you’re big enough to be able to compete and win.

RM: What are the pros and cons of the democratic group versus nondemocratic group as we see the market consolidate, not only to take on risk but also to move toward population health? Do we see pros and cons of the different models?

WF: One of the long-running experiments with CEP America is whether or not a group that’s equity-based and where ownership is really strategic in terms of delivering high-quality clinical services, integrating well, expanding across practice lines or medical specialties and across different regions and markets can succeed while operating privately and not accepting outside investment or being tied to short-term financial demands or requirements in order to access capital markets. For us, a culture of ownership, a culture of caring, and the long-term commitment to satisfying careers essentially mean that each of our partners is also our investment banker. What we believe to be important is that this allows us to make strategic plans that are long term in nature, and we’re not at the mercy of a culture, which you actually see in many small democratic groups, where it’s me here and now, “What’s my hourly? What’s my paycheck? What’s my bonus this year?” I think the way individual groups, with all kinds of structures, think about ownership, equity, and investment within each other and their community is really crucial. I think that’s what Nick is pointing out and, in his own way, Lynn as well. Our belief in CEP is that it’s not so much that we’re a democracy that makes us likely to be one of those winners that Lynn was talking about but that we have the ability to think long term and to be able to operate privately and still achieve scale, have success with integration, and have our model make as much sense for anesthesiologists or physicians practicing in nursing homes as it does for PIT doctors in the emergency department. We think all those things are important; we see it as an incredible challenge, and it gets tougher every day. One of the features of many successful long-term investors—Warren Buffett is a classic example—is the ability to be patient, methodical, principled, and think long term. One of my favorite quotes from Warren is, “If you want to get rich, it’s better if you’re not in a hurry.” The other I’ll throw in is that I still think in many ways Winston Churchill was right when he said, “Democracy is the worst form of governance possible except for all the others.” I think partners like Savoy and I, with all the challenges we face inside CEP, believe that. Every day is a challenge for us to demonstrate that it’s still true that democracy is the best way forward.

I think that eventually the health care environment will show its cards, and you will see, from different regions of the country, those pressures will either make these independent democratic practices look for other options or be able to remain viable. —Savoy Brummer, MD, FACEP

One of the features of many successful long-term investors—Warren Buffett is a classic example—is the ability to be patient, methodical, principled, and think long term. —Wesley Fields, MD, FACEP

Perfection is in the eye of the beholder. What works for one graduate is inappropriate for another, and this idealized vision that you’re going to get to vote on everything or get 100 percent bonus every single day just doesn’t exist. —Nicholas J. Jouriles, MD, FACEP

LM: Investing can mean a lot of things. Investing can mean spending money on physician leadership development. Investment can mean spending money on risk-management programs that aren’t really going to save you money until one, two, or three years down the road. Investment could be IT investments, which increasingly all of us are having to make or are choosing to make because we don’t want to have to wait for the hospital or the payer to tell us how well or how badly we’re doing in a particular area. I think groups of many different kinds can make those investments. Envision and TeamHealth are both public companies, and sometimes there may be the perspective that it must be all about this quarter. Well, I can tell you, and I suspect Dighton can tell you, we invest a boatload of money that’s not going to generate anything except a negative in a given quarter in service of having a better organization for the long term. I’m confident that groups like CEP make those same kinds of investments in people, education, risk management, and IT. I suspect none of us enjoys some of those investments in terms of the costs, especially in IT. It’s hard even for a highly motivated, smaller democratic group to make those same investments. Perhaps that’s why some of those smaller democratic groups are coming together and coalescing in some interesting ways. There are a lot of issues here about democracy and scale. I just don’t think even a democratic group can afford not to invest in somebody in that group spending a disproportionate amount of time thinking about the business side of the business. One of the sisters here, years ago when the sisters were actually running the hospital, said to me, “There is no mission if there is no money,” and it’s OK to talk about the money sometimes. Whether it’s managed care contracting or investing in IT, every one of us has to be thinking about making some of those long-term investments, and it’s just harder in some places than others.

NJ: I think it’s ironic that we’re all saying many similar things. Wes, sorry we’re not as smart as you out there on the West Coast. You eloquently quote smart people; we quote rock and roll. To me, it’s, “You can’t always get what you want.” Even with my residents, I talked to them just this morning about getting jobs when they finish in June, and everyone has this idealized vision that they have to get everything exactly perfect. The reality is it doesn’t exist. Perfection is in the eye of the beholder. What works for one graduate is inappropriate for another, and this idealized vision that you’re going to get to vote on everything or get 100 percent bonus every single day just doesn’t exist. There are a lot of requirements regulatory and otherwise now, much more than when I started. The practice is much more complex than it ever was, and it’s not going in the other direction; it’s going to get even worse. You have to spend an inordinate amount of time dealing with non–patient care issues to get the practice working, and a lot of people just don’t want to do that. They have to come to the realization that you’re not going to get everything. There are going to be trade-offs in your practice, and we need to accept that.

SB: I would agree. I think in most democratic groups there are fiduciary duties to respect the needs of the individual physician, but there are also duties to respect the needs and desires of the aggregate, and that can manifest itself in different ways. But ultimately, I think that a democratic practice attracts a special type of personality and a special type of physician. Clearly, there are sacrifices, and as long as we can define a democratic model and define the option that these young resident have when they go out into the workforce so that they truly understand what not only an idealized view of a democratic practice is but give actual working examples that are out there, I think that they can weigh all of the risks and benefits on their own.

RM: How we’re getting paid is changing, and we’ve not touched on that. The transition from fee-for-service toward a value-based system does take investments, changing organizations, growth of IT that can support it, and the ability to take on risk. What we’re seeing are a lot of independent practices in other specialties rolling up and forming new organizations, and they’re having to give up some of their autonomy as small, independent practices in order to gain market position in order to be able to take on risk. They’re also partnering with nonphysicians. They’re partnering with health systems to create new entities. How do we see that transition affecting what might be the best approach to organizing in emergency medicine? Do we continue to say we’re going to be ourselves, or do we move forward and join these consolidations? What do you see happening there, and how will that affect autonomy and democracy?

WF: That’s a really fascinating topic. Jeff Selevan is a good friend of mine, and he recently retired as the CFO of Southern California Permanente, which in its own right is a democratic partnership. It has 8.5 million members just in California. Jeff has said that consolidation is not integration, and I really, really think that’s true. One of the things that we will agree on is that we see a better future for health care and a better shot at achieving the triple aim with physician-driven cultures of care. I think the most important spirit of democracy, if it still matters, is one that results in more effective teams and engagement with physicians and other providers. I think one of the things we probably all believe is that practice models that aren’t pro integration, that aren’t willing to integrate and aren’t willing to change, probably won’t succeed. One of the dangers of democracy, especially on a smaller scale, is that if all you’re concerned about is the rights of individual partners or providers, and all they’re concerned about is voting their own self interest, you’re not necessarily going to get there.

Now, those of us that are large organizations, we believe in economies of scale, but most of us acknowledge that there are diseconomies of scale [forces that cause larger firms and governments to produce goods and services at increased per-unit costs], and there are some bureaucracies that all of us would like not to have. —Lynn Massingale, MD, FACEP

SB: The irony here is that by having so much consolidation we’re going to end up with a bunch of big practices. Not all of them are going to succeed, and some are going to have so much bureaucracy, they’re actually going to fail because of their size. I think what’s going to happen in the industry is we’re going to have a whole bunch of consolidations. We’re going to have a few really, really big people doing really well; a bunch of people in the middle not doing well; and some smaller groups that were actually small enough, facile enough, and nimble enough that they can outmaneuver everyone. You either have enough size that you can keep your costs down, or you’re going to be fast enough to take care of the patients quickly and efficiently so that you can make money that way. The people in the middle are going to do terrible.

LM: To that point, Jack Welch famously took the position during his tenure at GE that if he couldn’t be number one or number two in a particular market, then he didn’t need to be in that market. He later said that had been a serious error, that he had missed lots of opportunities to have lots of good businesses and divisions of GE that could have been very, very successful and very competitive. Now, those of us that are large organizations, we believe in economies of scale, but most of us acknowledge that there are diseconomies of scale [forces that cause larger firms and governments to produce goods and services at increased per-unit costs], and there are some bureaucracies that all of us would like not to have. We obviously think that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages, and I don’t think any of us—at least I surely don’t—think that this is the only way to do it. I think what you said is right: there are going to be lots of ways to skin a cat. But I don’t think you can do just what you always did and have your head in the sand about the changes that are occurring around us and still succeed. Whether you’re a single hospital group, regional group, democratic group, or a publically traded group, you just can’t be complacent about that.

NJ: And the key to that is you have to invest the time and energy and the resources to make those changes. If you decide not to make that investment, you’re going to lose.

No Responses to “Emergency Medicine Leaders Discuss How Democratic Groups Manage Scale, Consolidation”