During your busy shift, you get a call that a 27-year-old G3 P2 female who is 28 weeks pregnant has been involved in a motor vehicle collision. She was the restrained driver in a front-end 25-mile-per-hour collision with airbag deployment. The obstetrician-gynecologist team has tasked you with “clearing” the patient from a trauma perspective before she comes to the labor and delivery floor for monitoring. She complains of some abdominal discomfort. On exam, she has no seatbelt sign. You reach for your trusty ultrasound machine to perform a focused sonography for trauma (FAST) exam and obtain all the necessary views. Then you ask yourself, is the FAST exam even applicable in pregnancy?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 01 – January 2020Background

Trauma is a leading cause of nonobstetric maternal mortality and affects up to 7 percent of all pregnancies. Both major and minor trauma increase the risk of a pregnancy loss, but pregnant trauma patients are more likely to sustain serious abdominal injuries than nonpregnant trauma patients. The overall fetal loss rate from trauma is reported to be anywhere from 1 percent to 34 percent.1 The fetal loss rate with penetrating abdominal injuries is far higher, at 73 percent.2,3 Additionally, life-threatening traumatic injuries to a pregnant patient should always be considered a life-threatening condition for the fetus because maternal death almost always results in fetal death.4

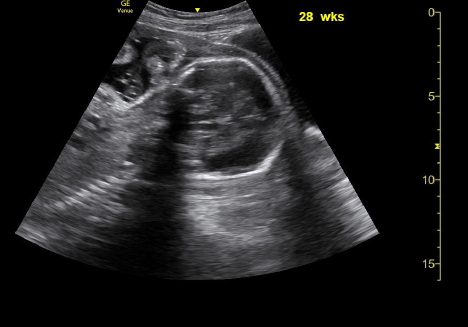

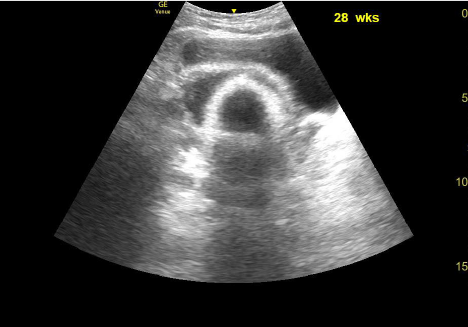

Sagittal and transverse

Because of the risks to both the mother and fetus, emergency and trauma physicians will want to be confident in their physical assessments of pregnant patients with traumatic injuries. Generally, ultrasonography is a preferred imaging modality for this patient population due to lack of radiation exposure. However, the FAST exam, one of the most commonly used assessments to look for free intraperitoneal and pericardial fluid from internal trauma, may be unreliable in pregnant patients.

Limitations of the FAST Exam

The most obvious aspect of the FAST exam that may be different than usual is the pelvic portion of the exam, which can be challenging due to the anatomical changes that accompany pregnancy. Of particular concern is the evaluation of the pouch of Douglas for the presence of hemoperitoneum, which requires special and more advanced ultrasound training than for nonpregnant patients.5

Pelvic ultrasound of a female who is 28 weeks pregnant.

The most common cause of pregnancy loss with nonfatal maternal traumatic injury is placental abruption. This is sometimes assessed during the FAST exam, often when attempting to establish ongoing fetal heart motion, fetal activity, amniotic fluid volume, and gestational age.1,5-7 However, ultrasound is insensitive in diagnosing placental abruption, and a true diagnosis often requires continuous cardiotocographic monitoring.8,9 Furthermore, as in nonpregnant trauma patients, the FAST exam may fail to identify small amounts of intraperitoneal fluid and specific organ injury in pregnant patients.10-14

Sensitivity and Specificity of the FAST Exam

Previous studies on the use of the FAST exam in nonpregnant adult blunt trauma patients have found the FAST exam’s detection rate to vary from 79 percent to 98 percent.15-18 Several studies have attempted to establish the utility of FAST exams as similar in pregnant and nonpregnant women, but the relatively small sample sizes for calculating sensitivity render the findings difficult to rely upon.

When Goodwin and colleagues looked at the use of abdominal ultrasonography to examine pregnant blunt trauma patients, they found a sensitivity of 83 percent (95 percent confidence interval [CI], 36–100 percent) and a specificity of 98 percent (95 percent CI, 93–100 percent). Their sensitivity value determination was based on an evaluation of only six sonographers—although the total sample size was 127 patients.19

Brown and colleagues found the sensitivity of screening sonography for use in pregnant patients with blunt abdominal trauma to be 80 percent (95 percent CI, 28–100 percent), but only used five patients to determine this value.20 Although their reported specificity was 100 percent (95 percent CI, 96–100 percent) for 96 patients without abdominal injury, Brown et al concluded that they “cannot make strong conclusions about sensitivity on the basis of this small study.”20

In a 10-year retrospective study of ultrasound evaluations in pregnant abdominal trauma patients, Meisinger and colleagues determined the sensitivity and specificity of their institution’s extended FAST exam to be 85.7 percent and 99.7 percent, respectively. However, their sensitivity value was calculated based on the findings of only seven patients, and the researchers attributed their higher sensitivity value to the greater training of their sonographers.21

A study by Richards and colleagues had the largest number of positive cases (n=23) from which a calculation for sensitivity of the FAST exam could be estimated. They found the sensitivity to be 61 percent, the lowest of all the studies. This low sensitivity compelled them to conclude that the FAST exam “does not rule out intra-abdominal pathology.”22 Their specificity was 94.4 percent for 288 out of 305 patients.22 Taken together, the sensitivity values in the existing literature, which were calculated based on small sample sizes and have large margins of error, are uncertain indicators of the FAST examination’s reliability in detecting signs of blunt trauma within pregnant patients. However, the high specificity in these studies suggests that the presence of positive findings may be enough information to act upon.

Conclusion

The utility of the FAST exam in pregnant trauma patients has yet to be fully validated by existing research and may prove a challenge for providers who are less experienced in ultrasonography. As is the case with many applications of bedside ultrasound, positive findings appear to be quite reliable (ie, high specificities). However, false negatives remain a concern. More research is required to determine the true sensitivity of the FAST exam in this patient subset and to address potential challenges. Researchers continue to emphasize that ultrasound should not be used in place of a diagnostic computed tomographic examination in the treatment of pregnant patients with a high suspicion of internal injury.5,23-25 Patients (without any further imaging) with concern for occult injury should be admitted to labor and delivery and monitored for 24 hours without adverse events before discharge.

Dr. Wilson is emergency ultrasound director, ultrasound fellowship director, and clinical assistant professor at the University of South Carolina in Columbia and the Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine in Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Ms. Dickson is a medical student at the University of South Carolina.

References

- Shah KH, Simons RK, Holbrook T, et al. Trauma in pregnancy: maternal and fetal outcomes. J Trauma. 1998;45:83-86.

- Sandy EA 2nd, Koerner M. Self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the pregnant abdomen: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Perinatol. 1989;6:30-31.

- Petrone P, Talving P, Browder T, et al. Abdominal injuries in pregnancy: a 155-month study at two level 1 trauma centers. Injury. 2011;42:47-49.

- Lowdermilk C, Gavant ML, Qaisi W, et al. Screening helical CT for evaluation of blunt traumatic injury in the pregnant patient. Radiographics. 1999;19(spec no):S243-S255.

- Richards JR, McGahan JP. Focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) in 2017: What radiologists can learn. Radiology. 2017;283(1):30-48.

- Rogers FB, Rozycki GS, Osler TM, et al. A multi-institutional study of factors associated with fetal death in injured pregnant patients. Arch Surg. 1999;134(11):1274-1277.

- Weiss HB, Songer TJ, Fabio A. Fetal deaths related to maternal injury. JAMA. 2001;286:1863-1868.

- Sadro C, Bernstein MP, Kanal KM. Imaging of trauma: part 2, abdominal trauma and pregnancy—a radiologist’s guide to doing what is best for the mother and baby. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(6):1207-1219.

- Richards JR, Ormsby EL, Romo MV, et al. Blunt abdominal injury in the pregnant patient: detection with US. Radiology. 2004;233(2):463-470.

- Grüessner R, Mentges B, Düber C, et al. Sonography versus peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1989;29:242-244.

- Rozycki GS, Ballard RB, Feliciano DV, et al. Surgeon-performed ultrasound for the assessment of truncal injuries: lessons learned from 1540 patients. Ann Surg. 1998;228:557-567.

- Rose JS. Ultrasound in abdominal trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22(3):581-599.

- Shackford SR, Rogers FB, Osler TM, et al. Focused abdominal sonogram for trauma: the learning curve of nonradiologist clinicians in detecting hemoperitoneum. J Trauma. 1999;46(4):553-562.

- Branney SW, Wolfe RE, Moore EE, et al. Quantitative sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting free intraperitoneal fluid. J Trauma. 1995;39(2):375-380.

- Hoffman R, Pohlemann T, Wippermann B, et al. Management of blunt abdominal trauma using sonography. Unfallchirung. 1989;92:471-476.

- Goletti O, Ghiselli G, Lippolis PV, et al. The role of ultrasonography in blunt abdominal trauma: results in 250 consecutive cases. J Trauma. 1994;36:178-181.

- Röthlin MA, Näf R, Amgwerd M, et al. Ultrasound in blunt abdominal and thoracic trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34:488-495.

- Kimura A, Otsuka T. Emergency center ultrasonography in the evaluation of hemoperitoneum: a prospective study. J Trauma. 1991;31:20-23.

- Goodwin H, Holmes JF, Wisner DH. Abdominal ultrasound examination in pregnant blunt trauma patients. J Trauma. 2001;50(4):689-693.

- Brown MA, Sirlin CB, Farahmand N, et al. Screening sonography in pregnant patients with blunt abdominal trauma. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24(2):175-181.

- Meisinger QC, Brown MA, Dehqanzada ZA, et al. A 10-year retrospective evaluation of ultrasound in pregnant abdominal trauma patients. Emerg Radiol. 2016;23(2):105-109.

- Richards JR, Ormsby EL, Romo MV, et al. Blunt abdominal injury in the pregnant patient: detection with US. Radiology. 2004;233(2):463-470.

- Richards JR, McGahan JP, Pali MJ, et al. Sonographic detection of blunt hepatic trauma: hemoperitoneum and parenchymal patterns of injury. J Trauma. 1999;47(6):1092-1097.

- Brown MA, Casola G, Sirlin CB, et al. Importance of evaluating organ parenchyma during screening abdominal ultrasonography after blunt trauma. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20(6):577-583.

- Richards JR, McGahan JP, Jones CD, et al. Ultrasound detection of blunt splenic injury. Injury. 2001;32(2):95-103.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Evidence Behind Focused Sonography for Trauma During Pregnancy”