Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 04 – April 2019Ever since the release of direct-acting oral anticoagulants, emergency physicians have been tasked with managing their associated complications. The introduction and initial popularity of dabigatran caught us lacking, with no useful options for managing hemorrhage. A specific antidote was not available, nor was a factor replacement strategy clearly efficacious. This situation has been improved with the availability of idarucizumab, the monoclonal antibody for reversal of dabigatran.1 We hope this antidote will produce clinically meaningful hemostasis following administration, but unfortunately, the best data available come to us from a single-arm trial.

ANNEXA-4 Results

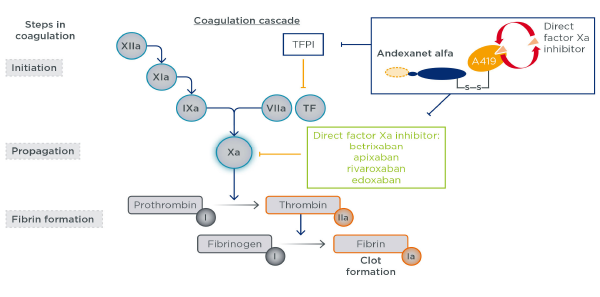

Now, in a similar fashion, the full cohort results from the Andexanet Alfa, a Novel Antidote to the Anticoagulation Effects of FXA Inhibitors (ANNEXA-4) study have been released to great fanfare at the 2019 International Stroke Conference, with simultaneous publication in The New England Journal of Medicine.2 This, like the Study of the RE-VERSal Effects of Idarucizumab on Active Dabigatran (RE VERSE-AD), details the efficacy of andexanet alfa as a reversal agent for the factor Xa inhibitors (eg, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, and enoxaparin). Rather than a monoclonal antibody like idarucizumab, andexanet alfa is a modified, recombinant human factor Xa molecule. The mechanism of reversal then is a greater affinity for the various factor Xa inhibitors than human native factor Xa. Displacing factor Xa inhibitors from native factor Xa contributes to normalization of the coagulation cascade, allowing for subsequent clot formation.

Another important difference is in the practical use of andexanet. Idarucizumab practically irreversibly binds dabigatran and leads to excretion of the idarucizumab-dabigatran complex without prominent rebound phenomena. Andexanet, in contrast, has a much shorter half-life and is administered as a bolus and a two-hour continuous infusion. In ANNEXA-4, monitoring of anti–factor Xa activity demonstrated profound improvement immediately following completion of the bolus. While this improvement was sustained through the end of the two-hour infusion protocol, by four hours after initiation of the bolus, anti–factor Xa activity had rebounded dramatically.

These characteristics complicate evaluation of ANNEXA-4 and its true clinical utility. The underlying hypothesis driving clinical efficacy relates to the restoration of factor Xa activity during the infusion, thus leading to new clot formation and stabilization. This leads to the core leap of faith required with andexanet: The clot will theoretically remain stable and provide clinically meaningful hemostasis following cessation of andexanet, even when anti–factor Xa levels rise above therapeutic thresholds. This also suggests important considerations for follow-up care, as any urgent surgical procedures performed after cessation of the andexanet infusion will not benefit from any hemostatic activity.

It is not all bad news from the andexanet camp in ANNEXA-4. Of the 254 patients evaluated for efficacy, 204 (82 percent) were judged to have “good” or “excellent” hemostatic efficacy. Unfortunately, these hemostatic surrogates are not clearly tied to patient-oriented outcomes. For example, approximately two-thirds of the bleeding sites included were intracranial hemorrhage. At this site, “good” or “excellent” hemostasis required an increase in maximum thickness of ≤35 percent at a 12-hour follow-up assessment. The logical follow-up questions are, is this good—or excellent—enough, and how much of this hemostasis can be attributed to andexanet?

Evaluating “Good” Against Alternatives

This brings us to the elephant in the room: the lack of any meaningful comparison arm. While those designing this study seemed to feel that a control arm was unwarranted or unethical, there is an obvious and clear alternative available, prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC). The most typically used four-factor PCCs include factors II, VII, IX, and X, along with proteins C and S. While PCCs are indicated primarily for the urgent reversal of vitamin K antagonists, they are also recommended, by guidelines, for the treatment of anti–factor Xa–related hemorrhage.3 Should the specific but finite nature of andexanet make it the preferred approach, or do we need a prospective comparison with PCCs to determine its utility?

Figure 1: Andexanet alfa mechanism of action

Andexanet alfa is a recombinant modified FXa protein with no enzymatic activity, designed to bind and sequester FXa inhibitors and thus reverse anticoagulation.

EMJ Cardiol. 2018;6(1):47-51. CC-BY NC 4.0

The answer is clearly the latter, as plans for such a study are already underway (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT03661528). While cost and value assessments are difficult when faced with life-threatening complications, it is recognized by all parties that we need additional data to determine when, or if, andexanet should be used. The costs of PCCs are already imposing, with a typical dose priced around $5,000. Andexanet takes this to another level, with the cost up to $50,000 for the high-dose protocol.4 While these costs may be comparable to other lifesaving therapies and interventions, it is an impressive ask to consider this therapy without data demonstrating its clinical superiority over an alternative a tenth the cost.

It should also be noted that nearly 30 percent of those in this trial treated with andexanet were ultimately excluded from the efficacy analysis, owing primarily to anti–factor Xa levels lower than the prespecified threshold requiring treatment. The lack of reliable initial tests to verify the presence of deranged coagulation is not unique to the factor Xa inhibitors, but it is decidedly unpalatable to consider the extent to which patients may be unnecessarily treated with this expensive therapy.

Finally, although the primary concern is comparative efficacy to care with PCCs, there is also concern regarding adverse effects. Andexanet does not only bind anti–factor Xa but also tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI). Without rehashing everyone’s favorite coagulation cascade from medical school, the “inhibitor” portion of TFPI prevents unwanted coagulation. Animal studies conducted by the manufacturer suggest andexanet binding TFPI should not result in excess adverse effects, specifically in those patients who might be inadvertently treated. However, these conclusions cannot be confirmed or refuted by those data.5 Overall, 10 percent of those treated with andexanet developed a thrombotic event within 30 days, half of which were arterial (eg, stroke or myocardial infarction). While PCCs are not free of associated thrombotic harms, this safety comparison is also critical to the follow-up clinical trial.

In the meantime, until clearer data arrive, andexanet is best left on the sidelines. Furthermore, by the time the follow-up trial is conducted, consideration of andexanet may be moot, as its competitor, ciraparantag, is on the horizon.6 Preclinical data suggest this molecule may be a universal antidote to all heparins and oral anticoagulants, but as we’ve seen with andexanet, it is no small feat to live up to the hype.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of Dr. Radecki and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or academic affiliates.

References

- Pollack CV Jr, Reilly PA, van Ryn J, et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-441.

- Connolly SJ, Crowther M, Eikelboom JW, et al. Full Study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors (published online ahead of print Feb. 7, 2019). N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1814051.

- Frontera JA, Lewin JJ 3rd, Rabinstein AA, et al. Guideline for reversal of antithrombotics in intracranial hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and Society of Critical Care Medicine. Neurocrit Care. 2016;24(1):6-46.

- Andexxa— an antidote for apixaban and rivaroxaban. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2018;60(1549):99-101.

- Lu G, Lin JP, Curnutte JT, et al. Effect of andexanet-TFPI interaction on in vitro thrombin formation and coagulation markers in the TF-pathway. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl. 1):629.

- Ansell JE, Bakhru SH, Laulicht BE, et al. Single-dose ciraparantag safely and completely reverses anticoagulant effects of edoxaban. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(2):238-245.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Factor Xa Inhibitor Reversal Agent Is Not Ready for Prime Time”