Although it is no longer unusual to see mass shootings in the news headlines, most people don’t expect one to happen in their hometown. As mass shootings become more common—and more deadly—though, emergency physicians increasingly may face the grim challenge of caring for multiple shooting victims while wondering how something like this could happen in their town.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 01 – January 2016

Mercy Medical Center, a hospital located in Roseburg, Oregon.

Ryan Petersen, MD, an emergency physician at Mercy Medical Center in Roseburg, Oregon, was enjoying an ordinary day of running errands when he got a call from his hospital that there had been a shooting at Roseburg’s Umpqua Community College,and that he was needed at Mercy to care for the victims. Ten people, including the gunman, died from the shooting, and nine others were injured. Ten of the victims were taken to Mercy Medical Center for treatment.

Dr. Petersen recently sat down with ACEP Now Medical Editor-in-Chief Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, to talk about his experiences caring for those injured in the shooting and how the event has affected both him and his community. Here are some excerpts from their conversation.

KK: Although it weighs heavy on people’s minds and hearts, I appreciate your being willing to talk about this. Where were you on the date of that event?

RP: I was actually driving to the store to pick up my 4-year-old’s birthday gift. I was about a half mile away from the hospital.

KK: What altered your course that day?

RP: I got a phone call from Melissa Norris, our on-site assistant, and she told me the initial report was there were up to 30 victims in a shooting at Umpqua Community College (UCC).

KK: Did you have your children in the car with you then?

RP: No, my wife was in Utah with both of my kids. I told Melissa, “I’ll be at the emergency room in a second,” hung up, called my wife, and I said, “There’s been a shooting at UCC. I want you to know that I’m OK, but I’m going to try to help out with it.”

KK: When you got there, how did the department look? Was it business as usual?

RP: The climate was definitely different. You could tell everybody was very tense. The entire emergency department was full of nurses, general surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, as well as the majority of the ER staff.

KK: What did you do with your existing patients?

RP: The existing patients basically were moved to the other side of the ER just to open up the main department so that we’d have the first 10 rooms open to take patients.

KK: Were people understanding when you told them that they were in the waiting room and that you wouldn’t be able to see them right away?

RP: That’s actually a very interesting story. The waiting room at that time was pretty full. The nursing supervisor went out and said, “I wanted to let you all know there’s been a shooting. There’s a number of very sick victims that are going to be coming in, and it’s probably going to be a one- to two-hour delay before we are able to bring anybody back.” All the people in the emergency department volunteered to leave and come back later.

KK: From the time you got to the department, how long before you started seeing some patients?

RP: Less than a minute. I got to the car, ran back, threw some scrubs on, and walked out. Lisa Beth Titus is our trauma coordinator. She was in the front doing triage, and she said, “You have 30 seconds or so. I’m going to send the first victims to the trauma rooms, and the third one I’ll send to you.” I popped into the room and introduced myself. I said, “We’ll be the team. We’ll assess this as fast as we can. If there’s something we can do for this patient, we’ll do it. And if we can’t, we’ll have to move on.”

KK: How many total patients did your department receive?

RP: We ended up getting 10. I think there were 20 total, with 10 deaths, and we ended up getting 10 of those in the ER.

KK: How many did you personally take care of?

RP: I took care of four.

KK: That’s plenty.

RP: The initial patient I got unfortunately sustained injuries that weren’t compatible with life, so we had to move on to the next one. The next three I got were all extremity injuries. The really ill patients had moved into the trauma bays and were being taken care of by Wade Fox, DO, FACEP, and Jennifer Bodenhamer, DO.

KK: If you care to share one moment from this whole event that weighed on you emotionally, I’d be interested to hear what that was.

RP: I think as ER docs, we’re pretty calloused. If you see terrible things on a daily basis, you’re really able to build up walls and deflect a lot of the stuff you see on a daily basis. You have someone who comes in, and they’ve been shot or stabbed. There’s always a degree of culpability with these patients, whether that’s imagined or true. You’ll find out that they’d probably not been doing the right thing at the right time, and so for me, that’s a coping mechanism. In this case, that just fell right on its face. These were just innocent kids who were assassinated, and that took a huge emotional toll on the physicians. It really hurt.

KK: In a 30-minute time frame that day, tell me about the gamut of injuries you saw, both for the patients who survived and those who did not.

RP: The first patient was a gunshot wound to the head. She was in asystole and was receiving CPR when she came through the door. You’re in triage mode at that point because you’re not sure what else is coming in. We took her pulse quickly, and she obviously had injuries that were not survivable. I moved from that team to the next room. That was a gunshot wound to the thigh; it was a superficial through and through. She was an 18-year-old whose mother actually was working in the hospital. The next two were both gunshot wounds to the hand, and I was able to pass those off to additional ER docs that came in.

KK: We all hear about these events, but we may feel insulated from them. That’s someone else’s community. How surprised were you that this was happening in your community?

RP: It’s really mind-blowing. I think President Obama talked about how we’ve become numb to this. You hear about all these tragedies around the country, and you really do become numb. You’re subjected to it constantly, but you always feel like that’s not going to happen here in this small, isolated, beautiful wilderness community. Everyone here was really shocked.

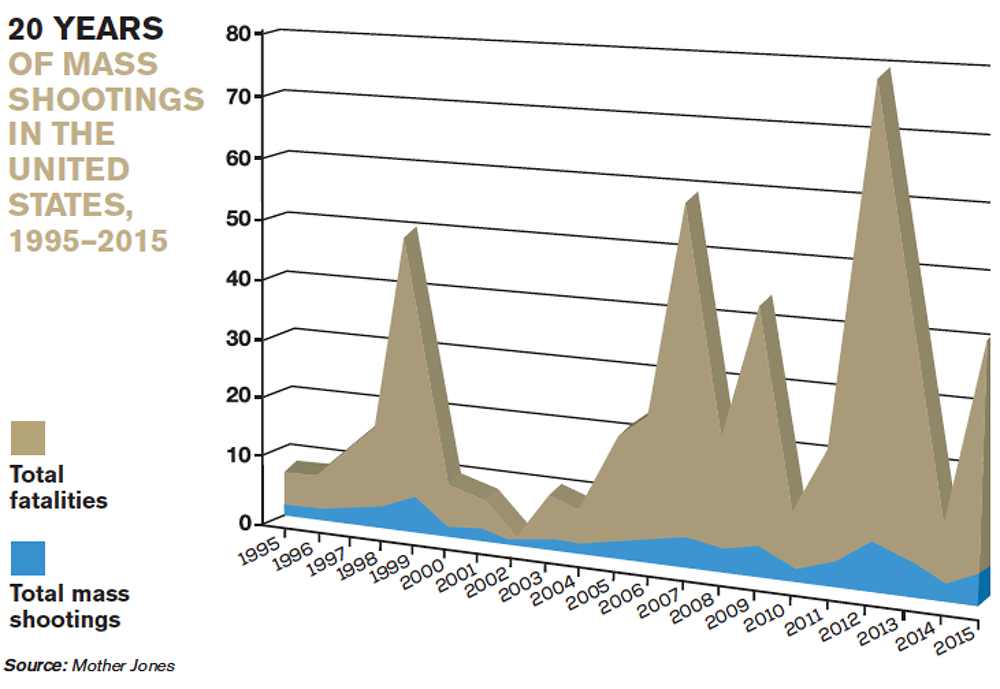

For this chart, a mass shooting is defined as an attack in a public place with four or more people killed. Mass murders in private homes related to domestic violence and shootings tied to gang or other criminal activity are excluded.

KK: When you have an event like this, we would like to believe this is just a day in the life of an emergency physician, but how has this changed you?

RP: I feel uneasy. I used to feel pretty isolated from this sort of stuff, and once it happens, you have a degree of uneasiness with the world. It’s hard to describe, but you worry about your kids and your family. I honestly don’t know if it will ever go away. Time heals all wounds, so I suspect with time you’ll lower this level of alertness, and things will come back to at least a degree of normalcy. This tragedy has had a profound effect on the doctors and nurses here, and I hope at some point in time that a degree of security comes back to me as well as the community.

KK: Despite the fact that it was difficult and challenging, it would have been worse not being able to participate and help.

RP: I felt fortunate that I was here and was able to help out with all the docs.

KK: Did you have any personal interaction with the families?

RP: Unfortunately, two of the kids who were killed I personally know. Anspach is one of the guys who works on the fire department that I’m the director for; his son Treven Anspach was killed. My family friends were involved as well. I’m not best friends with these guys, but we were closely associated with two of the kids who were killed.

KK: So it became even more personal for you. Do you think from an interpersonal perspective you were able to provide some guidance and some support for them?

RP: Honestly, I don’t know if I did. I think I was overtaken by all of this. I know that my wife was able to go to some of the families and provide dinners, but personally, I was overwhelmed with the aftermath and didn’t have a lot of time to go and spend with the victims’ families unfortunately.

KK: I don’t blame you. You shouldn’t be expected to. I’m glad your wife was able to support those that you knew.

RP: The community really rose up in terms of that. They set up a number of donations and sponsorships. I think the one gentleman who combatted the shooter had $700,000 within a couple of days in an account that they had set up. The community has had an amazing response.

KK: Thank you, Ryan, for sharing your thoughts. I know it’s got to be a sensitive topic.

RP: It’s kind of hard to talk about.

KK: Maybe your story can help prepare others down the road if they find themselves in a similar situation.

RP: Absolutely.

One Response to “Emergency Physician Recounts Caring for Oregon Mass Shooting Victims”

January 24, 2016

AliciaDr. Peterson,

Thank you for taking the time to share your experience. What a difficult experience, one I hope I never share with you. Emergency staffers are unique birds in their ability to cope. Your sharing shows that these types of circumstances take more than lives. I’d like to express gratitude to you and your ER staff for their work and service. While we (ER staff) all know that we could be faced with a disaster at any moment I take for granted that even my toughest shifts were mild in comparison to your experience. Peace to you and your staff!

ER Doctor in Flint, Michigan