A 28-year-old female is brought to the emergency department (ED) by police after a sexual assault. She is visibly anxious and tearful. The police officer is waiting for the sexual assault evidence kit. What is the trauma-informed approach to care for this patient?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 12 – December 2024Introduction

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines trauma as “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”1 A significant number of patients present to the ED with concerns related to traumatic experiences. These concerns may be a direct result of trauma (e.g., injuries following an assault), or an indirect result of trauma (e.g., substance abuse as a coping mechanism following traumatic events).

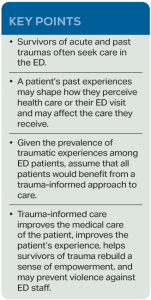

Patients’ subsequent experiences in the ED may be re-traumatizing or trigger memories from past experiences.2 The chaos of the ED, lack of privacy, fear, pain, physical touch, and invasive history questions may provoke a trauma response. Patients may be anxious, hypervigilant, and even combative. Conversely, they may respond to real or perceived threats by “shutting down” and not participating in their care, even refusing certain aspects of care or procedures. Trauma responses in the ED present a challenge to ED staff and may prevent the optimal provision of care. Given the prevalence of trauma among ED patients, clinicians should assume that all patients would benefit from a trauma-informed approach to care.

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is an approach to the delivery of care that includes an understanding of trauma and an awareness of the effect it may have on the individual or patient. Use of the principles of TIC improves the medical care of the patient, improves patient experience, helps survivors of trauma rebuild a sense of empowerment, and may prevent violence against ED staff.

According to SAMHSA, for an organization to provide TIC, it must abide by four principles:1

- Realization of the widespread effect of trauma and understanding of potential paths for recovery;

- Recognition of the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, staff, and others involved in the system;

- Response by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and,

- Active resistance against re-traumatization.

TIC is based on six principles: 1) safety; 2) trustworthiness and transparency; 3) peer support; 4) collaboration and mutuality; 5) empowerment, voice, and choice; and 6) cultural, historical, and gender issues.1 There are a multitude of ways to incorporate TIC throughout the ED encounter.3,4

History

During the initial evaluation of the patient, the physician should establish the ED as a safe space for the patient. Simple actions such as knocking and asking permission to enter the room may provide reassurance to the patient that their preferences will be taken into consideration. Clinicians should confirm the pronunciation of the patient’s name, use their preferred pronouns, and use an interpreter, if necessary. Ask whether the patient wants others (friends or family members) in the room during the history and examination. The patient may not feel empowered to ask visitors to leave, so this should be addressed by the clinician. Conversely, the patient may feel safer with friends or family members present in the room or on speaker phone.

Physical Examination

Clinicians should describe the steps of the physical examination so that the patient knows what to expect and should ask for consent to do the examination, especially of sensitive areas of the body. Stress to the patient that they can refuse any or all parts of the medical forensic examination. The patient should be offered as much privacy as possible during the examination. This may mean moving a patient from a hallway bed into an examination room or using adequate draping techniques. The clinician should also ask questions such as, “Is there a part of the examination that is worrisome to you? Is there anything we can do to make you more comfortable?”

Procedures

Procedures, including necessary equipment, should be explained in as much detail as the patient would like. After obtaining consent, the clinician should provide as much pain relief as possible prior to the procedure. Ask the patient about preferences regarding position of comfort and whether they want a support person present. Give the patient as much control as possible. The speculum or pelvic exam can be triggering to a patient with a past history of sexual abuse or assault; therefore, patients may prefer to self-insert a speculum or to self-swab the genitals. If the patient needs a break during the procedure, this should be provided if possible.

Disposition

Shared decision making is key to empowering patients in their own medical care. If the patient is being discharged, ensure appropriate referral and community resources. Because many ED patients are experiencing stress, which may interfere with comprehension and retention of instructions, methods such as teach-back should be used. Patients should be asked what questions they have, and resources should be provided in case they have questions following disposition.

Case Conclusion

You sit down at the patient’s level, confirm name and preferred pronouns, and introduce yourself. You ask if she would like to have a friend, family member, or the rape crisis advocate present during the ED encounter. After obtaining a history, you describe the physical examination and evidence collection. The patient is anxious about the speculum examination and genital swabs, so you show her the equipment and answer her questions. After obtaining consent for the examination, you do the exam and evidence collection, talking through each step, and providing draping for the patient’s privacy. You confirm that she does wish to have evidence turned over to the police. You engage the patient in decisions regarding post-exposure prophylaxis and post-coital contraception. All her questions are answered, and she is discharged with outpatient resources, including contact information for the rape crisis center.

Dr. Rozzi is an emergency physician, director of the Forensic Examiner Team at WellSpan York Hospital in York, Pa., and chair of the Forensic Section of ACEP.

Dr. Rozzi is an emergency physician, director of the Forensic Examiner Team at WellSpan York Hospital in York, Pa., and chair of the Forensic Section of ACEP.

Dr. Riviello is chair and professor of emergency medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Dr. Riviello is chair and professor of emergency medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

References

- SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-informed Approach. Published July 2014. Accessed November 3, 2024.

- Purkey E, Davison C, MacKenzie M, et al. Experience of emergency department use among persons with a history of adverse childhood experiences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):455.

- Ashworth H, Lewis-O‘Connor A, Grossman S, et al. Trauma-informed care (TIC) best practices for improving patient care in the emergency department. Int J Emerg Med. 2023;16(1):38.

- Greenwald A, Kelly A, Thomas L. Trauma-informed care in the emergency department: concepts and recommendations for integrating practices into emergency medicine [published correction appears in Med Educ Online. 2023 Dec;28(1):2206681]. Med Educ Online. 2023;28(1):2178366.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Employ a Trauma-Informed Approach to Care”