“Foreign body–fishhook.” We commonly see these injuries in our emergency departments and think, “This could be a real pain to remove from wherever it may be.” Sometimes we need a simpler method, or even a MacGyver-like alternative to make our jobs easier, so our days spent in the trenches are more like our days wetting a line.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 06 – June 2016The Case

A 35-year-old, right-hand dominant, previously healthy male presents with a fishhook lodged in his right first digit. The injury occurred that morning, the opening day of trout season. His buddy tried meticulously to dislodge the hook to no avail. The patient now presents with finger pain and an inverted smile, and he is anxious to get back to that game of cat and mouse with an elusive nine-pounder that’ll win him a $250 gift card for the local tackle shop.

Background

Most fishhooks become embedded in either the hand or face. Unfortunately, some fishhooks will find their way into people’s eyes or even intracranially, as described in a case report in 1992.1,2 Obviously, ophthalmology will need to be consulted for ocular fishhook injuries, but the remaining majority of these occurrences can be dealt with in the emergency department.

Having the patient describe or even draw a picture of the fishhook will help the clinician decide which of the following techniques may be most appropriate for removal. The smaller size and shape of most recreational fishhooks keep them from penetrating deep into the soft tissue. However, commercial hooks and some sport-fishing tackle can be much larger and could very well access deeper neurovascular or bony structures. While not required for these accidents, radiographs can help identify the type of fishhook (eg, single-barbed, multi-barbed, treble), the size of the hook, its orientation within the soft tissue, and proximity to bony structures. Theoretically, using a water bath ultrasound technique, the emergency physician could identify nearby neurovascular structures that could be damaged when attempting to remove the hook. In that case, surgical colleagues should be consulted.3 Also consider consultation of a specialist when other vital regions (eg, joints, tendons, testicular, urethral, or peritoneal) are involved.

Classically, there are three different techniques that are used to remove embedded fishhooks: pull through, barb sheath, and string yank. There is a simple retrograde technique that is often attempted by the patient in the field prior to arrival. This technique is just as it sounds and is often only successful for very superficial hook injuries. As far as we know, there is only one prospective study that has reported success rates of these different fishhook removal techniques.1 In 1990, Doser et al evaluated 97 fishhook injuries that occurred in Alaska. They reported the greatest success rate (56/97, 58 percent) with the advance-and-cut technique when compared to all the other approaches. While the success rate was higher, they suggest attempting less traumatic retrograde techniques prior to progressing to advance and cut. Of the 87 injuries that were followed up, none had any complications or subsequent infections, despite the fact that only five patients were placed on prophylactic antibiotics.1

The discussion of who receives prophylactic antibiotics remains controversial and is left up to the provider. If antibiotics are deemed necessary, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or fluoroquinolones are preferred for gram-negative coverage of organisms that are commonly found in recreational water-sport injuries. As a general rule of thumb in fishhook accidents, if the hook is embedded superficially, then there is no evidence to support prophylactic antibiotics. However, if the fishhook is embedded deeper or near neurovascular structures, then providers should consider prophylactic antibiotics, depending on the type of exposure (eg, saltwater versus fresh water; see Table 1). Stronger consideration for prophylaxis should also be made if the patient is immunocompromised.4

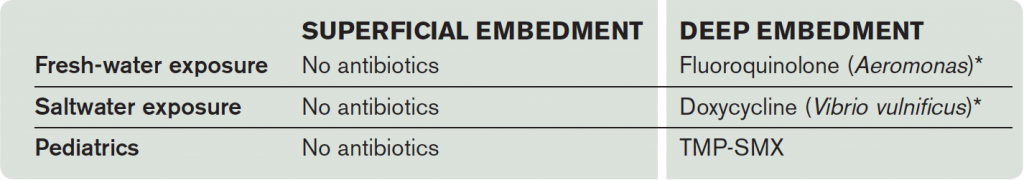

Table 1. Antibiotic Recommendations for Fishhook Injuries

*If the patient has an allergy to fluoroquinolone or doxycycline, use TMP-SMX as alternative coverage.

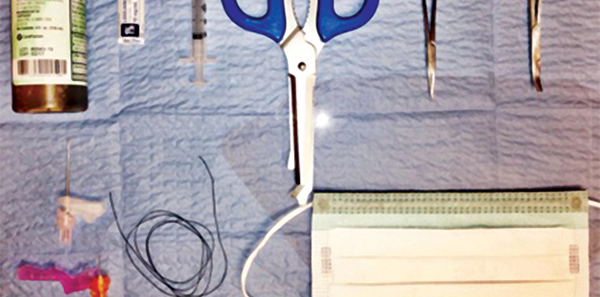

Equipment and Techniques (see Figure 1)4

- Povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine solution

- Local anesthetic solution without epinephrine

- 3 mL syringe

- Wire cutter

- Needle driver

- Hemostat

- 18-gauge needle

- 25-gauge needle

- String, fishing line, or 2-0 silk suture line, at least 50 cm in length

- Safety glasses, goggles, or a face mask with an eye shield for both the provider and patient

Proceed to cleanse the embedded area of debris, apply iodine or chlorhexidine solution, and allow the area to dry. Hooks with more than one point (eg, treble hooks) or lures/bait with more than one hook should have uninvolved points taped or cut off to prevent accidental embedding of uninvolved hooks while removing the embedded hook.5,6

Pull through technique for single- and multi-barbed hooks (see Figures 2 and 3).

This is a great technique for large-caliber hooks with barb near the surface of the skin in the ears, nasal cartilages, or joints. Once preparation of site is complete, proceed to locate the barb end of the hook and inject 0.5–1 mL of local anesthetic (without epinephrine) over the embedded barb region. Allow a couple of minutes for full anesthetic effect. Proceed by grasping the shaft end of the hook with needle driver and advancing the hook until the last barbed section of the hook is exposed. Grasp the barbed section with a hemostat. If a single-barbed hook (barbed only at the hook tip) is embedded, use wire cutters to cut the hook proximally (toward the shaft end), and with the needle driver, pull back on the shaft and withdraw reverse of the direction of entry. If a multi-barbed hook is embedded or barbs are located on the shaft, advance the hook until the hook and barb are exposed. Grab this end with a hemostat. Use a wire cutter to cut the shaft, and without losing control of hemostat, pull the hook through (advancing toward the direction of entry).4

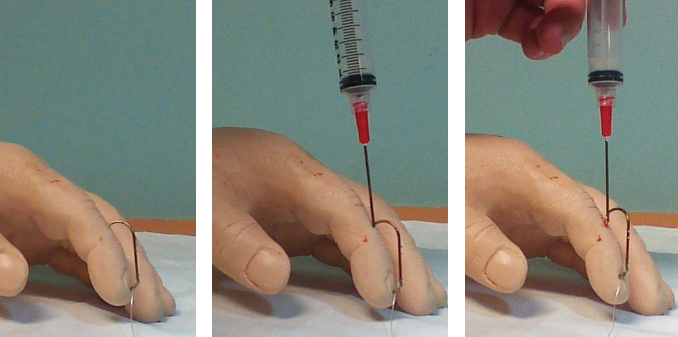

Barb sheath technique (see Figure 4). Normally, this is reserved for small hooks that are not embedded in the nose, in the ears, or near joints, as this is a more technically difficult technique that may cause further damage from blindly inserting an 18-gauge needle to disengage the barb. Firmly grasp the shaft end with the needle driver. Inject 0.5–1 mL of local anesthetic (without epinephrine) along the entry wound site of the fishhook. Insert an 18-gauge needle along the entry site, with the bevel facing toward the barb. Once the core of the needle has engaged the barb, slowly retract both the hook and the needle back out through the entry site.4

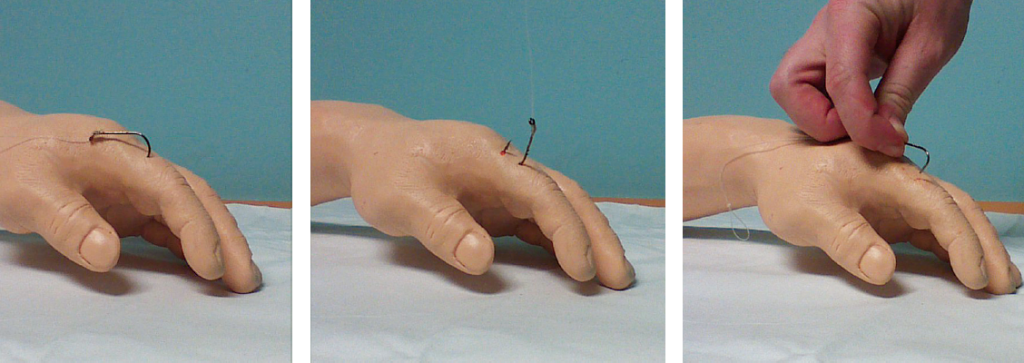

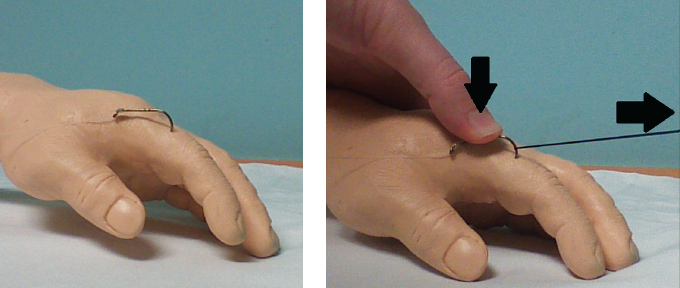

String yank technique (see Figure 5). This is likely the least painful technique for removing fishhooks. Although effective, this technique cannot be used on hooks embedded in ears, the nose, or joint cavities and is more suited for single hooks that are embedded into stable surfaces such as arms, the back, and the scalp region.6 Both the patient and the provider should wear eye protection. After cleaning up the area as previously described, loop a string around the bend of the hook. With your nondominant thumb or index finger, depress the shaft of the hook toward the embedded body part until it is parallel to the surface to disengage the hook. With a quick and firm jerk of the string, using your dominant hand, remove the hook. Local anesthetic is applied similarly to other techniques at the provider’s discretion. Many patients do not require an anesthetic, as experienced fishers often perform this procedure in the field.4

Case Conclusion

The fishhook is safely removed using the string yank technique. A dry dressing is applied, and the patient’s tetanus vaccine is updated. The fishhook was embedded superficially, therefore no prophylactic antibiotics are given. The patient will live to boast the big one next time.

Dr. Trinh works at Saint Barnabas Hospital in Livingston, New Jersey.

Dr. McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

Dr. McNamee is an attending physician at Emergency Medicine Professionals in Ormond Beach, Florida.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

References

- Doser C, Cooper WL, Edinger WM, et al. Fishhook injuries: a prospective evaluation. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9(5):413-415.

- Swanson JL, Augustine JA. Penetrating intracranial trauma from a fishhook. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(5)568-571.

- Blaivas M, Lyon M, Brannam L, et al. Water bath evaluation technique for emergency ultrasound of painful superficial structures. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(7): 589-593.

- Reichman E. Fishhook removal. Emergency Medicine Procedures. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education/Medical; 2013.

- McClary D. Saltwater fishing tips, tackle and techniques. Accessed May 12, 2016.

- Buttaravoli P, Leffler SM. Fishhook Removal. Minor Emergencies. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:543-546.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Emergency Medicine Techniques, Equipment List for Removing Fishhooks Lodged in Patients”