Editors’ Note: This article was accepted on May 2, 2020, and was accurate at that time. Because information about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 is evolving rapidly, please verify these recommendations and information.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 06 – June 2020As we come to grips with the COVID-19 pandemic and how it’s changed how we practice, it’s important to employ optimum strategies for staff and patient flow. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, however, because the coronavirus has impacted states and municipalities in vastly different ways.1 The disease’s prevalence, hospital and resource capacity, and testing capabilities result in different problems and solutions. However, several core concepts can help each emergency department and its leaders determine new strategies for practicing post COVID-19.

With the extreme contagion factor inherent in the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulty identifying infectious individuals, it is clear that ED arrivals need sophisticated sorting. The carrier capacity of young asymptomatic individuals must also be considered. The ED intake process must identify those who are most likely infected and protect vulnerable populations from the virus. We must design patient segmentation that will cohort patients in a meaningful way while being resource-wise and efficient.

It is well-accepted that patient segmentation and streaming, which includes placing patients in acuity-based cohorts, is considered a best practice.2–6 Currently, most emergency departments have different geographical zones, such as a fast track for minor complaints. A growing number of departments are implementing a mid track for middle-acuity patients. These patients can be treated in a vertical flow model in lounge chairs, saving the most precious real estate (patient beds) for those with the greatest needs.

With the extreme contagion factor inherent in the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulty identifying infectious individuals, it is clear that ED arrivals need sophisticated sorting.

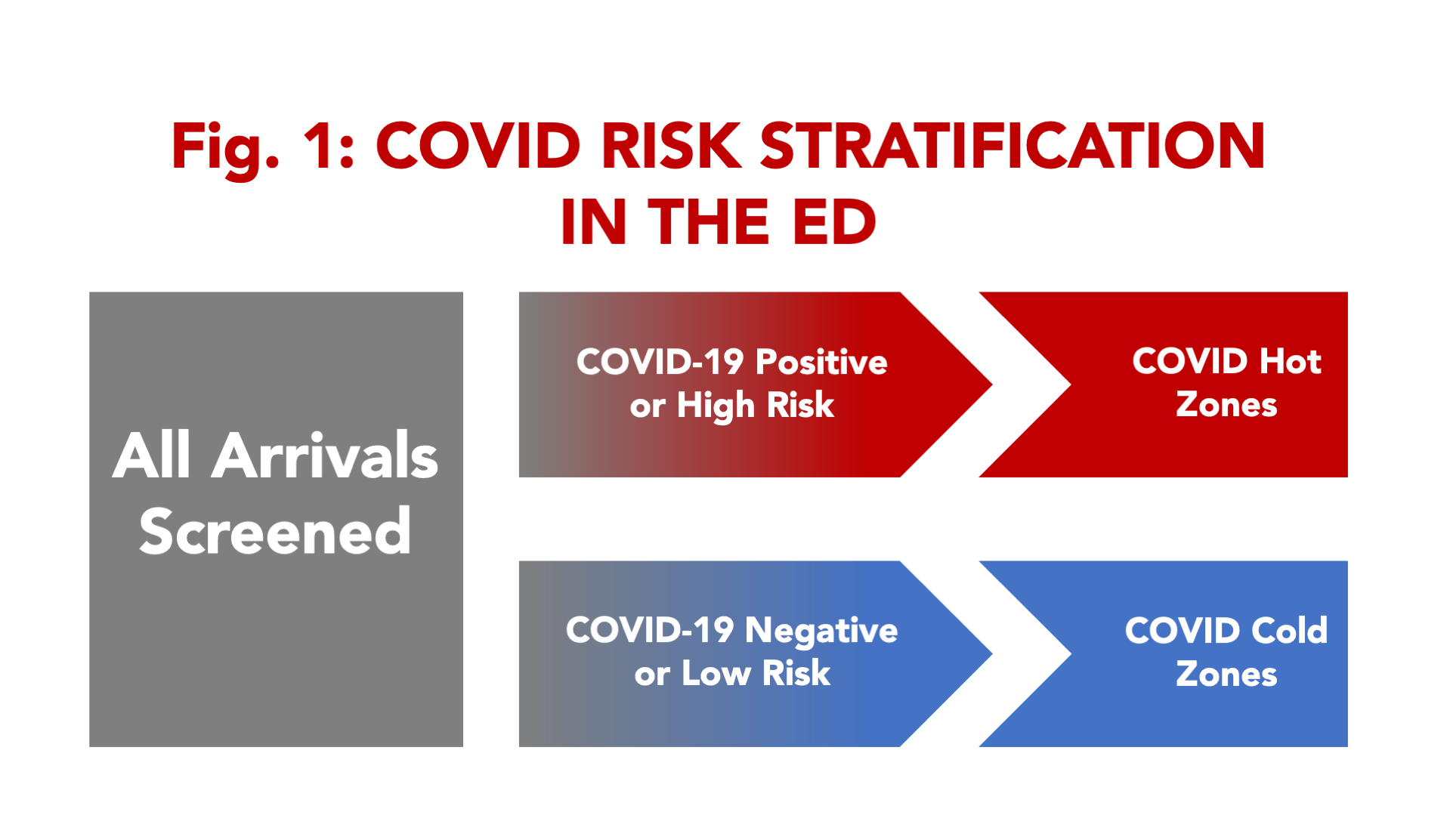

But even more sophisticated patient flow models may be required due to the pandemic. Because asymptomatic people may transmit the disease to others, some emergency departments have already developed processes for universal screening (see Figure 1).

For example, screening staff need to wear the highest-level personal protective equipment (PPE) and be skilled at differentiating arriving individuals into the workflow. In many hospitals, the emergency department has become the universal point of entry. Patients, staff, and others arriving with essentially no risk are screened for their purpose for entering. Until universal rapid point-of-care testing is available, a screening procedure is employed. Initial sorting can begin by eliciting symptoms, taking a surface temperature, and fielding high-risk queries. A history of exposure two to 14 days prior with subsequent fever, cough, shortness of breath, and/or loss of taste and smell correlate with COVID-19 positivity.7 Screening is also used to identify high-risk patients who should be protected from COVID risk:

For example, screening staff need to wear the highest-level personal protective equipment (PPE) and be skilled at differentiating arriving individuals into the workflow. In many hospitals, the emergency department has become the universal point of entry. Patients, staff, and others arriving with essentially no risk are screened for their purpose for entering. Until universal rapid point-of-care testing is available, a screening procedure is employed. Initial sorting can begin by eliciting symptoms, taking a surface temperature, and fielding high-risk queries. A history of exposure two to 14 days prior with subsequent fever, cough, shortness of breath, and/or loss of taste and smell correlate with COVID-19 positivity.7 Screening is also used to identify high-risk patients who should be protected from COVID risk:

- >65 years

- Nursing home or long-term care facility residents

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma

- Immunocompromised

- Body mass index >40

- Diabetes, renal disease, liver disease, or dialysis

The process will need to segregate those patients into COVID hot and cold areas. Where there is little risk of COVID-19 disease, staff are outfitted in lower-level protection and manage patients using more traditional patient flows and workflows (see Figure 2).

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Help Prevent Coronavirus Spread by Reevaluating ED Flow”