Editors’ Note: This article was accepted on May 2, 2020, and was accurate at that time. Because information about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 is evolving rapidly, please verify these recommendations and information.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 06 – June 2020As we come to grips with the COVID-19 pandemic and how it’s changed how we practice, it’s important to employ optimum strategies for staff and patient flow. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, however, because the coronavirus has impacted states and municipalities in vastly different ways.1 The disease’s prevalence, hospital and resource capacity, and testing capabilities result in different problems and solutions. However, several core concepts can help each emergency department and its leaders determine new strategies for practicing post COVID-19.

With the extreme contagion factor inherent in the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulty identifying infectious individuals, it is clear that ED arrivals need sophisticated sorting. The carrier capacity of young asymptomatic individuals must also be considered. The ED intake process must identify those who are most likely infected and protect vulnerable populations from the virus. We must design patient segmentation that will cohort patients in a meaningful way while being resource-wise and efficient.

It is well-accepted that patient segmentation and streaming, which includes placing patients in acuity-based cohorts, is considered a best practice.2–6 Currently, most emergency departments have different geographical zones, such as a fast track for minor complaints. A growing number of departments are implementing a mid track for middle-acuity patients. These patients can be treated in a vertical flow model in lounge chairs, saving the most precious real estate (patient beds) for those with the greatest needs.

With the extreme contagion factor inherent in the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulty identifying infectious individuals, it is clear that ED arrivals need sophisticated sorting.

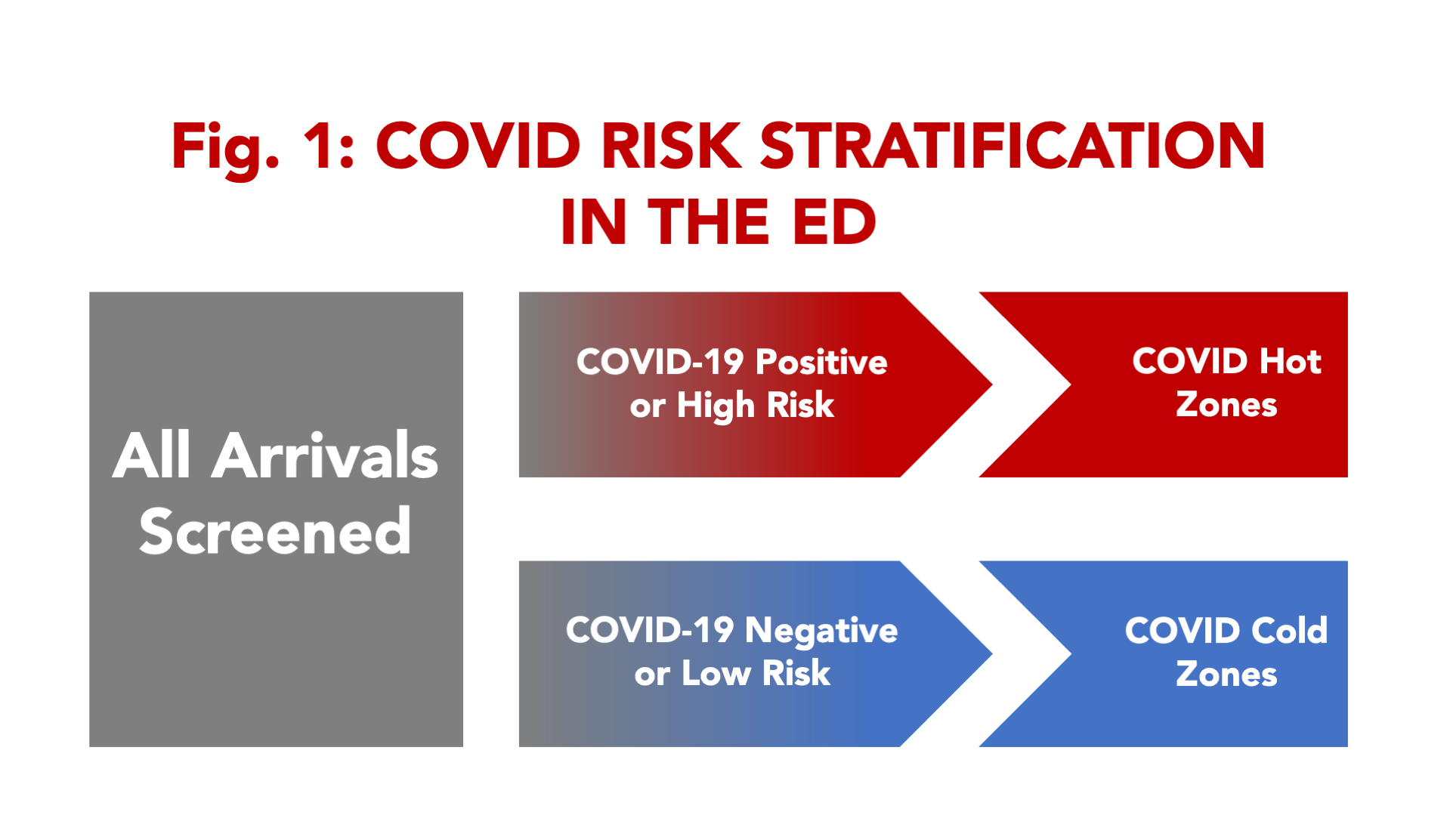

But even more sophisticated patient flow models may be required due to the pandemic. Because asymptomatic people may transmit the disease to others, some emergency departments have already developed processes for universal screening (see Figure 1).

For example, screening staff need to wear the highest-level personal protective equipment (PPE) and be skilled at differentiating arriving individuals into the workflow. In many hospitals, the emergency department has become the universal point of entry. Patients, staff, and others arriving with essentially no risk are screened for their purpose for entering. Until universal rapid point-of-care testing is available, a screening procedure is employed. Initial sorting can begin by eliciting symptoms, taking a surface temperature, and fielding high-risk queries. A history of exposure two to 14 days prior with subsequent fever, cough, shortness of breath, and/or loss of taste and smell correlate with COVID-19 positivity.7 Screening is also used to identify high-risk patients who should be protected from COVID risk:

For example, screening staff need to wear the highest-level personal protective equipment (PPE) and be skilled at differentiating arriving individuals into the workflow. In many hospitals, the emergency department has become the universal point of entry. Patients, staff, and others arriving with essentially no risk are screened for their purpose for entering. Until universal rapid point-of-care testing is available, a screening procedure is employed. Initial sorting can begin by eliciting symptoms, taking a surface temperature, and fielding high-risk queries. A history of exposure two to 14 days prior with subsequent fever, cough, shortness of breath, and/or loss of taste and smell correlate with COVID-19 positivity.7 Screening is also used to identify high-risk patients who should be protected from COVID risk:

- >65 years

- Nursing home or long-term care facility residents

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma

- Immunocompromised

- Body mass index >40

- Diabetes, renal disease, liver disease, or dialysis

The process will need to segregate those patients into COVID hot and cold areas. Where there is little risk of COVID-19 disease, staff are outfitted in lower-level protection and manage patients using more traditional patient flows and workflows (see Figure 2).

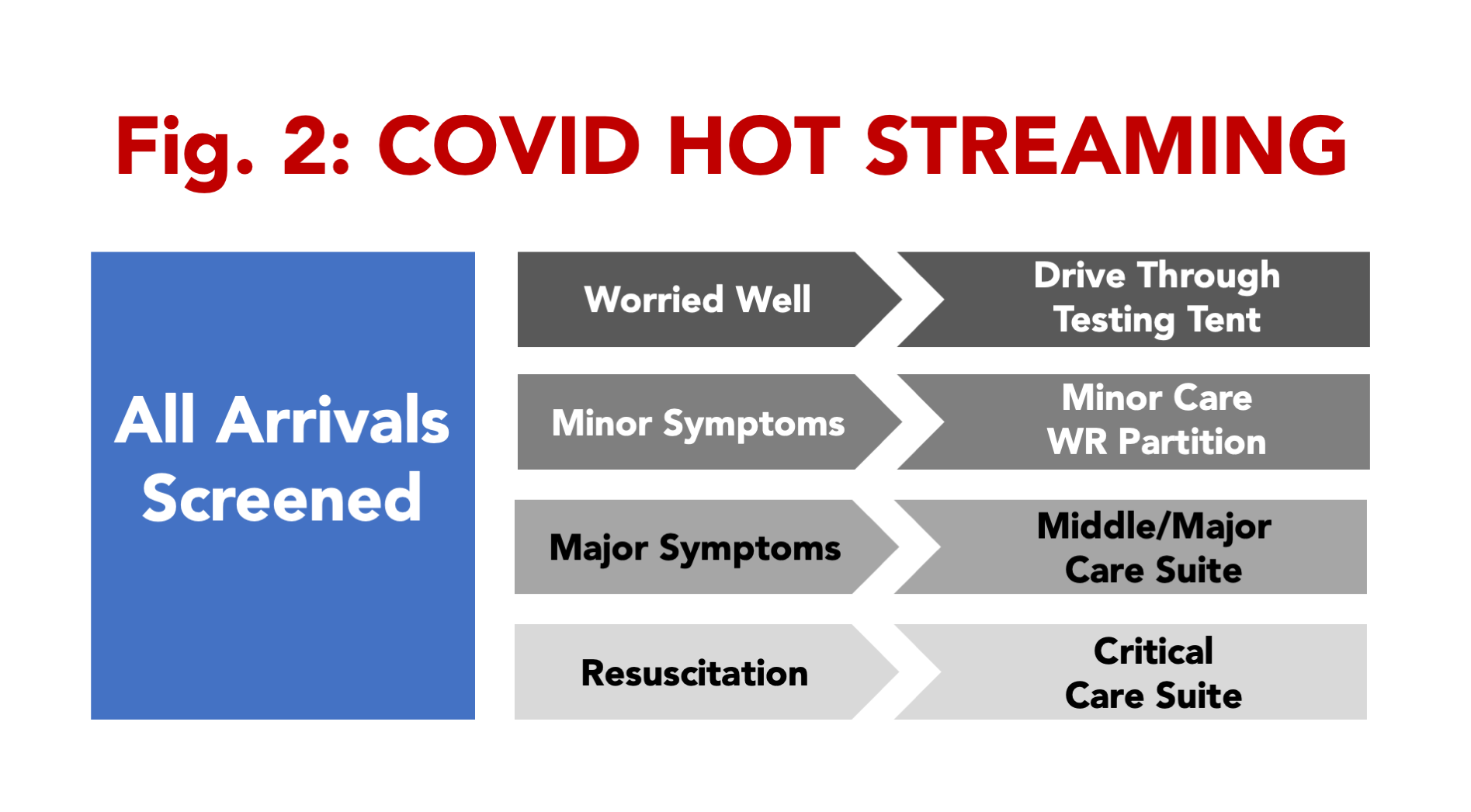

Smaller emergency departments, or those with lower disease prevalence, might only have a small number of spaces for COVID-19 patients and one room designated for COVID critical care.

High-priority (eg, trauma, stroke, burn, or obstetric patients) and high-risk patients need to move through the screening process quickly and be transported to appropriate critical care areas. Resuscitation areas in COVID hot zones need to process all critically ill COVID-19 patients and any arriving patients with an unknown status. Patients are treated by staff in full PPE, including N95 masks or powered air-purifying respirator, eye shields, gowns, and gloves, who use strict donning and doffing procedures.8

Wearing PPE presents notable challenges. In addition to it being time-consuming to suit up, frontline workers report extreme difficulty in tolerating the warmth of PPE and most can’t withstand full protection from SARS-CoV-2 for more than four hours.

Another strategy includes not allowing staff to float back and forth between hot and cold zones, which exposes patients and staff members to the risk of infection. This will decrease staffing flexibility and impact staffing and workflow on the front lines.

A busy emergency department with higher volume that is part of the epicenter may be able to populate and staff a separate zone for middle- and higher-acuity noncritical patients who need testing and treatments. This will take place in a designated ED care space and may include a lounge chair area. The institution will have to decide whether to take infected patients into imaging suites. Radiology staff will have to provide guidance on appropriate use of plain imaging and high-level scans.

In some cases, having PPE-protected imaging staff take portable films and using plastic-covered portable units is more efficient than cleaning an imaging room between patients. This is even more important in scanning suites, where disinfecting scanners and gantries may take more than an hour. Ultrasound procedures are typically done bedside with disposable sheaths and PPE-protected staff. Health care workers in these areas should wear basic PPE including a surgical mask, eye shield, gown, and gloves.9

Other arriving patients will have risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection but may have low-acuity medical needs and little indication for diagnostic testing. These patients may be best served by evaluation and disposition directly from the intake or screening area. In many emergency departments that have forbidden visitors, the waiting room may serve as a convenient area for minor care.

Take advantage of opportunities to use outdoor spaces and adjacent parking lots, with or without tents, to manage the lowest acuity needs. This includes those who simply need a screening test, those needing a “COVID clearance” to return to work, and the “worried well.” Where drive-through operations can be developed, low-acuity patients could remain in their cars, with self-collected specimens evaluated in a timely manner.

Procedures for patients who are best-served with medication nebulizers are most safely done outdoors, downwind of any building entrances and away from ED staff. This may require placing chairs in a weather-protected area, with an outlet for compressed air or medical oxygen to power the nebulizers.

Also consider if patients can be screened and managed virtually without provider contact. Virtual encounters and telemedicine opportunities are gaining popularity in emergency medicine.10

Remember, once providers have had contact with COVID-19 patients, they could infect other personnel and contaminate equipment including computers, phones, machines, and so forth. This supports the argument to use virtual care as much as possible and have medical scribes assist physicians. By doing this, the same people touching infected or high-risk patients as part of diagnostic or therapeutic care will not need to touch equipment.

We would be remiss to not include a word about “direct care” and “indirect care” of COVID-19 patients. Where PPE is being conserved, hospitals may employ a strategy to carefully segregate workers who contact patients directly from workers who do not. Using scribes in the emergency department lends itself to this workflow segregation.

COVID-19’s impact on ED volumes and acuity has been stunning. According to the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance, most of the more than 1,200 ED members sharing data have actually seen ED volume go down 40 percent since mid-March because patients have avoided the emergency department due to infection risk.11,12

Acuity breakdown and admission rates are changing at some locations. Most do not think that the 40 percent drop will be maintained into summer because American emergency departments are the source for unscheduled health care and that demand will continue. This means ED leaders will need to consider staff and patient flow in their emergency departments from scratch and be informed by the data. The data can suggest the zones or service lines needed, their hours of operation, how many beds are designated, and how each area should be staffed.

Now more than ever, it is all about flow.

References

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Cases, Data, Surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/index.html. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- van der Linden C, Lindeboom R, van der Linden N, et al. Managing patient flow with triage streaming to identify patients for Dutch emergency nurse practitioners. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20(2):52-57.

- Aksel G, Bildik F, Demircan A, et al. Effects of fast-track in a university emergency department through the National Emergency Department Overcrowding Study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64(7):791-797.

- Hwang CE, Lipman GS, Kane M. Effect of an emergency department fast track on Press-Ganey patient satisfaction scores. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(1):34-38.

- Arya R, Wei G, McCoy JV, et al. Decreasing length of stay in the emergency department with a split Emergency Severity Index 3 Patient Flow Model. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(11):1171-1179.

- Soremekun OA, Shofer FS, Grasso D, et al. The effect of an emergency department dedicated midtrack on patient flow. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):434-439.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Infection Control Guidance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Optimize PPE Supply. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/index.html. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- Izzo JA, Watson J, Bhat R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid telemedicine encounter in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(11):2061-2063.

- About Us. Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance website. Available at: https://www.edbenchmarking.org/about-us. Accessed May 21, 2020.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Help Prevent Coronavirus Spread by Reevaluating ED Flow”