A disability is any condition of the body or mind that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities and interact with the world around them.1 This includes impairments or difficulty with: vision; movement, processing, or thinking and remembering; verbal or non-verbal communication; mental health; hearing; or relationships. People often compartmentalize others based on their abilities and disabilities, but these patients are the opposite; instead, their range of ability should be viewed on a spectrum.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 11 – November 2023The care of patients with disabilities in the ED requires more attention, as not much data is available. Krahn, et al., highlight some discrepancies in experiences that may result in ED visits.2 For example, patients that live with disabilities are twice as likely to report sexual assault compared to those without a disability.2 They are one and a half times more likely to be a victim of a nonviolent crime.2 Having a disability alone puts you at a higher risk for unintentional injuries, more than the impact of your age, gender identity, racial background, or education level.2 There have been calls to implement educational resources for emergency medicine residents, but there have not been any tools to better manage these patients.3 The need for this type of investigation was further highlighted in an article by York, et al.—an extensive review of the care these patients receive and how it can be improved.4

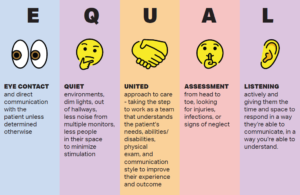

This new approach to caring for folks with disabilities uses the concept of EQUALity, which stands for Eye contact, Quiet environment, United approach, Assessment from head to toe, and Listening actively (See Figure 1). The hope is that this model will be an easy reference tool for providers best to monitor their bias when caring for these patients, a discussion started by Dr. Poffenberger regarding using appropriate language.5 This new mnemonic aims to expand further not only on using inclusive language, but also on improving our physical exam, environment, and comprehensive care. The barriers that these patients experience can result in delayed or missed diagnoses if the providers are not thorough in examinations, history taking, and obtaining collateral information. One case report highlighted an unfortunate outcome from aspiration pneumonia, later found to be due to crayons rather than the expected culprits such as food, secretions, or beverages.6 Some cases may be unavoidable, but it is very important to consider alternative diagnoses.

Eye contact is important as a part of nonverbal communication and body language to demonstrate understanding, respect, and attention. Upon entering a room, make eye contact with your patient and address them directly as you would any other patient. It is important not to assume their communication abilities based on their diagnosis. Introduce yourself, explain your goals, and evaluate their response. If there is a caretaker available, you can ask the patient for permission to have the caretaker contribute to the history. You can also always ask, with the caretaker or family member at bedside, “How do you communicate?” They can tell you if the patient uses words, hand squeezes, gaze changes, blinking, sounds, or changes in expression. You also can ask about how the patient expresses pain, as this will be helpful in how you evaluate for tenderness.

Quiet environments can be crucial for patients with sensory or processing difficulties, namely those living with autism spectrum disorder. For these patients, the ED can be a very overstimulating place to be, especially when they are already experiencing new feelings due to getting sick. Evaluating them in a less stimulating space can be helpful in getting the best possible exam, improving outcomes, and reducing the need for de-escalation and sometimes, chemical sedation. The ED is constantly overloaded with patients, so this will require some teamwork to coordinate, including nursing staff, pod lead, and other clinicians.

United approaches to care for these patients are also needed, in that communicating with all staff interacting with this patient can improve their experience. The care team should be aware of how this patient communicates and expresses pain, what their needs are, what their abilities are, and their physical exam findings. This preserves patients’ dignity because everyone acknowledges the abilities of this patient and how they are being addressed. It also helps with prevention. Communication between providers and nursing regarding indwelling devices, bed sores, cleanliness, or signs of neglect is important, as the thoroughness of each examination may vary. This makes documentation and communication of the utmost importance for these patients for their health and safety.

This leads into the next part of the model—Assessment. This is important in most of our patients with disabilities, but especially those who cannot communicate their complaints verbally or with a device. Instead, we resort to vital-sign abnormalities, physical exam findings, or suspicion from their care partners. Their care partners typically know when something is abnormal, and more often than not their concerns are correct. In the scenarios where we are unable to find a care partner or family member, a head-to-toe physical assessment is important, starting with vitals. While vitals may be abnormal for some, they may be normal for that patient. The inverse is also true; what’s normal for most may be significantly abnormal for that patient and be the first red flag. One commonly used example is tachycardia. Oftentimes, it can be an indication of pain, infection, distress, anxiety, dehydration, or the first sign of sepsis. Remove all braces, prosthetics, and clothing, check the undersurfaces and intertriginous areas, look for bruising or fractures, evaluate all indwelling devices (tracheostomy sites, gastrostomy-jejunostomy tubes, foleys, peripherally-inserted central catheter lines and ports), and inspect nail beds, ears, and teeth. These are all important places to examine, as they can hide infections, or be signs of possible neglect. As mandated reporters, especially for vulnerable populations, this type of exam is necessary.

Listening actively is the final portion—and arguably one of the most meaningful portions of patient care. When a patient can communicate with you in a way that you can understand, give them the time and space to communicate. Be patient and give them your attention. If they are part of the Deaf community, ensure that they have an American Sign Language interpreter present, as well as an in-person interpreter to best communicate the emotion behind their speech. Body language is especially important here and reinforces why maintaining good eye contact, using appropriate language that includes the patient in the dialogue, and asking permission to speak with family or care partners are pivotal factors in their care.

Using the EQUAL model will hopefully improve our care of patients living with disabilities, as well as their experience in the ED and accessing healthcare. Historically, they have multiple comorbidities, making them sicker at baseline. One study highlighted that those with a disability have higher adverse outcomes and incidence of cardiovascular disease and diabetes across the board, and that disabled women receive less health maintenance screening.2 This means that their presentation is likely higher-risk and requires more diligent examination. With this model, there will hopefully be improved patient satisfaction and better outcomes.

Dr. Earle is a third-year emergency medicine resident at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

Dr. Earle is a third-year emergency medicine resident at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

References

- Disability and health overview. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html. Published September 16, 2020. Accessed October 10, 2023.

- Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 2):S198–S206.

- Rotoli J, Backster A, Sapp RW, et al. Emergency medicine resident education on caring for patients with disabilities: A call to action. AEM Education Train. 2020;4(4):450–462.

- York J, Wechuli Y, Karbach U. Emergency medical care of people with intellectual disabilities: A scoping review. Open Access Emerg Med. 2022; 14: 441–456.

- Poffenberger C, Backster A, Rotoli J. Emergency physicians’ perspective: caring for persons with disabilities. EM Resident. 2023;50(1):58–59.

- Yocum AD, Simon EL, Dennison JL. Esophageal obstruction and death in a nonverbal patient. J Emerg Med. 2021;60(5):e109-e113.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “EQUAL: a Straightforward Approach To Caring for Disabled Patients”