Part 3 of a three-part series. Part 1 was published in the Nov. 2014 issue, and Part 2 was published in the Dec. 2014 issue.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 01– January 2015Interest in practicing and teaching emergency medicine around the world has increased exponentially. Many of our colleagues now have some international experience, many others dream of following a path to remote regions, and most academic centers are considering, if not running, fellowships related to international emergency medical care.

Yet most emergency physicians are unclear how to identify and evaluate global volunteer opportunities, what to expect when they travel to remote lands, and how to prepare for their experience. This article, the last of a three-part series based on The Global Healthcare Volunteer’s Handbook: What You Need to Know Before You Go, provides some of the basic information that emergency physicians need for these ventures.

Communication Issues: An Example

You arrived at the airport and, after a bit of confusion, got to your accommodations and found your way to the hospital, where you stepped into your role as a clinician/teacher. Your colleagues are friendly, but their English accents and vocabulary vary from what you are used to; you make do. However, although it is one of the country’s national languages, none of the patients speak English, so you’re working through makeshift interpreters, which is frustrating. A colleague helpfully suggests that you talk directly to the patient rather than to the interpreter, who should sit behind the patient (see Figure 1).1

“How about ‘zone’ for the patient?” asks the nurse. “Of course,” he continues, “we should probably give her some paracetamol and pethidine first.”

“Huh?” you weakly reply. The middle-age patient looks up at you with pleading eyes for some relief from her abdominal pain. What should you do?

Figure 1. Optimal medical interpreter positioning.

When working internationally, you expect to see unfamiliar diseases, unusual mechanisms of injury, novel medical and surgical techniques, and sparse equipment and supplies in resource-poor regions. However, you may not be ready to suddenly need to use multiple medications with which you have little or no experience or don’t immediately recognize.

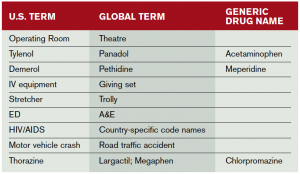

“Can you show me the medications?” you ask the nurse. He hands you the three vials, and the situation becomes clear. The nurse was using a combination of local medical slang (“zone” for ceftriaxone) and the internationally more common generic names for acetaminophen (paracetamol, often called Panadol, a common brand name) and meperidine (pethidine). (See Table 1 for more commonly confused terms.) Now that you understand, he asks how much parenteral paracetamol you want to give (a common route around the globe).

(click for larger image)

Table 1. Commonly Confused Medical Terms (English)

When conversing in a language other than English, the medical terms, especially abbreviations, will vary widely. Many of the following terms are used in countries where English is a common language among health care professionals, even if most of the population does not use it.

Once the patient is medicated, you begin running through the vast array of unusual diseases you have prepared to expect. You run down your list: scrub typhus, typhoid, malaria, dengue, chikungunya, leptospirosis, gastrointestinal tuberculosis, and hepatic parasites. After your physical exam and a bedside ultrasound, you find, as is usually the case, that your patient has a more common disease, appendicitis. Common diseases and injuries may present similarly everywhere in the world. While malaria, tuberculosis, dengue, and HIV are more common in some regions than others, cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, and trauma remain the most common causes of death around the world. Those are the ailments that you most often see and need to treat, albeit often with limited or makeshift resources.2

Daily Life and Culture

Of course, outside your clinical environment, you might find life considerably different than at home. On my travels, I have resided in tents (see Figure 2), shipping containers, hospital rooms, dormitories, hotels, houses (in bedrooms and dank basements), industrial buildings (between the noisy equipment), and on ships, both at dock and in rolling seas. Occasionally, I have slept alone. More often, I have had between one and about 250 roommates, many of whom snored loudly enough to “wake the dead.” Bathing and toilet facilities are usually shared and are often of strange design.

Finally, be prepared, especially after prolonged stays in resource-poor environments, to experience reentry culture shock when returning home. Initially, many daily activities that you take for granted will seem superfluous, if not decadent. Many ED patients will appear to have trivial complaints compared to many patients you saw abroad. Your first impulse may be to lecture them about the medical situation around the world. Restrain yourself! They are simply responding to their cultural norms. Reacquaint yourself with them. To help you, read a bit about reentry culture shock and how to prevent it before you initially leave on your trip; ask your loved ones, your boss, and a few colleagues to do the same. Then slowly allow yourself to reacclimate to your society and reflect on your joy and what you learned from your international experience.

Dr. Iserson is a fellow of the International Federation for Emergency Medicine and professor emeritus in the department of emergency medicine at The University of Arizona in Tucson.

References

- Iserson KV. The Global Healthcare Volunteer’s Handbook: What You Need to Know Before You Go. Tucson, AZ: Galen Press, Ltd. March 2014.

- Iserson KV. Improvised Medicine: Providing Care in Extreme Environments. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publishing. December 2012.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “What to Expect at Your Global Health Care Volunteer Destination”

April 28, 2015

EricaTherefore the dental implant, slight discomfort can be relieved with over-the-table pain medicines, for example Tylenol or Motrin.