For decades, the concepts of democracy and democratic group practice have been held as the standard to strive for in emergency medicine. As democracy is akin to motherhood and apple pie, these concepts are accepted today, perhaps, just as they were decades ago. However, with the evolving landscape of health care, is it time to revisit these concepts? Is democracy a group structure or an ideal? Democracy can provide an opportunity to participate in group decisions and control one’s own destiny (to a certain extent), but democracy means that, on occasion, you may not get what you want if you are in the minority. Is democracy truly what emergency physicians want, or has fair and equitable treatment become the practical definition of “democracy”? In this three-part series, EM leaders from different walks of life will weigh in on the following questions. Read Part 2.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 10 – October 2015—Kevin M. Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP

Moderator

Ricardo Martinez, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer for North Highland Worldwide Consulting and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Emory University in Atlanta

Ricardo Martinez, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer for North Highland Worldwide Consulting and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Emory University in Atlanta

Participants

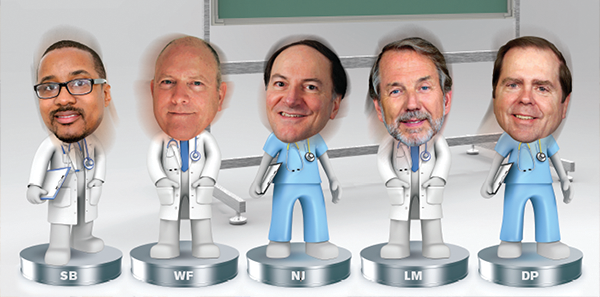

Savoy Brummer, MD, FACEP, vice president of practice development at CEP America in Belleville, Illinois, and chair of the ACEP Democratic Group Section

Wesley Fields, MD, FACEP, past chair and the most senior member of the Board of Directors of CEP America in Emeryville, California

Nicholas J. Jouriles, MD, FACEP, president of General Emergency Medical Specialist Incorporated, a single-hospital group in Akron, Ohio

Lynn Massingale, MD, FACEP, executive chairman of TeamHealth in Knoxville, Tennessee

Dighton C. Packard, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer of EmCare in Dallas

RM: So let me go with our first question: what is the definition of “democracy”?

WF: Well, I think this is very perspective-driven, and I’ll start with one that I don’t necessarily subscribe to but I think is common with emergency medicine, in particular in a lot of residency programs, and probably supported by the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. Some folks in emergency medicine believe in an ideal or aspiration that’s based partly on the idea that emergency medicine can be practiced privately in the same sense you can have a private practice, such as dermatology or something else that’s not hospital-based, and that beyond that, all rights and privileges that can be assigned to other medical specialties need to be attributable and available for emergency physicians as well. I think that some folks believe that to be an attainable goal or a reality in our present world, but all of us have real-life experiences that demonstrate how tough it is to get close to that ideal.

NJ: Definition, I don’t know. Go to the dictionary, and 1a you measure with a ruler. I agree completely that everyone has a different perspective, and everyone throws out meanings, and everyone has a different definition. I think the basic concept is, are you treated fairly? And “fairly” is situational. What’s fair in one group is not fair in another. I think as long as each individual member is treated fairly within their own group, that’s what should count.

SB: I think that coming from our section’s perspective, ACEP was fairly clear in how they defined democratic groups. They had a policy that was adopted back in ’08 and reaffirmed in 2014. I believe EM groups are defined by their governing body that is subject to change by fair and transparent elections that embody a one-vote, one-person structure and philosophy or representative vote recognizing equity, ownership, or seniority within the group. This governing body or electorate will control the finances and the decision making in the group. Again, it’s a longer policy, but those are the primary points. How do you measure democracy? I think that is reflective in at least some of the things that our Board of Directors tried to establish. They’re not true metrics, but it says that all the members should have a right to petition the governing body for their grievances, access to a fair due-process procedure, freedom to speak within the business confines of the group in a nondisruptive manner that should be exercised without fear, and lastly, an equal and realistic ownership opportunity within their group. Alluding to some of the comments by the last two folks, several of those elements are very much about fairness—due process, how you’re treated.

RM: Let’s keep going around for other insights in terms of how you might measure that. Lynn, you want to jump in?

LM: I guess to the typical person, I think when you ask what democracy is, it mostly means one person equals one vote on all material things. In reality, most democracy is one person, one vote, but in general, it’s one person, one vote on things that come to a vote, not necessarily on all things that matter to that entity or organization or group. I wouldn’t even quarrel that the best definition of democracy is one person equals one vote on everything that matters. To me, the question is, is that the best or is that even a common model in emergency medicine today? In addition, I would say it’s neither common nor best if that precise definition is actually the definition.

RM: You want to expand on that?

LM: Well, first off, I don’t think there are many groups that meet all the criteria that Savoy just recited. I’m not quarreling with them at all. I just don’t think there are many groups like that in any specialty and certainly not in emergency medicine. Second, with the pace of change and the challenges that face all of us these days, I just respectfully question whether it’s a practical model for “running a railroad,” if you will. I think if you take that to its logical extreme, it means that each person has equal responsibility for everything that the organization does, legally, financially, etc. By and large in groups, even the ones that have one person, one vote, my experience has been that the work is never equal and the level of commitment to accountability and responsibility is never equal. There are pretty big differences even within groups that are largely or entirely democratic by even that strict definition.

RM: Great. Who hasn’t weighed in here? Dighton?

DP: I think we need to be definitive about what exactly we’re trying to define here because Savoy clearly enunciated what ACEP’s policy is and that’s what a democratic group is. What does “democracy” mean? We may be talking about two different definitions there. I think I would lean more toward, when you say what does “democracy” mean, what it means to individual physicians. When a doc is working in the emergency department, does he feel or she feel like that she’s being treated fair or equitably? Does she have a voice about what goes on in that department? I feel like, more often than not, that’s what they would define as “democracy” rather than “I have ownership and I’m responsible for everything that we do.” What I’m finding is—and I freely admit that I’m not sure that I’m the oldest person on the call, but some of us have been around a lot longer than others—that I’ve seen this change. I know that when we started out, we very much wanted to have our own shop. We wanted an independent practice within the hospital. I think Wes, and to some extent Lynn, has already said that this is becoming intensely difficult to do, just like we’ve seen many of our fellow independent practitioners outside the hospital coalesce together in large groups for very obvious reasons to them. I think that’s what’s happening to hospital-based groups as well. It’s becoming very difficult to

“Fairly” is situational. What’s fair in one group is not fair in another. I think as long as each individual member is treated fairly within their own group, that’s what should count. —Nicholas J. Jouriles, MD, FACEP

Clearly there is confusion, and many times that type of confusion is present because there are groups that are trying to confuse the term for their own purposes. It has been very, very clearly stated, by both AAEM and ACEP, what the tenants of a democratic group are about. —Savoy Brummer, MD, FACEP

The important question is whether or not the democratic practice model is clearly the best way to deliver care on behalf of populations or if it’s really a boutique kind of activity that can only happen in increasingly rare circumstances. —Wesley Fields, MD, FACEP

practice independently. The regulatory, bureaucratic requirements and hospital-based requirements are making it much more difficult to do that. Even if one was to agree that it was ideal, one hospital, one group, purely democratic practice, according to ACEP’s definition, I think it’s very, very difficult to accomplish that in today’s world. Much less, when you deal with systems of hospitals, then it becomes even more complicated. Democratic group, well, ACEP has it defined it. I guess I could argue with one or two words, but I think it’s more important to me what my doctors feel about it. My doctors feel that they’re being treated fairly both by my group and by the hospital. To some extent, I see that as part of my job to make sure that happens.

RM: You raise a good point. Is it really about specific things, or is it really about the definition of “democracy”? I can tell you, when I ran the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, I often told my staff that they were confusing our organization with a democracy. Somebody had to be in charge, and we had to have certain roles and responsibilities well-defined in order for us to execute as a team. We’re taught in medicine that it’s about independence and autonomy, but we see in the landscape a big move toward organizational change that’s creating much greater focus on teams. With teams, you have to give a little bit of something to become part of something bigger. That’s why this is a good time to help define what the characteristics of democracy are versus our next question: is it something specific, or is it really more of an ideal? I’ve heard the group talk about having a voice at the table, being able to participate, that sort of thing. So do we think (I’ll go to the third question) there’s some confusion, bouncing off of Dighton’s comment, of exactly what democracy should be about? I’ve heard it’s changing.

SB: As it relates to a democracy, even in our national governance, there are different, obvious forms, and here in the United States, we are the gold standard of a democratic system, but not everyone in our country votes on every issue every time. The ability for an organization, or for a nation, to proceed with effective governance is many times in the form of a representative democracy. There’s nowhere in ACEP that describes a democratic organization or even the basis of democracy within a group as a one-site location. When we talk about getting confused, clearly there is confusion, and many times that type of confusion is present because there are groups that are trying to confuse the term for their own purposes. It has been very, very clearly stated, by both AAEM and ACEP, what the tenants of a democratic group are about.

My doctors feel that they’re being treated fairly both by my group and by the hospital. To some extent, I see that as part of my job to make sure that happens. —Dighton C. Packard, MD, FACEP

WF: I’m pretty sure ACEP can validate this for me, but I think that most of us that deal with hospitals and hospital-based systems see that there’s a pretty strong trend in recent years that there are more emergency physicians directly employed, either by hospitals or related entities, than there are people practicing in democratic groups of any size. It’s obviously not what we’re talking about, but I think how important this is or how relevant this is depends on how common or prevalent this practice model is. My sense is that it’s a little bit of an endangered species for the reasons that Dighton suggested, and I think folks that read ACEP Now probably need to know what the facts are.

SB: We have 15 million visits that are seen in our democratic section. If you take a cross section of the groups that define themselves as democratic practices, which are within that section, 15 million visits is not a small number, and there are plenty out there that are just independent and don’t come to the section meetings. So it’s a much larger number than one would expect.

WF: I think it raises a question, not from the point of view of practitioners of emergency medicine but from the point of view of payers and executives in hospital systems and other people that are interested in the triple aim. I think that what they want to know is whether or not democratic group structures actually add value to the quality of care on behalf of patients and population. I think that’s becoming the market test and also the government challenge coming at us from both employers and payers and people that run the federal programs. The important question is whether or not the democratic practice model is clearly the best way to deliver care on behalf of populations or if it’s really a boutique kind of activity that can only happen in increasingly rare circumstances.

By and large in groups, even the ones that have one person, one vote, my experience has been that the work is never equal and the level of commitment to accountability and responsibility is never equal. —Lynn Massingale, MD, FACEP

LM: I think this will be on point to what Wes just said. My analogy: A friend of mine runs a large, large, large chain of nursing homes. I was talking to him the other day, and he was telling me about how his average length of stay was going down dramatically and how his census was going up and yet his total occupancy was going down. I thought about all three of those data points. Those are metrics that in the past no one would have ever associated with a nursing home except occupancy percentage. No one talked about length of stay in a nursing home in the past. What’s happening with payment reform, with demonstration projects, with others putting somebody at risk, somebody who chooses to be at risk, working with an [accountable care organization] or other entity, etc., focusing on the admission and the 90-day post-acute after the admission, the simple fact is that people are trying to get patients in and out of nursing homes quickly, not just parking them there indefinitely. They’re aggressively managing the therapy they receive. It’s an example of an industry that’s being absolutely transformed, not willingly but transformed by force, outside forces, into a whole new set of behaviors that they have no control of. They have no control of the forces that are acting on them. They’re simply reacting to those forces and those forces being the assumption of risk by some entity, like an ACO. Increasingly, I think all of us in emergency medicine, and our colleagues in hospital medicine, are feeling those same pressures. When you think about the IT commitment and the organizational change that has to take place to make the group ready to accept risk, or be part of risk and reward, it’s just so hard to do that if you’re spending almost all your work time on clinical care. Somebody has to spend a fair amount of time on the administrative piece and a fair amount of money on the administrative piece. I know when we first started, one of the doctors in my group said, “Look, I appreciate the fact that you want to spend time on the business stuff, but it doesn’t really mean a damn thing to me, and I don’t think I should have to pay anything for the time you spend administratively.” Most groups feel like that. There are big groups, there are democratic groups that do have people who spend a lot of administrative time, so I’m not saying it’s all or none. But it’s very hard for a group to do that if, in fact, there’s an expectation that everyone has an equal vote, everyone’s going to do equal work, everyone’s going to write a check for capital expenditure for IT, etc. It’s just gotten so complicated. The good news is everyone on this call spends all day, every day with a group of people who are really, really smart. In my case, most of them are smarter than me, or all of them are smarter than me, but we all spend time around smart people. It’s not that doctors in emergency medicine are not capable of doing that. Our experience is more and more they don’t want to do that. The ones who want to do that can find a place to do that in any group, either in a small group or midsize group or a big, a democratic group or a group like ours. If you want to do that work, you can find it, but if you don’t want to do that work, which is what we find more and more is the case, then you have to figure out where you want to be. And for me, the most important question for a doctor, any doctor, isn’t, is it a democratic group or not, but is it a group that’s going to win? Is it a group that’s going to survive? That’s number one. And is it a group that’s going to win in a rapidly changing health care environment that requires all of us to be and do things that we were not and could not do yesterday or last week? That to me is the better question. Not is TeamHealth a democratic group or not because we aren’t. The question is, are we going to win or not? The question is, is CEP going to win or not? The question is, is the Akron General group going to win or not? And if you are, if that group has the chops and the commitment to win in that changing environment, then I think good doctors can find a great place in any of those organizations.

RM: From my perspective, I often look nationally at different payers, providers, and others, and there are really four major transformations occurring: clinical transformations, redesign; organizational transformation occurring not only to accept risk but also to work in different ways than before; we’re seeing digital transformation, I think has been alluded to; and then financial transformation. So the big question is, what is the best structure to survive? Is there a difference? Next month we’ll look at the obligations and responsibilities you have with a democratic group in order to succeed, and what opportunities you get from that structure.

4 Responses to “Emergency Medicine Leaders Discuss Pros, Cons of Democratic Group Practices”

October 25, 2015

ED PhysicianTo Dr. Packards point.. I don’t think it is fair, logical, or even reasonable to conclude that what EMCARE is doing is “democratic”. I certainly think there are countless examples of completely unfair actions that EMCARE has taken against ED Physicians. I specifically have several, which I think if Dr. Packard new he would rectify. There in lies the problem.. EMCARE is so big that terrible atrocities are being done against ED Physicians and the people at the top don’t even know. In a democratic group, because it is smaller and the power is distributed these terrible actions are avoided. The profession of emergency medicine is being destroyed by this type of unaccountable behavior.

I hope Dr. Packard is interested in what is happening at a local level within EMCARE!!

October 25, 2015

John ShermanI think it unfortunate that the panel is mainly folk who are in the upper positions of apparently non-democratic groups. I get from the above discussions a paternalistic view: some people at the top know how to run the business better and that is the best way for it. It is then rationalized into the social darwinism framework of that is what is needed for groups/companies to survive. Rather Ayn Rand-ish. I also get the sense that a couple of the responses were being obviously obtuse with the sentiment that ‘some people want to do more of the administrative work and so it does not come out evenly’ – most ER doctors are smarter than that and know that administrative work is necessary and will proportion payment to those who are doing the “back office” work of the group. A good part of the chagrin from the “pit doctors” in a non-democratic group is over-valuing the administrative tasks compared to clinical work, to the point of the administrative level people in the organization getting considerable-fold higher incomes. That is the common “business-model” for corporations, but should it be that way for a group of professionals? I am a contractor for TeamHealth, and I would say that I have no particular say in anything the group does and know that a considerable portion of my revenue that I generate goes to a lot of administrative overhead that does not have transparent value.

I think the virtues of a democratic practice are good and could be strived for and incorporated into even “corporate model” groups of doctors.

October 26, 2015

Bill BassMany of us think that democracy is the fairest form of governance of any organization. Watch the video regarding democracy vs a republic ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JdS6fyUIklIto ) to really understand democracy.

The complexities of medical practice with it’s insurance, government, and regulatory burdens make solo practice almost impossible. A group that manages billing, insurance, malpractice insurance, pension plan, health insurance, CME, and scheduling well, certainly deserves a fair profit. That profit should be openly available to all group members a to see and invest in if they so chose. If you can find a group this open, you should join it.

Bill Bass, M.D.

November 5, 2015

Dominic Bagnoli, MD - CEO, USACSAs the co-founder and current CEO of one of the largest democratic EM groups in the country, I am acutely interested in this discussion and the comments that have followed. Being a democratic practice has been the gold standard in our specialty for decades and that hasn’t changed but as the discussion clearly highlights, there isn’t a consensus opinion as to what constitutes a democratic practice and for many, democracy is in the eye of the beholder. Realizing that there are many different perspectives of democracy, it occurs to me that we are using the wrong standard to judge an ideal EM practice. From my perspective, the real issue is equity and ownership. Do the practicing physicians own the practice? Do they have a path to ownership? What exactly do they own? I believe being an owner is the real difference maker. Everyone takes better care of something they own. Have you ever washed your rental car? Additionally, democratic and physician-owned groups will need more support and resources than ever to succeed in the progressively complex healthcare environment. All groups will need capital for investments in processes, infrastructure and technology in order to deliver better, more efficient care. Hospitals will also require support and partnership with world-class business leadership. It will be increasingly difficult, if not impossible, for smaller EM groups to access either of those. We are building a large EM group committed to physician equity and shared ownership for all of our members. Having a democratic vote is important, but it is not a substitute for being an actual owner of the practice.