Instead of imaging, a clinical history and physical exam can safely evaluate back pain in ED patients with no history of major trauma

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 03 – March 2014Halfway through a busy overnight shift, the healthy 45-year-old man you are seeing for low-back pain says, “Doc, my back is killing me—the pain is shooting down my leg! Can’t you do an X-ray or CAT scan to tell me what’s wrong with me?” You took a full history and examined him thoroughly, and you don’t think imaging will reveal anything emergent, but as you consider launching into a long explanation about the risks and benefits of imaging, you hear a new ambulance arrival. You worry that after counseling he will still want imaging, and you know that your patient-satisfaction scores are monitored closely, so you order an X-ray and analgesia and decide to reassess the patient later.

As emergency physicians, we have two roles in evaluating back pain: to treat patients’ symptoms and to diagnose potentially life or limb threatening causes.

Back pain is one of the most common emergency department presenting complaints, accounting for more than 2.6 million visits in 2006.1 As emergency physicians, we have two roles in evaluating back pain: to treat patients’ symptoms and to diagnose potentially life- or limb-threatening causes. In 2006, more than 30 percent of ED patients with back pain underwent an X-ray, and nearly 10 percent underwent CT or MRI, an increase from 3.2 percent in 2002, despite the fact that imaging is not associated with improvement in clinical outcomes.1,2

A thorough clinical history and exam in patients with no history of major trauma can identify many patients for whom imaging can be avoided. Important high-risk findings (see Table 1) of bowel or bladder incontinence, significant or evolving motor and/or sensory deficit, IV drug abuse or unexplained fever, history of cancer, and advanced age (typically >70 years) are reasons to obtain imaging for low-back pain. Otherwise, imaging rarely alters management, and the emphasis should be on treatment, reassurance, and education. This is supported by guidelines from both the American College of Radiology and the American College of Physicians.3

Which patients can be safely evaluated without imaging?

- Patients with nonspecific back pain for less than six weeks and normal neurologic examination without high-risk findings can be safely discharged with reassurance and outpatient primary-care follow-up. Patients who are able to identify acute inciting event without direct trauma are much more likely to have musculoskeletal causes of back pain.

- Patients with back pain and radiculopathy corresponding to L4–L5 or L5–S1 nerve roots (90 percent of disc herniations) are also candidates for outpatient follow-up without ED imaging. A positive straight leg raise is 91 percent sensitive and crossed straight leg raise is 88 percent specific for herniated discs. Patients with signs consistent with lumbar radiculopathy should not routinely undergo MRIs in the ED. While MRI is sensitive for the disc disease, identifying herniated discs doesn’t alter ED management. One study of asymptomatic patients demonstrated that 64 percent had abnormal discs, 52 percent had bulging discs, and 31 percent had disc protrusion!4 MRI is an outpatient preoperative test for patients with persistent symptoms less than six weeks who may be candidates for spinal injections or surgery. Indications for surgery include failure of conservative therapy after four to six weeks and neurologic deficit causing disability.

- The majority of patients in both groups will improve with conservative management within four to six weeks; emergent imaging does not alter clinical outcomes.

What are the costs of different imaging modalities?

X-ray is neither sensitive nor specific to identify the etiology of acute low-back pain. It is moderately sensitive for traumatic and compression vertebral fractures. Among 20 to 50 year olds, only 1 in 2,500 X-rays leads to a clinically unsuspected diagnosis.6 The median cost of a lumbar-spine X-ray (two or three views) is $71 (range $15 to $371) based on Medicare reimbursement rates, a conservative estimate.

The next time you see a patient with back pain with no high-risk findings, spend a few minutes discussing the diagnosis and plan with the patient.

CT is a more sensitive test for vertebral fractures but is neither sensitive nor specific for spinal-cord disorders, and it has no role in the management of nonspecific back pain or patients with lumbar radiculopathy. The median cost of noncontrast lumbar-spine CT is $174 (range $34 to $1,280) based on Medicare reimbursement rates.

MRI is increasingly available in EDs nationwide, and its use has increased due to its lack of ionizing radiation and ability to image the spinal cord and nerve roots. However, it is time-intensive, limiting its applications in emergency care. In 2013, average Medicare costs for an MRI lumbar spine with and without contrast were $550 (range $166 to $2,022). MRI is the diagnostic modality of choice for patients in whom you suspect spinal-cord disorders such as cord compression, cauda equina, epidural abscess, or hematoma. For patients with a high clinical suspicion for these diagnoses, there is little utility to performing a preliminary X-ray or CT (if MRI is unavailable, you can substitute CT myelogram).

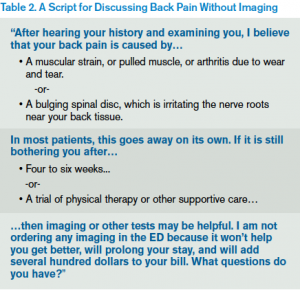

Patients may be seeking a fixable diagnosis when they request imaging, so a few minutes of education about the limited benefits and potential downsides of testing can improve both satisfaction and throughput. An example of how you might respond is shown in Table 2.

So the next time you see a patient with back pain with no high-risk findings, spend a few minutes discussing the diagnosis and plan with the patient. Reassurance and an outpatient regimen of over-the-counter analgesia and supportive care can reduce cost and length of stay—and, more important, are clinically effective.

Dr. Lin is an attending emergency physician and a fellow in the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also serves as an instructor at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Lin is an attending emergency physician and a fellow in the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also serves as an instructor at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Schuur is vice chair of quality and safety and chief of the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston. He also serves as assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Schuur is vice chair of quality and safety and chief of the Division of Health Policy Research and Translation in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston. He also serves as assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

References

- Friedman BW, Chilstrom M, Bijur PE, et al. Diagnostic testing and treatment of low back pain in United States emergency departments: a national perspective. Spine. 2010;35(24):E1406–1411.

- Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, et al. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):463–472.

- Davis PC, Wippold FJ 2nd, Brunberg JA, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria on low back pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6(6):401–7.

- Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(2):69–73.

- Borczuk P. An evidence-based approach to the evaluation and treatment of low back pain in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2013;15(7):1–23.

- Nachemson A. The lumbar spine: an orthopedic challenge. Spine. 1976;1:59-71.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “A High-Value Diagnostic Approach to Low-Back Pain”

July 1, 2015

ACR Study Finds ER Imaging for Low-Back Pain Appropriate | Advantedge Newsletter[…] Lin, MD, MPH, Michelle and Schur, MD, MHS, Jeremiah D., “A High Value Diagnostic Approach to Low-Back Pain,” ACEP Now, March 7, […]

July 2, 2015

ACR Study Finds ER Imaging for Low-Back Pain Appropriate | Emergency Medicine[…] Lin, MD, MPH, Michelle and Schur, MD, MHS, Jeremiah D., “A High Value Diagnostic Approach to Low-Back Pain,” ACEP Now, March 7, […]