There is no shortage of guidelines, protocols, or quality measures across emergency medicine. Regardless of the domain, somewhere an expert panel has convened to issue a pronouncement informing all of the ideal care of patients under their specialty umbrella, indirectly extending to their care in the emergency department. A common limitation to many of these guidelines, however, is the lack of recognition of available resources or the unique challenges of certain patient groups. In an environment in which patients may have their entire work-up in the waiting room, or attend a critical access hospital staffed by non-emergency physicians, or lack the financial support to follow up with an appropriate specialist, a pragmatic approach to care is required.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 08 – August 2023This real-world pragmatism is the guiding principle embodied by the Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE) project, published by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Rather than focus on the narrow evidence supporting recommendations for a precisely diagnosed clinical syndrome, these guidelines try to create an expert consensus for the approach, as stated on their website, “to the care of the most common chief complaints that can be seen on the tracking board of any emergency department in the country.”1

To date, there have been three GRACE publications. The first describes approaches to chest pain, the second, abdominal pain, and the more recent third, vertigo.2-4 A fourth is planned for publication in late 2023, and will address non-opioid substance dependence. Each of these chooses a set of practice-based questions and applies the grading of recommendations assessment development and evaluation (GRADE) methodology, a framework for rating the quality of the best available evidence and developing clinical practice recommendations.

The first, GRACE-1, addresses adult patients with “recurrent, low-risk chest pain,” a patient population commonly encountered in emergency departments. The specific recommendations from this publication have already been covered in a prior issue by Lauren Westafer, DO, MPH, MS, with an overview of the mixed-strength clinical guidance across the spectrum of chest-pain representations.5 An important theme, however, begins to emerge regarding how little evidence directly informs a substantial fraction of clinical practice, and the extent to which we rely on indirect generalization.

The second, GRACE-2, addresses adult patients with “low-risk, recurrent abdominal pain” in the emergency department. While “low-risk” chest pain is more easily described using scoring systems, undifferentiated abdominal pain is less well-defined. In this instance, the authors describe a population based in sensible clinical judgement, including an absence of trauma, recent abdominal surgery, cancer, and concerning physical findings.

However, unlike with chest pain, there are far fewer industry partners performing research tied to marketing new imaging technology or diagnostic assays. The net result is an even more disappointing spectrum of recommendations than in GRACE-1. For example, addressing the common question regarding the necessity of repeat CT scanning in this “low-risk” population, the authors could not find any relevant evidence, and were therefore unable to formulate any recommendation regarding imaging avoidance on a subsequent visit. The authors did make conditional recommendations based on “very low certainty of evidence” regarding avoidance of ultrasound following a normal CT scan, and, as in recurrent chest pain, consideration of depression or anxiety screening for patients with intractable recidivism. In spite of lack of evidence, the authors make a very reasonable recommendation of good clinical practice to avoid treating with opiates when feasible.

The third, GRACE-3, garnered a greater measure of controversy. These guidelines address the approach to acute dizziness and vertigo in the ED; they diverge from the preceding two guidelines. The most striking difference is the number of recommendations, 14, published along with several bespoke, companion, systematic reviews informing the recommendations. GRACE-3 also includes substantially more educational content relevant to the approach to acute dizziness in the ED, breaking down the important diagnoses and their clinical features. There is, finally, dramatically better evidence informing these guidelines, with several recommendations carrying “high certainty of evidence.”

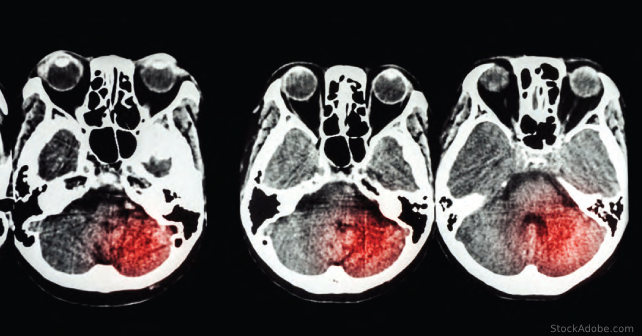

Those recommendations with “high certainty” pertain primarily to the use of advanced imaging in the diagnostic approach to acute dizziness. Importantly, these authors strongly recommend against the use of either non-contrast CT or CT angiography of the brain to distinguish between a central or peripheral cause for dizziness. Due to its wide availability and accessibility in most EDs, the allure of ordering a CT in the context of possible intracerebral pathology runs high. However, fewer than one percent of patients with dizziness will have a cause identified on CT, virtually all of whom have additional neurologic findings. The consideration to use CT for exclusion of intracranial hemorrhage is noted to be unfounded, as patients with intracranial hemorrhage do not typically present with complaints of isolated vertigo or dizziness.

Many of the other recommendations, however, are enmeshed with the primary controversial issue in this guideline. The core element of the guideline is promotion of the head impulse, nystagmus, and test of skew (HINTS) examination. There is high certainty of evidence that clinicians trained in the HINTS examination are able to distinguish between central and peripheral causes of dizziness. Unfortunately, the training element is key, as there is ample evidence that clinicians who have not undertaken any special training are not able to apply HINTS correctly. Therefore, the authors of GRACE-3 call for wide training of the EM workforce in the use of HINTS.

The implication of such a call is magnified by the scope of the training. In the studies in which clinicians accurately applied the HINTS examination, the training consisted of an initial six hours of lectures and workshops which was repeated seven months later. It is costly to ask the entire emergency-medicine workforce to undergo specialized training with an in-person workshop, let alone a second, followup episode. There is no evidence yet whether other training frameworks are adequate, nor is there evidence to inform the frequency or intensity with which HINTS skills require reinforcement. Absent an easier path forward for upskilling the workforce, the reliance of GRACE-3 on HINTS to inform its practice recommendations limits its present real-world application.

These are just the initial pieces of work under the banner of attempting to inform “reasonable” care in the emergency department. The most striking aspect of most of this work is how little evidence directly informs the sorts of decisions facing clinicians every day. Having identified these gaps provides a road map for future research, and one hopes some of these questions can be revisited in the future with more robust recommendations.

Dr. Radecki is an emergency physician and informatician with Christchurch Hospital in Christchurch, New Zealand. He is the Annals of Emergency Medicine podcast co-host and Journal Club editor and can be found on Twitter @emlitofnote.

References

- Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. About SAEM. SAEM website. Accessed July 14, 2023.

- Musey PI, et al. Guidelines for reasonable and appropriate care in the emergency department (GRACE): Recurrent, low‐risk chest pain in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(7):718-744.

- Broder JS, et al. Guidelines for reasonable and appropriate care in the emergency department 2 (GRACE‐2): Low‐risk, recurrent abdominal pain in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2022;29(5):526-560.

- Edlow JA, et al. Guidelines for reasonable and appropriate care in the emergency department 3 (GRACE‐3): Acute dizziness and vertigo in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2023;30(5):442-486.

- Westafer, L. New guidelines aim to help the evaluation of chest pain. ACEP Now. 2021;40(9):17.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Gradually Circling Around the GRACE Project’s “Reasonable Practice””