The Case

A 3-year-old boy with watery diarrhea for the past three days as well as vomiting and fever that started the day prior is brought to the emergency department by his mother. No recent traveling or antibiotic usage is reported. He has otherwise been in good health. On physical exam, the patient appears well-developed, nourished, alert, and oriented. The vitals are stable, and the abdomen is non-tender and non-distended. At shift change, the patient’s condition seems to be improving. He can tolerate apple juice and no longer has fever. The patient is signed out to the incoming physician with pending diagnostic studies.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 07 – July 2017

Figure 1: Abdominal X-ray showing increased bowel gas.

PHOTO: Nick Kwan

However, the patient starts to develop tarry black stools shortly after shift change, and on reassessment, the patient’s blood pressure is 80/45. He appears to be pale with a rapidly deteriorating clinical status. The initial diagnostic studies are significant for hematuria, metabolic acidosis with elevated creatinine, and C-reactive protein. Abdominal X-ray shows increased bowel gas (see Figure 1), and abdominal ultrasound does not suggest any radiographic evidence of intussusception. Two hours after shift change, the patient becomes more hypotensive, and his abdomen becomes more rigid. Emergent critical care transport is initiated while the patient is placed on vasopressors to maintain a systolic blood pressure above 90. The patient is transported to a tertiary pediatric facility, where his stool culture was positive for Escherichia coli 0157, the most common cause of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) in the United States. Fortunately, the patient is diagnosed, treated for HUS, and makes a full recovery.

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of recognizing the symptoms of HUS. HUS is a serious complication resulting from E. coli infection, most often with Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC). The toxins produced by STEC activate the endothelium, create a prothrombotic state, and lead to inflammation. E. coli 0157 is the most common strain of STEC in the United States and accounts for more than 90 percent of HUS cases in children under 5 years of age. About 5 percent to 15 percent of people infected with STEC develop HUS. The incidence is about 2–3 per 100,000 children under 5 years of age in the United States.1,2 HUS can have severe complications, and early recognition and treatment are paramount to preventing morbidity and mortality.

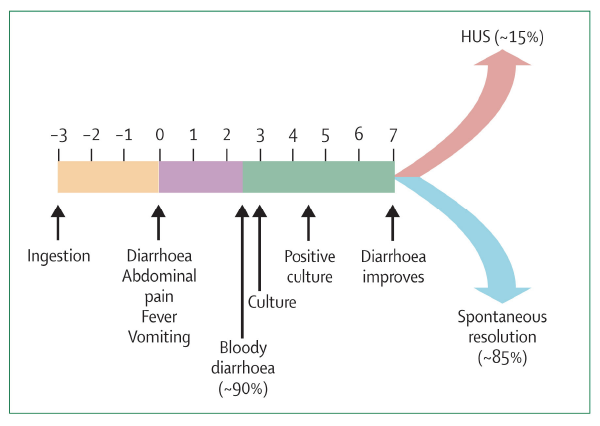

Figure 2: Progression of E. coli 0157 infection in children.

GRAphic: Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1073-1086.

The clinical course of HUS is shown in Figure 2. Diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and vomiting develop a few days after inoculation with the pathogen. Within a week, the patient’s condition can either resolve or develop to full-blown HUS. HUS is defined by the classic triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal injury. Though the long-term prognosis for renal recovery is good, up to 50 percent of patients with HUS may require dialysis during the acute phase. Additionally, HUS can affect many other organ systems, including the central nervous system (CNS), gastrointestinal tract, liver, pancreas, and heart. CNS involvement, including seizures, coma, and stroke, is seen in up to 20 percent of cases and is associated with increased mortality.3 In this case, the patient was colonized with E. coli 0157 and had hematuria, rectal bleeding, hypotension due to significant fluid loss, and early renal injury. Early recognition and treatment resulted in a complete recovery.

Dr. Kwan is an emergency physician with Emergency Medical Management Associates and associate medical director at Garfield Medical Center in Monterey Park, California.

Dr. Kwan is an emergency physician with Emergency Medical Management Associates and associate medical director at Garfield Medical Center in Monterey Park, California.

Ms. Kwan is a MS2 at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Ms. Kwan is a MS2 at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

References

- Mayer CL, Leibowitz CS, Kurosawa S, et al. Shiga toxins and the pathophysiology of hemolytic uremic syndrome in humans and animals. Toxins (Basel). 2012;4(11):1261-1287.

- Noris M, Remuzzi G. Hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(4):1035.

- Nathanson S, Kwon T, Elmaleh M, et al. Acute neurological involvement in diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(7):1218-1228.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Is Rare but Serious Complication of E. Coli Infection”

August 13, 2017

lewis d. friedlander mdNeed more discussion about management and in particular large volume fluid resuscitation prior to or at the same time as pressors. Other points would be differential diagnosis and work up as well as evaluations of other serious gastroenteritis syndromes with diarrhea and hypotension

May 22, 2021

Andrew Kennedy MDNice reminder of rare complications of a common presentation. Thanks.