Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 11 – November 2021Last month we debunked five myths about trauma and triage in older patients—the fastest growing population in the United States.1 This month we’ll look at falls and other common injuries.

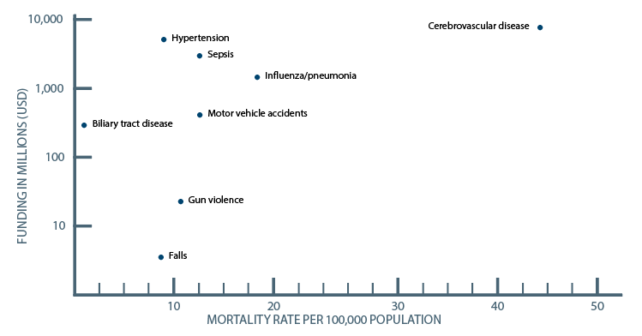

Older adults with severe injuries represent at least 40 percent of all adults with severe injuries.2 Ground-level falls are the most common mechanism of injury in older patients and carry a 10-fold higher mortality rate.3 Research funding to study falls, relative to their associated mortality, is much lower than comparable conditions—including firearm deaths (see Figure 1).4 Older trauma patients with falls are often undertriaged at the ED triage as well as to regional trauma centers.5-8

Myth 6: Unstable C-Spine Injuries Are Unlikely After Ground-Level Fall

Older patients are more likely to sustain fractures (especially vertebral fractures) at much lower forces due to osteoporosis and reduced bone mass. Half of cervical spine injuries in older patients are considered unstable and older patients are at higher risk for central and anterior cord syndromes.9 Any older trauma patient who is undergoing a head CT to rule out traumatic brain injury should also be considered for cervical spine imaging.

Myth 7: Anticoagulant Medications Should Always Be Withheld After Minor Head Injury in Older Patients

While anticoagulants should certainly be withheld after major head injury with evidence of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage, cessation of anticoagulation is unnecessary following an ED visit for minor head injury without evidence of intracranial hemorrhage.10 In the context of warfarin for primary stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation, observational data suggest that a person would need to fall 295 times in one year for the risk of a subdural hemorrhage to outweigh the benefits of warfarin therapy.11 This risk-benefit ratio would predictably be even more favourable for direct oral anticoagulants since they have been shown to carry a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than warfarin.12

Myth 8: Isolated Rib Fractures Are Benign Injuries That Do Not Require Treatment

Frailty is one of the strongest predictors of mortality following rib fractures, and mortality increases proportionally with each additional rib fracture.13 Rib fractures are a surrogate marker for polytrauma—observational data suggest that 81 percent of patients with rib fractures have additional associated traumatic injuries.14 CT is the imaging modality of choice, as chest X-ray has been shown to miss up to 50 percent of rib fractures. There is a higher incidence of pulmonary contusions, pneumonia, and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation in older patients with rib fractures. It is prudent to have a low threshold to order a CT of the abdomen to rule out solid organ injury that also has a higher incidence in older patients who have sustained rib fractures.15 Consider transfer to a regional trauma center for older patients with three or more rib fractures, bilateral rib fractures, flail segment, or any rib fracture in an older patient with significant underlying pulmonary disease.16

Myth 9: Hip Fractures Do Not Require Urgent Surgery

Observational studies suggest that delays to surgery for hip fractures are associated with higher 30-day mortality, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia.17 The recent HIP Fracture Accelerated Surgical TreaTment And Care tracK (HIP ATTACK) randomized controlled trial compared time to surgery of less than six hours versus usual care and found a lower rate of delirium, stroke, infection, and urinary tract infection.18 It is incumbent upon the emergency physician to help facilitate timely transfer to the operating room for all patients requiring surgery for hip fractures.

Myth 10: Older Patients Who Are Discharged from the ED with a Non-injurious Fall Do Not Require Specific Follow-up Assessments

Persons with single non-injurious falls who have normal gait and balance are considered at low risk for recurrent falls. Older patients who present to the emergency department after a fall should have a quick gait and balance assessment completed in the emergency department. Time-efficient validated assessment tools include the timed up and go test and the modified 30 second sit to stand test.19,20 Patients at high risk for recurrent falls include those with a fall resulting in injury, a gait or balance disorder, two or more falls in the past 12 months or a Clinical Frailty Scale of 4–9.21 All such patients should be considered for evidence-based fall-reduction management, including referral for an occupational therapy home safety assessment, falls prevention program, and communication with the primary care physician to conduct a full fall risk assessment and screen for conditions predisposing to injurious falls, such as osteoporosis.22

A special thanks to Dr. Barbara Haas, Dr. Bourke Tillman, and Dr. Camilla Wong for their expert contributions to the EM Cases podcast from which this article was inspired.

References

- Sciubba JD. Population aging as a global issue. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. Accessed Sept. 9, 2021.

- Min L, Burruss S, Morley E, et al. A simple clinical risk nomogram to predict mortality-associated geriatric complications in severely injured geriatric patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(4):1125-1132.

- Spaniolas K, Cheng JD, Gestring ML, et al. Ground level falls are associated with significant mortality in elderly patients. J Trauma. 2010;69(4):821-825.

- Stark DE, Shah NH. Funding and publication of research on gun violence and other leading causes of death. JAMA. 2017;317(1):84-85.

- Lenartowicz M, Parkovnick M, McFarlan A, et al. An evaluation of a proactive geriatric trauma consultation service. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):1098-1101.

- Nakamura Y, Daya M, Bulger EM, et al. Evaluating age in the field triage of injured persons. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(3):335-345.

- Caterino JM, Brown NV, Hamilton MW, et al. Effect of geriatric-specific trauma triage criteria on outcomes in injured older adults: a statewide retrospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):1944-1951.

- Uribe-Leitz T, Jarman MP, Sturgeon DJ, et al. National study of triage and access to trauma centers for older adults. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(2):125-135.

- Jeanmonod R, Varacallo M. Geriatric cervical spine injury. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Huang GS, Dunham CM, Chance EA, et al. Detecting delayed intracranial hemorrhage with repeat head imaging in trauma patients on antithrombotics with no hemorrhage on the initial image: a retrospective chart review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2020;220(1):55-61.

- Cheng HY. Is age a risk factor for warfarin-related major bleeds in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1155.

- Foerch C, Lo EH, van Leyen K, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage formation under direct oral anticoagulants. Stroke. 2019;50(4):1034-1042.

- Marini CP, Petrone P, Soto-Sánchez A, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with rib fractures [published online ahead of print Jul. 19, 2019]. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019.

- Schweitzer AD, Niogi SN, Whitlow CT, et al. Traumatic brain injury: imaging patterns and complications. Radiographics. 2019;39(6):1571-1595.

- Bhattacharya B, Fieber J, Schuster K, et al. “Occult” rib fractures diagnosed on computed tomography scan only are still a risk factor for solid organ injury. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2015;8(3):140-143.

- Kim M, Moore JE. Chest trauma: current recommendations for rib fractures, pneumothorax, and other injuries. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2020;10(1):61-68.

- Pincus D, Ravi B, Wasserstein D, et al. Association between wait time and 30-day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery. JAMA. 2017;318(20):1994-2003.

- The HIP ATTACK Investigators. Accelerated surgery versus standard care in hip fracture (HIP ATTACK): an international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2020;395(10225):698-708.

- Lyders Johansen K, Derby Stistrup R, Skibdal Schjøtt C, et al. Absolute and relative reliability of the timed ‘up & go’ test and ‘30 second chair-stand’ test in hospitalised patients with stroke. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165663.

- McAllister LS, Palombaro KM. Modified 30-second sit-to-stand test: reliability and validity in older adults unable to complete traditional sit-to-stand testing. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2020;43(3):153-158.

- Walston J, Buta B, Xue QL. Frailty screening and interventions: considerations for clinical practice. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(1):25-38.

- Moncada LV. Management of falls in older persons: a prescription for prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(11):1267-1276.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Geriatric Trauma Myths and Misperceptions: Part 2”