Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 06 – June 2014

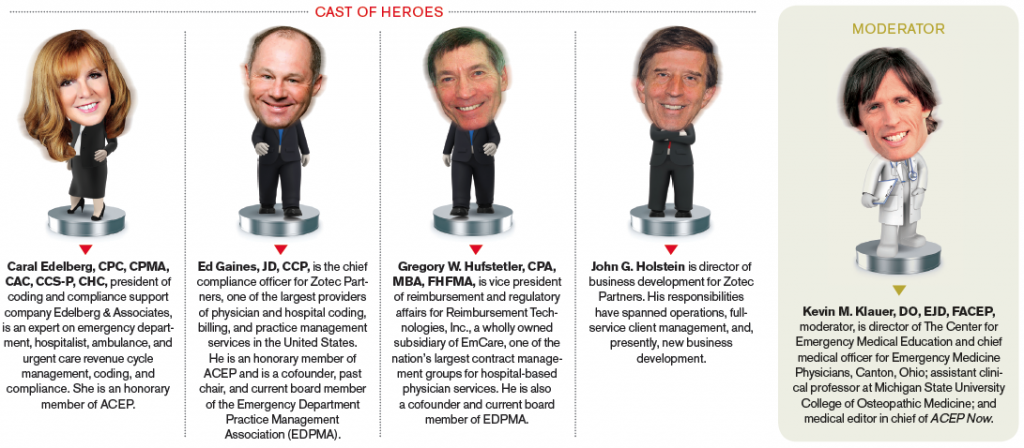

Kevin M. Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP: What are top challenges in 2014 for health care? Where do we see health care going in 2014? What do you see as non-physicians and executive leaders in emergency medicine?

Ed Gaines, JD, CCP: I think the single biggest challenge we have in health care overall, and specific to emergency medicine, is this “Greatest of Three” formula (GOT) and interim final rules that we have under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations. What the commercial health plans are doing, in essence, is using those interim final rules to drive out-of-network (OON) reimbursement to approximately 125 percent of Medicare. Greg Hufstetler has analyzed the EmCare data and found that three of the major health plans—Aetna, Cigna, and UnitedHealthcare— have shifted more then $600 million from the plans to the patients in 2013 using the GOT formula. It really ties to a theme that our CEO and founder Scott Law has talked about. He calls it the great fleecing of the American patient. The plans are paying Medicare plus 20 to 30 percent of the charge, which leaves a significant “balance bill” due from the patient. The balance of the provider charges less the unreasonably low reimbursement by the health plans is being transferred to the patient, and the patient’s having to pay that in states where there isn’t a restriction on balance billing, and that’s a real problem for emergency medicine and all hospital-based specialties. So if we look out over the next five to 10 years, can the emergency medicine specialty exist on a Medicaid- or Medicare-style reimbursement methodology? I don’t think it can exist in the way it does today with independent ED group practices. The recently published Health Affairs study showed reimbursements set to Medicare and Medicaid would produce double-digit losses for most EDs and that historically privately insured patients have subsidized all other ED payer classes.1 With the states that do not have Medicaid expansion, there’s simply not enough reimbursement in the system to pay for the moral imperative, the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA) imperative, and the imperative of emergency medicine to care for all comers to the ED. I think that’s the single biggest challenge we have in EM.

Gregory W. Hufstetler, CPA, MBA, FHFMA: I’d say adapting to all of the changes brought about by the ACA would be the generic answer. My number-one concern would be the prevalence of the high-deductible health plans (HDHP) being offered through the exchanges. What you really see is simply a new form of self-pay when you have $2,000 and $3,000 deductibles and higher, shifting patients from uninsured to the high-deductible plan. A second concern would be the morphing of the Physician Quality Reporting System into a penalty phase in the next couple of years coupled with the arrival of value-based purchasing modifier systems, which arise out of the ACA. Those two things, in combination, bring exceptional complexity, and when you see the flow chart of those two things together, it introduces almost a sense of despair and skepticism to the house of medicine. In terms of early arrivals, the GOT in 2013, this past calendar year, has resulted in major national commercial payers systematically lowering their non-par reimbursements and justifying it from the GOT regulation. Of course, two of those three rates in the GOT criteria are set by the payers and are thus in a black box unknown by providers. So payers have realized, and their legal counsel has sanctioned the systematic ratcheting downward of these payments, and that poses serious challenges this year and beyond.

Caral Edelberg, CPC, CPMA, CAC, CCS-P, CHC: One of the things that I think we are all still reeling from is this ICD-10 schizophrenia. We had physician groups gearing up for it and hospitals paying millions of dollars to get ready for all of the big change that didn’t happen. So do we continue to prepare for it? Do we wait until the last minute and see if we want to spend some more money keeping people’s skills sharp and then take a chance it’s going to get put on the back burner again?

Additionally, somehow the patients have become customers, and with them as customers, the hospitals are driven to assure top levels of patient satisfaction. You have your door-to-doctor time; you have your patient comments about the care they’re receiving. Many times, none of that has to do with the quality of medical care that’s being provided, and I think we’ve seen physicians who take a little bit more time with their patients and are a little bit slower than everyone else get called to the carpet for that. I see that happening more and more as we talk to more groups across the country. Patients have been given more power, but I’m not sure they’ve been educated on how to use it, and that concerns me a lot.

I see so many changes with so many of the payers. Many of them have now set up their own internal audit departments to audit our claims and track whether our charges go up the slightest little bit or if one physician is charging higher than another. Sometimes they don’t really care about the reasons; they just want to bust your chops about it, and we have to defend ourselves. I see that more and more groups are spending more and more money on nonclinical care just to stay ahead of the audits and stay ahead of the impact of electronic medical records (EMRs) and their documentation issues. So, what I see is money tightening up and nonclinical expenses very necessarily going through the roof.

I can see the ED of the future having more to do than provide ED care. …I can see our role changing, and if we’re indeed going to be responsible for that and accountable for these outcomes, we’re going to need a lot more influence…

–Caral Edelberg, CPC, CPMA, CAC, CCS-P, CHC

KK: Those are great follow-up comments, and I have to apologize: when you’re not going first, it leaves you a little less to say, but you’ve found some great things to add to the conversation. So, John, what do you think?

John G. Holstein: There are a couple of things I always like to include in the top health care challenges in general: one being the development of health information exchanges and the second being heath care going mobile or health care going retail. Shifting to the top emergency medicine issues, I really believe there are three of them, one of which is defining emergency medicine’s role and function in the care continuum. The second one is emergency medicine self-defining the value metrics by which it will be measured, and the third challenge is the specialty has to really assess and address some macro issues that I truly believe are directly impinging upon two core issues, namely EMTALA and the prudent layperson definition of an emergency. These issues are the infusion of the newly insured; the urgent care explosion; the high-deductible plans, as my three colleagues have mentioned; hospitals going into the insurance business; and what I would call the “retailization” of health care. When patients can self-direct getting their own lab tests today, the landscape has truly changed. I believe these landscape changes are going right at the heart of core issues of the specialty.

KK: I think those are huge, and I appreciate the segue into the specific challenges for emergency medicine. Let’s reverse the order here on the challenges specific to EM. Caral, what do you think? Any particular challenges you see that are unique to emergency medicine that haven’t been mentioned already or that are more global to health care in general but something specific to emergency medicine?

CE: I think we’re still the front door to much of the health care that is provided, but what happens on the other side of that door has been significantly redefined and will continue to be redefined. We have Walgreens and Walmart now providing urgent care, and patients don’t quite know where they fit and where they’re supposed to go. I think that’s going to be a huge challenge for emergency departments. The hospitals are pushing the emergency physicians to get into some involvement with urgent care, some involvement with hospital medicine, some involvement with Walgreens and Walmart type urgent care to assure quality in their areas, to try to compete with them, and our physicians are doing a lot more than seeing patients.

GH: I think simply getting the message out about the unique payer mix and payment stream for emergency medicine is a major and vital challenge. I’ve developed a suite of tools or talking points for advocates within our organization and even utilized it to some degree within our trade association. I liken the emergency department group to swimmers in a very turbulent ocean, and that’s because fully 50 percent or more, often 60 to 70 percent, of the patients who arrive are either low pay, that is Medicaid, or no pay, that is uninsured. The average would be 20 percent uninsured and 30 percent Medicaid. Now, what other business has 50 to 60 percent of its customers in a status of no pay or low pay and whose revenues fund about one-third of the cost to deploy the service? None.

So what are the lifelines for this swimmer who’s in very turbulent waters indeed? Well, there are two lifelines: the one is fair commercial payments—that is, from the Blues and from the other national payers, such as Aetna, Cigna, United—and the second would be a hospital subsidy. A lifeline is necessary whenever there is inadequate and unfair payment from the commercials to offset the losses from the uninsured and Medicaid, and what you see now with the “Greatest of Three” taking shape is a massive shift back to the very patient who is unable or unwilling to pay. The question is: will the hospitals now be able to step up and increase their subsidies—or, in some cases, start subsidies for the first time—in order to strengthen the one remaining lifeline keeping the emergency group intact? Of course, I don’t know for sure, but I am worried about the fiscal health of many of our hospital partners in an age in which disproportionate share support has been scaled back massively and value-based measures will result in steep penalties to hospitals.

KK: Ed, do you want to comment about 2014?

EG: We frequently hear from Medicaid agencies that the way they’re going to reform Medicaid, or a principle way they’re going to reform Medicaid, is to keep people out of the emergency department, and we’ve seen those attempts despite the EMTALA mandate. We’ve seen that in Washington state initially with their very restrictive diagnosis and ED visit limitations. We’ve seen expanded cost sharing (eg, coinsurance) for non-emergency use of the ED in what I call the “Arkansas Model” of Medicaid expansion. This premium support model has been picked up by Pennsylvania, Iowa and several other states seeking to use federal matching funds to purchase Medicaid health plan policies for the working poor. In North Carolina, Medicaid is looking at Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) to drive significant percentages of patients out of the ED. Yet the Oregon Medicaid expansion study showed that when Medicaid expanded in Portland, ED utilization went up approximately 40 percent. It highlights the challenges we have of the moral and legal imperative of the EMTALA mandate and the issues surrounding the chronic conditions, which you know much better than all of us, in terms of that Medicaid patient base and how we deal with it. How do we arm the state chapters to be able to go and make the case that reforming Medicaid on the backs of emergency physicians is not the answer? Maybe 20 years ago, we heard, “Stand behind EMTALA and prudent layperson, and don’t engage in the conversation.” I don’t hear that much anymore—emergency physicians want to be at the table. As Dr. Lynn Massingale of TeamHealth has said for years, “We’re either at the table or on the table,” and that is very hopeful for the future that the level of engagement of ED physicians has really changed for the better.

KK: Something you mentioned the readers might want to hear more about: you noted cost-sharing models that are out there. Is there anything you would like to expand upon beyond just high-deductible plans shifting burden to the patient?

EG: You know the ACO, the shared savings models, and the bundled payment experiments that were done in what was called the ACE demonstration, which is now the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative on the Medicare side. I think both of those types of programs appear from a 40,000-foot perspective as an attempt to move away from fee-for-service to something else. The question is: how do you move chronic care and patients with multiple comorbidities into a bundled payment? Maybe a bundled payment works great on hips and knees or coronary artery bypass grafting, but is it really going to affect how Dr. Klauer is going to work up the nursing home patient who is weak and dizzy, has several chronic conditions like congestive heart failure, and does not know why he doesn’t feel good? How much is his ordering or diagnostic treatment protocol going to impact the total bundle payment at the end of the day? I think the good news for us is nobody’s totally figured out emergency medicine yet from an ACO or bundled payment perspective—we’re in the very early innings. We’re the X factor. When you listen to officials of leading hospitals who have experimented with bundled payment and ACOs talk about bundled payment arrangements or ACOs, they scratch their heads and say, “Well, but we had to carve out emergency medicine.”

KK: When they can’t figure us out, we have two ways to look at it. It does provide great opportunity for us to shape their understanding and create, perhaps, a larger scope for emergency medicine. But if they don’t understand EM, they might also interpret this in another direction, as many have already done: that the emergency department is an expensive place to receive care and people shouldn’t go there, clearly a preposterous assumption about our specialty.

EG: But one of the biggest challenges we have, Kevin, is the old pit-doctor mentality from 20 years ago that I do not want to understand how these changes may impact my practice and my livelihood, that I’m going to work my shift, I’m going to go home, I’m going to take care of my family, I’m going to educate my kids and whatever, and I’m not going to get involved. The biggest threat is that’s a doctor who thinks all of this stuff is a lot of white noise and somebody else is going to do it for him or her. We all can make a difference, and we should consider how we all stand on the shoulders of the giants of emergency medicine who carved this specialty out of solid rock—they all stepped up time and time again, and we all need to follow their leadership and example.

KK: We’re going to do it collectively and collaboratively, but we all have to be involved; at the least, we have to be informed. Do you remember that book from several years ago, Who Moved My Cheese? Well, they’re moving our cheese. We have to evolve and move with it. If we don’t change the way we think and the way we practice, this specialty will be at real risk. I have a question for each of you, based on a comment that Ed made about utilization. How many tests does it take to diagnose a hip fracture? Most emergency physicians when they initially respond will say one: a hip X-ray. How does that look to CMS and third-party payers? How many tests and how many dollars does it take to diagnose a hip fracture? Well, it’s the cost of a hip X-ray, an IV, a PT, PPT, an INR, a CBC, a BMP, type and screen, a urinalysis, maybe a Foley catheter, a chest X-ray, an ECG, and anything else the admitting physician may want for medical clearance. It appears when they take care of a hip fracture payment mainly from medical clearance, the cardiologist and anesthesiologist spend no money except for their consultation. They are so efficient. But for the emergency physician, it takes a whole lot more to diagnose a hip fracture when you look at all the tests we order.

EG: What you’ve raised is a huge issue, I believe, because when you talk to docs about what the expectation is of those specialists, the specialists will literally not come in and treat the patient until all of what you’ve described has been done in advance. It’s the expectation of your specialist, who is essentially demanding that you should do all this additional service. That messaging about who is driving the utilization of advanced imaging, for example, is not being made in my opinion, but it is going to be critical when it comes to bundled payments, ACO, different payment arrangements versus fee-for-service. Now, all of a sudden, maybe my client is in a gain-sharing deal and costs per patient are a factor, so she’s viewed as high cost but at baseline quality. Then her gain-sharing group’s going to look at me and say, “Hey, what’s your problem? You seem to be working up these patients very extensively,” but that’s what the specialists are expecting. Changing the specialists’ expectations for those comprehensive workups could be a major practice challenge with these new payment models.

KK: Those are great comments. I’ll throw in, for the readers and emergency physicians out there who may not be aware of how the value-based modifier for the physician fee schedule is rolling out, that 50 percent of value-based modifier calculation is about cost and utilization. We just don’t have a very good idea yet how they’re going to calculate cost and utilization. It seems clear to me that if we’re spending dollars that really should be spent by other providers, we’re accepting financial responsibility for things we don’t need, and that’s a problem.

GH: I think fundamentally the discussion about cost is a very important one—that is, keeping cost in the ongoing discussions about value. Cost accounting is an old discipline, but it’s one that’s missing, if not lost, in emergency medicine. I believe it needs to be front and center. I’m not talking charges but actual cost so that we can argue the value of emergency medicine. I think that if you were to match an hour’s worth of fully loaded cost to an hour’s worth of net revenue, the average legislator and regulator would be very surprised to see how close the margins are in the large majority of EDs.

KK: That’s a great perspective. I hadn’t thought about it that way. I really like the way you think on that, Greg. Caral, any additional thoughts on that?

CE: I see our specialty changing. I don’t want to use the word “gatekeeper” because it has such a negative connotation for so many health care professionals, but it’s a role I think we’re going to end up playing. We’re going to be directing more than just the emergency care. I can see the emergency department of the future having more to do than provide emergency department care. I can see us essentially responsible for driving front-end cost for health care, which is everything up to, and possibly including, the admission or everything up to the consultant coming in. I can see our role changing, and if we’re indeed going to be responsible for that and accountable for these outcomes, we’re going to need a lot more influence and a lot more power over what happens to the patients we’re responsible for.

KK: That is a great perspective, and that actually leads me to my next question. I’m going to ask you all just for one line about whether you think the scope of practice in emergency medicine will be shrinking or expanding in the next couple of years.

EG: Expanding

CE: I agree absolutely.

JH: Yes, I would see it expanding to more alliances with hospitalists, potentially radiologists and anesthesiologists.

GH: I agree entirely with John’s sentiment.

KK: Do you think these current times [health care reform] in emergency medicine are more critical than previous eras?

EG: Yes, most critical.

JH: Yes, this is another Wiegenstein moment.

GH: Yes, totally agree, most critical.

CE: I can’t say that it is, but I need to qualify that. It’s been close to 40 years that I’ve been involved in emergency medicine, and every big change that we’ve seen was a challenge for us because, at that point, we didn’t have the tools, expertise, or organization to manage it. And from that, we grew ACEP, we grew EDPMA, we grew some amazing talent within our specialty. I see this as just another opportunity for us to learn more about what needs to happen in our specialty, another opportunity for people who want to step up and take a greater role and who have opinions and new ideas to put them into play.

KK: Could you briefly state what your role is, and how your role impacts emergency medicine?

EG: My role I really see as an advocate for emergency medicine and a facilitator. When Greg and I cofounded EDPMA with others more than 15 years ago, we looked at what we were doing to support the specialty, and obviously we couldn’t be members of ACEP because we weren’t physicians. We needed a trade umbrella to represent the various interested stakeholders to go to Washington and go to the state capitals, and it became the vehicle for us to be able to channel all of our energies. It was started in a crisis, the Medicare reassignment crisis, and then we had prudent layperson and Medicaid restrictive diagnosis and triage fee crises hit us right afterwards in the late ’90s. We’ve helped emergency medicine because, as one of our colleagues said, when we come together in EDPMA, “we take off our respective company uniforms and focus on the greater good and on achieving results.” It’s rewarding on many levels because we have been fortunate to be part of something larger than each of our companies or ourselves. The association also facilitated our partnership with ACEP and other EM stakeholders. It’s been a fantastic working relationship, and I believe we have made a difference because we cared and we worked together.

JH: I consider it my duty, my responsibility, to be a practice management expert and resource to emergency physicians so their practices will be financially successful. I have additionally always considered it a privilege to be an advocate for the specialty, be it in print, presentations, or payer negotiations. The bottom line is for us to absorb the business aspects of the specialty so the physicians can do what they went to medical school to do, and that is to take care of patients.

GH: I simply am the quarterback of an amazing team of 50-plus people in one of the nation’s largest emergency medicine staffing companies, a subsidiary that does the billing and the back-office business operations with talented directors, managers, and staff. It’s really my job to take the burden of all that nonclinical demand for success off of the clinicians’ shoulders and to create and implement high-performing solutions in the areas of information technology, government compliance, third-party audits, third-party enrollment, coding, billing, cash collection, manage care negotiations, and fee schedule maintenance.

CE: I feel like I have to keep reinventing myself. I own a very large technology coding and compliance company. In order to do that and represent what we do to support our clients, which are hospitals, physicians, and payers and a little bit more of everything, I’ve never been able to step away from the sense that I have to know the details. I feel like in order to represent the priorities and potential solutions to our physicians and our clients, I really have to understand the issues, which keep changing all the time. I always feel like I have to be down in the weeds on things in order to understand them well enough to provide the right kind of consultation, the right kind of advice to our docs.

No Responses to “Health Care Professionals Share Insights on Challenges, Future of Emergency Medicine”