A 21-year-old patient presents to the emergency department with complaints of dysuria a week following exposure to a new sex partner. She has increased vaginal discharge on exam and is empirically treated for gonorrhea and chlamydia. After her ED visit, the test results are positive for gonorrhea, so the department’s follow-up nurse fills out the communicable disease reporting form to the health department.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 05 – May 2021Meanwhile, the patient has talked to her partner about the diagnosis and urges him to seek care. Because he is asymptomatic and concerned about the cost of care, he does not get tested. A month later, the patient is reinfected by her untreated partner. This time, she waits to go to the emergency department because she is embarrassed. She finally presents with pelvic inflammatory disease and a tubo-ovarian abscess, requiring admission to the hospital.

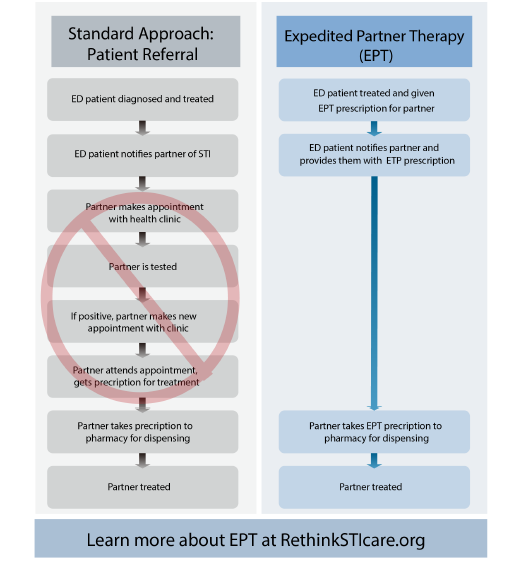

This case represents many others that are examples of preventable morbidity. The emergency department might have helped avoid this outcome if it had provided the patient with antibiotics for her partner via expedited partner therapy (EPT). EPT is the practice of treating the partners of patients diagnosed with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) if their partners are unlikely to seek timely care. In the era of increased awareness of transmissible diseases and health equity, the time has come for emergency medicine to embrace EPT.

STIs Are a Hidden Public Health Crisis

Though the COVID-19 pandemic has seized the world’s attention to the threat of communicable diseases for the past year, the United States’ STI epidemic has been intensifying unchecked for the past decade. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated one in five Americans had an STI on any given day in 2018.1 From 2014 to 2018, the incidence of gonorrhea rose 63 percent, and chlamydia rose 19 percent to 1.8 million cases, the most chlamydia cases ever reported to the CDC.2

STIs are not just a problem for the American health care system; they are a specific issue for the emergency department. STI visits in the emergency department have been outpacing the general rise in all-cause ED visits.3 In certain cities, emergency departments have had a substantial increase in positive tests, with higher positivity rates than outpatient settings.4 Emergency departments see a disproportionate share of STI cases compared to other health care settings. On a national level, in 2018, emergency departments diagnosed similar proportions of all gonorrhea cases as STD clinics.5

Moreover, STIs are an issue of social justice and health equity. STIs disproportionately affect those with low health care access, racial minority and minoritized populations, and low-income populations, the same vulnerable populations that are more likely to use the emergency department for STI care.6,7 Additionally, young males without primary care access are more likely to seek care in ED settings, representing an opportunity for EPT of male partners to improve women’s reproductive health via the prevention of STI complications, including future infertility and pregnancy complications.

Adding to the urgency to stop the STI epidemic, antimicrobial resistance for gonorrhea is increasing. In December 2020, for the first time in a decade, the CDC revised its treatment guidelines for gonococcal infections.8 Among other changes, these updates recommended: 1) doubling the recommended cephalosporin doses both for parenteral treatment and pill-based therapy and 2) replacing azithromycin for concurrent treatment of suspected chlamydia with doxycycline when treating empirically for gonorrhea. These changes were made due to increasing azithromycin resistance and concerns for antimicrobial stewardship.

Why Use EPT?

The good news is the emergency department can play an important role in curbing the STI public health crisis by using a tool readily at our disposal: EPT.9 EPT has proven effective at breaking the cycle of STI reinfection. In a meta-analysis, EPT reduced reinfection rates by 29 percent and increased the number of partners treated per patient compared to telling the patient to have their partner treated (ie, simple patient referral).10

In addition to being efficacious, patients want EPT. In STD clinics, 69 percent of patients accepted EPT when offered.11 EPT is legally protected or permissible in 46 states and potentially allowed in four states.12 EPT has a history of broad-based support by the CDC, American Osteopathic Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American Bar Association.13 In the 2020 ACEP Council meeting, ACEP joined these organizations in official support of EPT.14

The State of EPT in the ED

Despite the potential for EPT to help stop the spread of STIs, the practice is not yet widely used in emergency departments. Studies have identified a need to increase awareness and education among outpatient clinicians. This knowledge gap is magnified in the emergency department, where the practice has received little attention both at the training and practice levels. In a national survey of medical directors in academic emergency departments, only 19 percent reported their department had implemented EPT. Moreover, departmental uptake of its use was uneven; some physicians did not realize EPT was even legal within the reported implementer sites. Despite low awareness, there is enthusiasm for EPT: About half (56 percent) of those surveyed thought their department would support EPT, and most (79 percent) personally supported EPT. These findings demonstrate there is room for growth in the national implementation of ED-based EPT.

What Can You Do?

What are some things you can do as an individual to implement EPT in your department? Begin by checking the legal status of EPT in your state. The CDC’s website provides recent guidelines by state (www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal), and state health departments often have guidance for clinicians and patient information sheets. If the legal status of EPT is not specified by your state’s laws, work with your state ACEP chapter to lobby for this public health intervention at your next state advocacy day. If EPT is not explicitly legally protected in your state like it is in some states, advocate that your legislature promote clarity around ambiguous laws to protect prescribers from legal liability. If your state supports it, determine the specific prescribing guidelines and refer your patients locally for follow-up testing and partner treatment.

Figure 1: Standard therapy versus expedited partner therapy for sexually transmitted infections.

Note that prescribing guidelines vary by state. Some require the name of the patient or partner on the prescription, while in others you can simply prescribe to the name “Expedited Partner Therapy.” Likewise, different states have varying legal requirements regarding what information must be provided along with EPT, such as specific information sheets to hand to the patient.

Once you have confirmed your state supports EPT prescribing, you can take action at a local level. To improve the overall care for STIs, advocate that your department use rapid tests to improve the accuracy of empiric treatment.15 Though EPT can still be offered empirically based on clinical diagnosis before lab confirmation, rapid testing can aid in the precision of selecting which patients should be offered EPT at the primary visit.

Help educate your colleagues and potential prescribers by giving a presentation at your departmental or faculty meetings. Meet with key stakeholders (eg, medical directors, nursing, pharmacy, electronic health record builders, informatics officers, hospital legal counsel, etc.) to determine what orders and policies work best for your group. For patients identified as positive during lab follow-up, work with your medical director and follow-up office (eg, nurse, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, etc.) to create straightforward protocols for offering EPT after lab confirmation. For tips and tools on starting EPT at your emergency department, check out this website designed by emergency physicians: www.RethinkSTIcare.org.

EPT is not a process that will happen on its own in the emergency department. But by learning about EPT and becoming a departmental champion, you can take the critical first step in moving emergency medicine toward improving the sexual and reproductive health of our patients.

Dr. Solnick is a fellow in the National Clinical Scholars Program at the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation and a clinical lecturer in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Dr. Solnick is a fellow in the National Clinical Scholars Program at the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation and a clinical lecturer in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Dr. Fleegler is associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

Dr. Fleegler is associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

Dr. May is professor of emergency medicine and director of emergency department antibiotic and outpatient stewardship at UC Davis Health in Sacramento.

Dr. May is professor of emergency medicine and director of emergency department antibiotic and outpatient stewardship at UC Davis Health in Sacramento.

Dr. Kocher is associate professor in the departments of emergency medicine and learning health sciences at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Kocher is associate professor in the departments of emergency medicine and learning health sciences at the University of Michigan.

References

- CDC estimates 1 in 5 people in the U.S. have a sexually transmitted infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- New CDC report: STDs continue to rise in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed March 30, 2021.

- Pearson WS, Peterman TA, Gift TL. An increase in sexually transmitted infections seen in U.S. emergency departments. Prev Med. 2017;100:143-144.

- Batteiger TA, Dixon BE, Wang J, et al. Where do people go for gonorrhea and chlamydia tests: a cross-sectional view of the central Indiana population, 2003–2014. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46(2):132-136.

- Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Brackbill RM, Sternberg MR, Fishbein M. Where do people go for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases? Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31(1):10-15.

- Ware CE, Ajabnoor Y, Mullins PM, et al. A retrospective cross-sectional study of patients treated in US EDs and ambulatory care clinics with sexually transmitted infections from 2001 to 2010. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(9):1808-1811.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(50):1911-1916.

- HHS releases first national strategic plan to address sexually transmitted infections. US Department of Health and Human Services website. Accessed March 30, 2021.

- Ferreira A, Young T, Mathews C, et al. Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD002843.

- Vaidya S, Johnson K, Rogers M, et al. Predictors of index patient acceptance of expedited partner therapy for Chlamydia trachomatis infection and reasons for refusal, sexually transmitted disease clinics, New York City, 2011 to 2012. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(11):690-694.

- Legal status of expedited partner therapy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- Expedited partner therapy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- 2020 ACEP Council resolutions. ACEP Now. 2020;39(12):16.

- May L, Ware CE, Jordan JA, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the treatment of patients tested for chlamydia and gonorrhea after a rapid polymerase chain reaction test versus standard of care testing. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(5):290-295.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

4 Responses to “Expedited Partner Therapy Can Stop Sexually Transmitted Infections”

June 20, 2021

Gary RobertsTreatment of partners in the setting of STIs is medically appropriate. This article did not address the pitfalls of prescribing medication for an unknown and unseen patient whose medical history cannot be confirmed. Anaphylaxis to cephalosporins is well known and there are numerous medications with potential adverse interactions with azithromycin.

As a physician, I am unwilling to subject an unknown patient to potential harm and am equally unwilling to incur the legal liability attached to an adverse outcome in this situation no matter how noble the cause. (health care equity)

The (potential) patient has the responsibility in this case. ED physicians are neither qualified nor justified to act “in loco parentis” for the community.

June 20, 2021

TWhat if partner has an allergy or adverse drug reaction. You never did a formal evaluation. Is their sovereign immunity?

June 21, 2021

Matt JaegerHow do you propose we prescribe medications to a patient we don’t have a chart for, don’t have a relationship with, haven’t performed a history on, and don’t know what their allergies are? This seem like a risk I’m not willing to take. I don’t think I’m willing to start handing out prescription to unknown individuals.

At some point, patients must take at least partial responsibility for their care and initiate a relationship with a medical provider, be it in an ER, public health clinic, walk-in clinic or a PCP.

June 21, 2021

Gary Roberts, MD, JDWhile “social justice and health equity” are noble motives and lofty goals, the reality of EPT is far more gritty.

Even granting the supposition that there may be some legal protection for the prescribing physician, what protection is there for the unexamined and unseen patient?

Cephalosporins are well-known to have a not insignificant allergic/anaphylactic profile. The myriad potential drug interactions and adverse reactions with doxycyline are well documented.

Nonetheless, the EPT approach is to expose patients to these risks without their consent and lacking any first-hand knowledge of their medical condition.

It is neither the province nor the responsibility of Emergency Medicine to act in loco parentis in these situations. The patient must bear some responsibility.

“Social justice and health equity” in this context is already being well-served. There are numerous free clinics for the treatment of STI.

https://www.yourstdhelp.com/free_clinic_locator.html

Noble motives and the possibility of legal protection are flimsy and totally inadequate excuses to expose unknown patients to significant risks.