Editor’s Note: The ACEP Council hosted a Town Hall meeting on mergers and acquisitions on Oct. 24, 2015, in Boston. Here is Part 3 of our edited transcript of the discussion. See the January and February issues for Parts 1 and 2, respectively.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 03 – March 2016Introduction

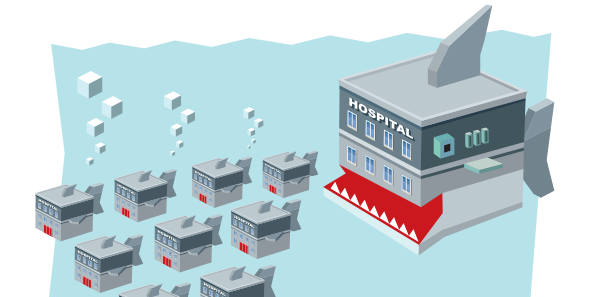

This is our Town Hall meeting and should represent a topic that is really important to the practice of emergency medicine, our specialty, and beyond: mergers and acquisitions. Many of us may not know a lot about this process and how it could impact us, but I think it’s time we discussed it so that we are all more informed about mergers and acquisitions in medicine. That’s why I titled this “Mergers and Acquisitions: The Medical Shark Tank.” I tried to get Mark Cuban; he still hasn’t responded to the request. I’ve asked Ricardo Martinez, who has a wealth of broad health care knowledge, to moderate this session.

—Kevin M. Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, ACEP Council Speaker (2013–2015), chief medical officer–emergency medicine and chief risk officer for TeamHealth, and ACEP Now medical editor-in-chief

Moderator

Ricardo Martinez, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer for North Highland Worldwide Consulting and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Emory University in Atlanta.

Participants

Brent Asplin, MD, MPH, FACEP, chief clinical officer for Mercy Health in Ohio

Savoy Brummer, MD, FACEP, vice president of practice development at CEP America in Belleville, Illinois, and chair of the ACEP Democratic Group Section

Ray Iannaccone, MD, FACEP, president of EmCare

Jay Kaplan, MD, FACEP, President of ACEP; director of the patient experience for CEP America in Emeryville, California; and a practicing clinician in the emergency department at Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae, California

JK: Culture doesn’t stand by itself. If it’s a synergistic relationship and the quality of the organizations both improve, then that’s a match made in heaven, and it becomes a win-win. On the other hand, if two organizations come together and the quality, outcomes, and revenue don’t meet expectations and in fact suffer a little bit, that’s when things fall apart.

SB: As important as culture is, it’s less important to people outside of our market. How many random telephone calls does the C-suite of CEP get every month from private-equity or hedge funds, saying, “We’d like to purchase your organization for X multiple”? Again, as much as we talk about culture, there are those outside of our industry who really look at the numbers.

BA: I’ll give you some great questions from Pat Lencioni, which are great questions to answer whether you’re considering a merger or not. They are really helpful and powerful: Why do we exist? (What is your mission?) How do we behave? (What are your values?) What do we do? (What are we really trying to accomplish together?) How do we think we’ll be successful together? If you are considering a merger with another entity and you don’t have alignment at all in the first four, it might not be the best idea.

Brent, as a hospital administrator, are you and the American Hospital Association willing to sit with me as President of the College and have a discussion about why hospitals are shifting huge overhead to the emergency departments? Since over 75 percent of emergency hospital bills are related to hospital charges, could we have a conversation about making the visit cheaper for the patient? —Jay Kaplan, MD, FACEP

RM: Here’s my last series of questions: How does emergency medicine best grow? Where are we going to be? Where do you see us being as a specialty in five years? What kind of structure do you see us operating in?

BA: There’s a huge opportunity in alternative payment models to help at the interface of inpatient and outpatient care. Emergency medicine will always be at that interface. I think the groups that are helping systems get at value and lower their costs (avoid potentially avoidable admissions, creating alternatives to admission, providing care-transition support) are going to be a growth opportunity. The ability to do free pricing for freestanding centers is going to be eroded pretty quickly. Run your pro forma both ways under freestanding and hospital-based pricing because it could get pretty ugly on the hospital-based pricing front. Not all systems are interested, but the ones that are in virtual care are going to be in good shape.

SB: I’m going to quote Wes Curry. He tells me all the time, “I think we’re at a tipping point.” Those groups that will continue to demonstrate performance will succeed. Those who have tried to become the lowest-cost bidder yet deliver a very weak product will fail.

RI: There’s a lot of business wisdom that says stick to your core, but there’s a lot of exciting stuff going on with virtual medicine, navigation, population health management, and care management. I’d rather be the one providing those services, or at least providing the navigation through those services, rather than someone else. I do not want to be walking around five years from now with the same three tools in my toolbox: doctor, physician assistant, and scribe. I’d like to have 10 different tools.

The ability to do free pricing for freestanding centers is going to be eroded pretty quickly. Run your pro forma both ways under freestanding and hospital-based pricing because it could get pretty ugly on the hospital-based pricing front. —Brent Asplin, MD, MPH

JK: I have quoted Tom Peters for years: “If the other guy’s getting better, you better be getting better faster. If that other guy’s getting better, you’re getting worse.” This means, paradoxically, you can be getting better and getting worse at the same time if the other guy is getting better faster than you are. The only thing you ever have is a leading edge. We have to rebrand emergency medicine. Myles Riner did a study a number of years ago where he looked at over 6,000 claims. He found that if you took the 20 percent least-acute patients out of the system, you’d save only 4 percent of the cost. If you decrease computed tomography scans by one out of 12, you would save that much money as well. We have to do away with the myth that the emergency department is the most expensive place to receive care. ACEP has an alternative payment model task force. We have one looking at Medicaid access. We also have one looking at out of network and balance billing.

BA: It’s true that emergency medicine is not going to go away, and it’s critical and adds tons of value to the system, but if I can get 4 percent on a $730 million book of business, I’ll take the $29 million. I’m going to get the ED visits out that I can because not all of them do add value. I don’t think it’s a myth that the ED is a high-cost place. If it’s an ankle sprain, do you want to write a $1,200 check, or do you want to write a $200 check?

JK: Brent, as a hospital administrator, are you and the American Hospital Association willing to sit with me as President of the College and have a discussion about why hospitals are shifting huge overhead to the emergency departments? Since over 75 percent of emergency hospital bills are related to hospital charges, could we have a conversation about making the visit cheaper for the patient?

BA: It’s going to happen. It’s hospital-based pricing, and I say to my colleagues all of the time, it’s going to get cut. The hospital can’t escape it, so if they can’t reduce their costs, they’re not going to be successful. I wanted to throw that in there because it was feeling more like a waiting room bubbler tank than a shark tank.

RM: It is a shark tank, so shark away. Prices are dropping now that it’s becoming more visible to people. The average deductible is $1,500 for hospital admission. The average person has less than $1,000 in savings, so do the math. That’s called bad debt, and it’s a lot.

Audience: For a lot of us, getting merged or acquired is a contract of adhesion. We don’t have a lot to say about it. What are the warning signs? When do you stay, and when do you start pulling up stakes and looking for someplace else?

RI: Four years ago, Emergency Medical Associates (EMA) looked at, “Should we do something?” We decided, no, we shouldn’t. We ended up having these big meetings with 200 partners. This time when we did it, the board came to me and said, “We’re just going to do this as a board because it was very disruptive doing it the other way.” The board did a lot of deliberation, and the partners of EMA voted yes or no. Was it a secret that we were having these discussions? No. What were the warning signs? There were lots of meetings that don’t normally take place and parking lots filled with cars that you don’t recognize. If you’re an owner, hopefully you have a voice. If you’re in a group where you’re not an owner but they have a culture of including physicians and they invite your opinions, then you should give them and ask for information. The other thing you should do is check your employment agreement. There may be protections or considerations included.

JK: You should look around and start seeing if there is an option for you that will allow you to get something from your years of service. There are some groups where they will give you a certain amount of partnership for years that you’ve been practicing with them. There are some options where you may be able to retain local control and still be part of a larger group.

If you’ve got a lot of partners that are toward the end of their career and they have an idea that their lifelong investment now needs to be monetized, I think that’s a very clear warning sign. —Savoy Brummer, MD, FACEP

SB: I think one problem with many groups is that they originated and began without the end in sight. Many times, independent practices will see there’s an issue but will be too paralyzed because of their structure to actually do something about it. If you’ve got a lot of partners that are toward the end of their career and they have an idea that their lifelong investment now needs to be monetized, I think that’s a very clear warning sign. When groups are using creative financing to deal with some of their financial obligations, clearly that’s a problem. If there are any preferred partner arrangements or joint-venture agreements, I would immediately consider that a threat as well.

Audience: When does an acquisition become predatory? I have a very close friend. His CEO tapped him on the shoulder and said, “You know, we want you to joint venture with this particular organization. It’s going to be such a great deal for you. You’re going to give them all your revenue; they’re going to split the profit with us, the hospital, and we’re going to pay you less because you’re paid too much. We want to keep you because we love you, but you know that Tesla that’s in the parking lot is too much.”

BA: You just answered your own question. I think that’s a description of when it’s predatory, and ACEP should take a stand on that. I don’t know whether or not you’ll be able to stop it, but I think that’s a pretty clear example of when it gets predatory.

JK: If hospitals are coming and saying to physician groups, “You have to joint venture with us, and in return, we’re going to take some of your professional fee and feed it back to the hospital,” then that’s fraud, and ACEP should take a strong stance with regard to that.

Audience: I learned in business school there’s no such thing as a merger. They are always acquisitions. My question is, what are you seeing, and are there any activities about expansions beyond the usual SNF-ist [skilled nursing facility], hospitalist, acute care model to partnering?

JK: We have a task force on alternative payment models. With the whole concept of bundled payments, we think they are going to carve out emergency medicine, and I think the carve out is going away sooner than we expected. [Editor’s Note: See page 16 for a 2016 update on bundled payments.]

If you’re an owner, hopefully you have a voice. If you’re in a group where you’re not an owner but they have a culture of including physicians and they invite your opinions, then you should give them and ask for information. The other thing you should do is check your employment agreement. There may be protections or considerations included. —Ray Iannaccone, MD, FACEP

RI: Over the last five to seven years, we’ve gone from a situation where hospital administrators would never consider putting more than one service line under one contract to the exact opposite.

SB: We’re seeing that universally across the market. Hospital CEOs will say, “You’ve done such a great job in the ED. Will you take a look at the hospitalists? Can you take a look at cardiologists?”

RM: I’m going to tell you from my days in capitated care that when the pie gets smaller, the table manners change.

Audience: A large part of our income comes from private insurance companies, and there are high-profile planned mergers of four of the five largest insurers in the United States. What is the marginal value of private for-profit health insurance vis-à-vis a public payer like Medicare?

JK: The term health insurance company is an oxymoron because health insurance companies do not exist for the health of their patients and their clients. They exist to make profits for their shareholders. We need to go after the insurance companies and have them show their true colors as best we can, and we need to ally with our patients.

Audience: I’m representing the Section on Medical Humanities. This was not a very humanistic discussion, not much poetry, but my question is actually concerning what happens to academic medical centers [AMCs] in all of these changes. AMCs are more expensive than typical community hospitals. My question is, what’s the role of emergency medicine in helping academic medical centers to successfully navigate some of the changes that are coming down the road?

BA: There will be fewer AMCs, and that’s a larger dilemma for the educational needs of the country than it is for the clinical needs of the country. Community systems that can partner with AMCs on an educational mission are going to be needed. I don’t know that all of the AMCs we have currently are going to be needed for the quaternary needs of the population. In emergency medicine, we’re systems experts. To the degree that we can help strengthen those community and academic partnerships in our markets, that’s the area that’s going to help academic medicine the most.

RM: Academic hospitals lose money on teaching, they lose money on research, and they have very high fixed costs. They have a problem.

Audience: The evidence that I’ve seen out there suggests that consolidation raises prices. It may decrease costs, but those costs are often pocketed by the institutions they’re consolidating, and there’s very little evidence the consolidated institutions actually have increased quality. I’m wondering what the case is for the nation and for our patients to encourage consolidation under those circumstances.

BA: These are market forces, and you’re not going to be able to stop the market forces from doing it. Your points are well taken. The successful consolidations will be those that are able to lower total cost of care for populations and be able to tell a quality and value story associated with it. Having the infrastructure to do this new work is so expensive. We’ll spend $30 million next year on care management, IT, analytics, new resources, clinical pharmacists, call centers, and data aggregation tools to try to be successful in a population health framework. You can’t duplicate that without having scale.

No Responses to “Emergency Physicians Discuss Mergers, Money, Future of Emergency Medicine at ACEP15 Council Town Hall”