From 2002 to 2017, there has been more than a fourfold increase in the total number of opioid-related deaths, with more than a sevenfold increase in heroin overdose deaths and a 22-fold increase in synthetic opioid overdose deaths in the United States.1 Hospital billing data from 2014 suggest that more than 90,000 emergency department patients presented with visits for unintentional, nonfatal opioid overdoses.2 And the prevalence of suspected opioid overdose–related ED visits has significantly increased recently as well.3

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 01 – January 2019Why does this matter to emergency physicians?

Because ED visits related to opioid use provide the perfect opportunity to start patients on treatment and kick-start their path to recovery. Many of these patients have no other access to health care, and patients are more likely to become opioid-free when treated and counseled appropriately after an opioid-related illness.

And along with the recent trends in opioid-related deaths, we’ve seen a parallel development in improved care of patients with the use of the partial opioid agonist buprenorphine-naloxone. This treatment modality has only recently been studied in emergency departments, and evidence suggests buprenorphine-naloxone decreases mortality, improves withdrawal symptoms, decreases drug use, improves follow-up rates, and decreases crime rates.4–7 Therefore, it is now more important than ever that all emergency medicine providers take on the responsibility of learning about this lifesaving medication and implement it in their practices.

Recognizing Opioid Withdrawal

The clinical features of opioid withdrawal overlap with severe gastroenteritis—symptoms include crampy abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle aches, chills, and diaphoresis—making it easy to confuse the two. Opioid withdrawal’s distinguishing features include watery eyes and nose, severe insomnia, gooseflesh, mydriasis, anxiety, restlessness, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Opioid withdrawal is rarely life-threatening. However, it may precipitate preterm labor in pregnant patients and acute coronary syndrome in patients with coronary artery disease, and there are published case reports of temporally-related Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.8

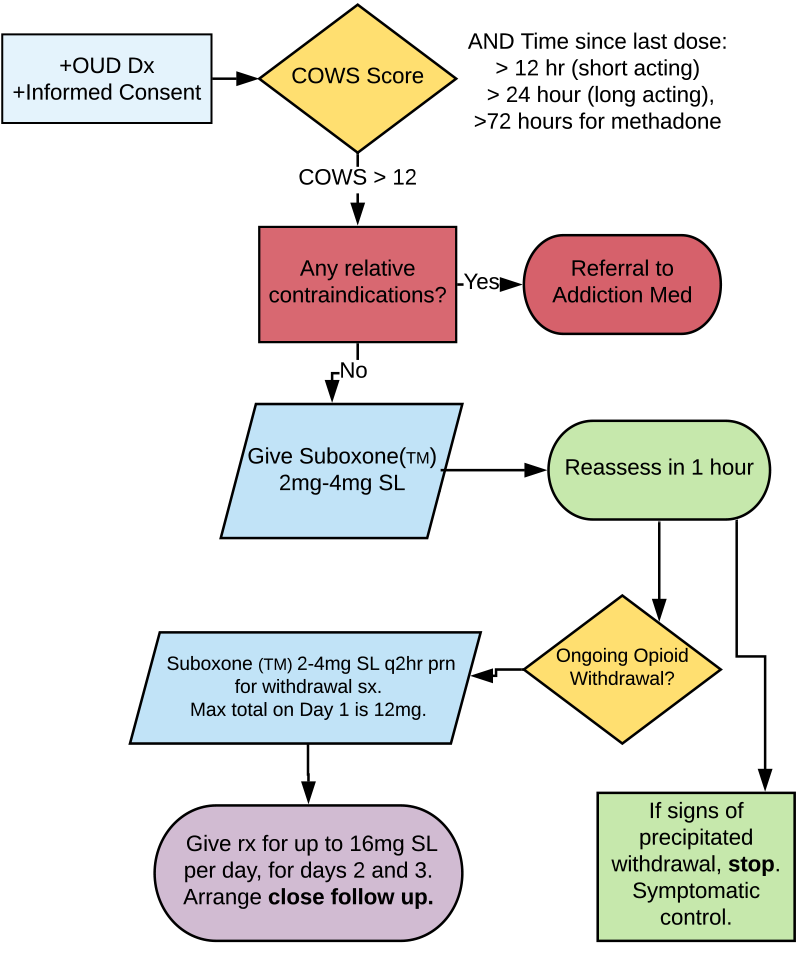

The various opioids feature a wide range of half-lives, ranging from a few hours with fentanyl to several days with methadone. Even after just five days of taking an opioid, physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms may develop upon cessation. Consider these five steps when prescribing opioids from the emergency department, and counsel patients appropriately (see Figure 1 for a flowchart of this process).

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Assessing and Treating Opioid Withdrawal & Opioid Use Disorder

OUD = opioid use disorder; COWS = clinical opioid withdrawal scale.

Credit: Taryn Lloyd

Step 1: Does the Patient Meet Criteria for Opioid Use Disorder?

Patients must meet at least two of the following criteria in a 12-month period to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for opioid use disorder.9

- Opioids are often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects.

- Opioid cravings are experienced.

- Recurrent opioid use results in failure to fulfill major obligations at work, school, or home.

- Continued opioid use occurs despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of opioid use.

- Recurrent opioid use occurs in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Continued opioid use occurs despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- Exhibits tolerance.

- Exhibits withdrawal.

Step 2: Assess Readiness to Quit

What are the patient’s goals? Are they ready and willing to start treatment in hopes of stopping their opioid use? Use the Readiness Ruler to assess the stage of change (example question: “On a scale of 1 to 10, how ready are you to make a change today?”).10 Obtain informed consent before starting buprenorphine-naloxone in the emergency department. If the patient is not ready to start the medication, share your concerns about their ongoing opioid use, the risk of overdose and medical complications, and harm-reduction techniques (eg, a naloxone kit, clean needles, etc.).

Step 3: Assess the Severity of Opioid Withdrawal Using COWS

Use the validated assessment tool Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) to determine the withdrawal severity.11 This scale is similar to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment scale used for alcohol withdrawal and is easily administered by ED staff. Points are assigned for the signs and symptoms of withdrawal (eg, tachycardia, sweating, restlessness, enlarged pupils, bone/joint aches, runny nose/tearing, upset gastrointestinal, tremor, yawning, anxiety/irritability, and gooseflesh). A score of 5–12 = mild, 13–24 = moderate, 25–36 = moderately severe, and greater than 36 = severe.

Patients must score at least in the moderate range to be eligible for buprenorphine-naloxone therapy.

Step 4: Buprenorphine-Naloxone and Withdrawal Symptom Treatment

Relative contraindications to buprenorphine-naloxone initiation include allergy to either buprenorphine or naloxone, hepatic dysfunction, current respiratory distress, decreased level of awareness currently, concurrent active alcohol use disorder, and concurrent benzodiazepine use.

Suboxone is buprenorphine and naloxone in a sublingual tablet. Naloxone is not active unless injected; it is a taper-resistance medication. Buprenorphine is a partial agonist that acts on the opioid mu receptor. It has a high binding affinity but only partial intrinsic activity on the receptor. This means it is effective for pain and withdrawal but features less risk of respiratory depression and side effects than pure opioids.

Step 5: Counsel and Arrange Appropriate Follow-up

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is a valuable tool to start patients on the path to recovery. In one study, 37 to 45 percent of patients who underwent SBIRT in the emergency department engaged with treatment at 30 days.12 Ask for permission to discuss substance use and overdose, discuss goals, and express your concerns with their current use. Screen for other substance use.

Screen for safety as well. The opioid overdose could represent a suicide attempt. Assess the patient’s goals and stage of change. Offer referral to resources in the community or hospital, based around goals (eg, housing, detox, addiction medicine clinic, family doctor services, safe injection facilities, etc.). Discuss and offer naloxone kits and clean injection supplies. Counsel patients around the high risk of accidental overdose given withdrawal and/or decrease in tolerance.

Finally, arrange rapid follow-up in an addiction medicine clinic or similar community clinic in one to two days if possible. Provide a prescription for daily observed dosing at a pharmacy at the appropriate dose up to 16 mg SL per day until follow-up.

All patients are more than their addiction. We have a significant opportunity to improve the lives of patients with opioid use disorders in the long run.

Special thanks to Dr. Aaron Orkin, Dr. Michelle Klaiman, and Dr. Kathryn Dong for their contributions to the EM Cases podcast that inspired this article and to Dr. Taryn Lloyd for the creation of the opioid withdrawal management algorithm diagram used in this article.

References

- Overdose death rates. National Institute on Drug Abuse website. Accessed Dec. 19, 2018.

- Annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes—United States, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed Dec. 19, 2018.

- Vivolo-Kantor AM, Seth P, Gladden RM, et al. Vital signs: trends in emergency department visits for suspected opioid overdoses—United States, July 2016–September 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(9):279-285.

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department–initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636-1644.

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550.

- Molero Y, Zetterqvist J, Binswanger IA, et al. Medications for alcohol and opioid use disorders and risk of suicidal behavior, accidental overdoses, and crime. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(10): 970-978.

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD002207.

- Olson PC, Agarwal V, Lafferty JC, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy precipitated by opiate withdrawal. Heart Lung. 2018;47(1):73-75.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: 2013.

- Hesse M. The Readiness Ruler as a measure of readiness to change poly-drug use in drug abusers. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:3.

- Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003; 35(2):253-259.

- Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, et al. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1-3):280-295.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Five Steps to Help You Manage Opioid Use Disorder Patients”