Many emergency departments got a brief reprieve from boarding during the COVID-19 pandemic, but most are seeing a return to prior volumes and, with it, the problem of boarding. While boarding is most acutely felt in emergency departments, the solutions to boarding are on the inpatient side, and they are not simple. They often require cultural and operational changes.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 07 – July 2021Improving the boarding burden is, in large part, predicated on bed capacity and efficient hospital-wide throughput. Decreasing the time patients spend in the emergency department after the decision has been made to admit does not just help us. Minimizing boarding is associated with a downstream positive effect on decreasing the entire inpatient length of stay (LOS).1,2 This is important when trying to align the inpatient and ED efforts. Moreover, delays in getting patients to inpatient beds have been associated with a variety of adverse events.3 Lengthy inpatient stays and discharge delays can lead to admission inefficiencies, resulting in a vicious cycle of delays in throughput.

Understanding Discharge Delays

Discharge delays occur when hospitalized patients remain in an inpatient bed beyond what is medically necessity. Discharge delays have negative consequences for both patients and hospitals. Just as the boarding of admitted patients in the emergency department is fraught with patient safety issues and suboptimal care delivery, discharge delays create comparable problems in the inpatient care continuum. With hospitals running at high occupancy, delayed discharges contribute to a host of negative conditions:4

- Delayed discharge is associated with increased mortality and infections and reductions in mobility and daily activities.5

- Delayed hospital discharges of older patients are common and associated with significant cost.6

However, addressing discharge delays is possible and can have benefits for the whole hospital system.

- New studies are helping to identify patients at risk for delayed discharges.7,8

- Discharge delays can often be remedied with care teams and managers.9

- Discharge timeliness has a positive impact on hospital crowding and ED flow.10

Boarding occurs due to demand-capacity mismatch, sometimes referred to as disequilibrium. Hospitals have staffed beds available for a finite number of patients, and they are occupied predominantly by ED patients, transfers into the facility, and procedural admissions. For most inpatient beds, there is already a new patient immediately ready for bed placement when the current occupant is discharged. Hospitals often operate under over-capacity conditions. When demand and capacity are so tightly matched, even the slightest delay in discharging a patient results in ED boarding.

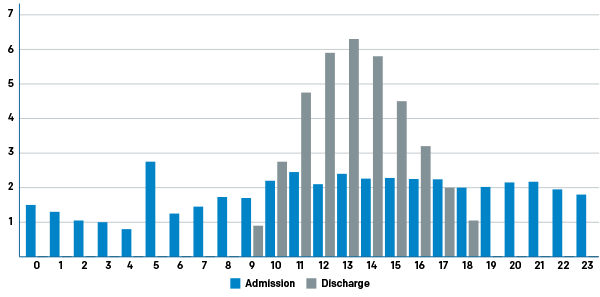

Figure 1 shows a typical admission and discharge disequilibrium curve during a 24-hour cycle. The red demonstrates admissions, which occur even after midnight from the emergency department. There are generally no discharges after midnight. The 5 a.m. admission spike is artifactual and represents data being populated with procedural admissions. The gray curve represents discharges or open beds by hour. Note that in this typical example, capacity for patients admitted after midnight does not match demand until after 2 p.m. This correlates to high arrival times for the emergency department, which is already in its own state of disequilibrium stemming from both from a high volume of arrivals and admitted patients not moving upstairs. In addition, a surge in discharges means a surge in “dirty beds,” which creates another mismatch: Environmental services/housekeeping typically scales back staffing at 3 p.m., just when emergency departments need them the most. This results in wasted inpatient bed capacity as rooms are empty but not clean.

Figure 1: Typical Hospital Disequilibrium by Hour of the Day

Shifting the discharge curve to the left has a number of positive effects. It creates capacity earlier in the day and smooths the workflow of the team.

Every inpatient bed falls prey to inefficiency due to suboptimally designed operations and processes. Patients no longer needing medical beds continue to occupy them due to process and system failures. Some of the contributors to this squandered capacity are:11–13

- Waiting for transportation

- Waiting for durable medical equipment

- Waiting for medications

- Waiting for a physician’s order to be written

- Waiting for the nurse to provide education

- Waiting for a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or rehabilitation facility bed placement

Hospitalists have become the busiest admitting service in most hospitals across the country, and beds for hospitalist service patients are often the tightest. Facilities that adhere to strict hospital geography by service often find themselves with even more difficulty placing admitted patients because an available bed may not belong to the service or the team to whom the patient has been admitted, creating yet another fixable barrier contributing to boarding.

Improving Discharge Rates

Though many hospitals have employed early discharge orders (eg, by 10 a.m.) as a performance metric for inpatient clinicians (particularly hospitalists), this typically does not translate into an empty clean bed for several hours. Many institutions are tracking true empty beds using a discharge by noon (DBN) metric, which better reflects efficient operations and processes around discharge. Inpatient care is a team sport, and a patient discharge requires a cast of characters touching the patient, including bedside nurses, physical therapists, pharmacists, and case managers. Achieving great DBN numbers requires strong teamwork.

Early discharges don’t happen without a concerted effort. To avoid readmission, patients need education, medication, durable medical equipment, follow-up appointments, and safe transportation home. Often a physical therapy evaluation is necessary to identify whether the patient is a fall risk at home.

All this planning requires coordination. Care coordination (also called case management) is a newer discipline, and care coordinators or case managers have become indispensable members of inpatient health care teams. These team members can be nurses or social workers. More mature departments have separated utilization review from case management and have identified more experienced workers to manage patients with complicated dispositions. Typically, it is harder to get patients going to SNFs or rehabilitation centers discharged early, though it varies by institution. Though it is not the whole story, many hospitals are focusing on the patients being discharged to home for the best results in DBN. That’s because the flow of these patients is the least dependent on factors that are out of the inpatient team’s control.

An evolving body of research describes strategies that can help increase DBN by addressing the barriers listed above. Strategies to increase early discharges include:

- Implementing discharge-focused rounds

- Scheduling discharges

- Using discharge whiteboards at patient bedside

- Using electronic discharge notification/communication/tracking

- Establishing a discharge or transition lounge (for more on this, see below)

- Having pharmacy students fill discharge prescriptions

- When safe, using ridesharing to transport patients home

- Reserving nursing home beds and homeless shelter beds for inpatients

Top-performing institutions implement a discharge rounding process that identifies tomorrow’s discharges today to allow the multidisciplinary team of nurses, case managers, physical therapists, pharmacists, and others to mobilize and organize their workflow to expedite the discharge and make sure it actually happens.14,15 Some institutions are now even scheduling discharges to further load-level the day.16 When an inpatient charge nurse knows who will be discharged, they can make nurse assignments accordingly so that one nurse does not have multiple patients to discharge. When physical and occupational therapists and case managers know who is being discharged, they can prioritize patients leaving that day. Even imaging and lab personnel can be organized to prioritize patients needing testing on the day of discharge. Highly efficient physicians will do much of the discharge paperwork the day before the anticipated discharge. These physicians also flip their personal workflow to discharge those patients first and then commence rounds on other inpatients. When everyone prioritizes getting patients home, capacity is created.

Good communication can facilitate early discharges. One surprisingly simple initiative that has shown improvement in early discharges is providing patient bedside whiteboards that notify and prepare them for discharge.17,18 At NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City, an email is sent with a discharge list to all stakeholders (physical therapy, occupational therapy, case management, nursing, imaging, lab, pharmacy) so they can organize their daily workflow to expedite these patients’ discharge process.19 EPIC has a discharge module that helps track patient milestones and discharges. TeleTracking is a patient software module that has a special discharge system with milestones for communication among the team. Ultimately, each hospital can harness technology to improve discharge communication.20

The discharge lounge (see photo) is a newer concept that has been implemented around the country to help get patients out of their beds, particularly when transportation home is delayed. They have had varying levels of success.21–23 A variation on this is the transition lounge. It remedies the problem of delays associated with interfacility transports, which often experience delays for patients waiting for basic or advanced life support–capable transport. In addition, receiving facilities have to communicate their willingness and ability to accept a patient. Valley Hospital Medical Center in Las Vegas created a transition lounge that could hold both patients going home who are awaiting their rides and patients going to SNFs or rehab centers. The hospital partnered with EMS to staff this lounge and parked a rig in the parking lot for the sole purpose of transporting these patients. Eventually, they evolved to a scheduled discharge and transport model.

Some regions have begun using ridesharing services like Uber and Lyft to transport patients who do not need a formal medical transport, with training to ensure that patients get into their homes safely.24

Another barrier to early discharge can be prescription provision, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. A promising approach includes using pharmacy interns or technicians to fill prescriptions for patients going home, with the process often beginning the night before.25 Finally, innovative health care systems like UCLA in Los Angeles are leasing SNF beds for their discharged patients, while Providence St. Peter Hospital in Olympia, Washington, is leasing shelter beds in the community for homeless patients being discharged.26

As emergency physicians who have been struggling with a nationwide boarding burden for almost 20 years, we are right to demand that our respective hospital leaders seriously address the issue using effective inpatient strategies for creating capacity. It won’t hurt if we understand the factors leading to discharge delays and bring a few ideas to the table.

References

- Krochmal P, Riley TA. Increased health care costs associated with ED overcrowding. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12(3):265-266.

- Derose SF, Gabayan GZ, Chiu VY, et al. Emergency department crowding predicts admission length-of-stay but not mortality in a large health system. Med Care. 2014;52(7):602-611.

- Sri-On J, Chang Y, Curley DP, et al. Boarding is associated with higher rates of medication delays and adverse events but fewer laboratory-related delays. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(9):1033-1036.

- Rojas-García A, Turner S, Pizzo E, et al. Impact and experiences of delayed discharge: a mixed-studies systematic review. Health Expect. 2018;21(1):41-56.

- Green MA, Dorfing D, Minton J, et al. Could the rise in mortality rates since 2015 be explained by changes in the number of delayed discharges of NHS patients? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(11):1068-1071.

- Landeiro F, Roberts K, Gray AM, et al. Delayed hospital discharges of older patients: a systematic review on prevalence and costs. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):e86-e97.

- Lenzi J, Mongardi M, Rucci P, et al. Sociodemographic, clinical and organisational factors associated with delayed hospital discharges: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:128.

- Feigal J, Park B, Bramante C, et al. Homelessness and discharge delays from an urban safety net hospital. Public Health. 2014;128(11):1033-1035.

- Aparecida da Silva A, Aparecido Valacio R, Carvalho Botelho F, et al. Reasons for discharge delays in teaching hospitals. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(2):314-321.

- Khanna S, Sier D, Boyle J, et al. Discharge timeliness and its impact on hospital crowding and emergency department flow performance. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(2):164-170.

- Mustafa A, Mahgoub S. Understanding and overcoming barriers to timely discharge from the pediatric units. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u209098.w3772.

- Hendy P, Patel JH, Kordbacheh T, et al. In-depth analysis of delays to patient discharge: a metropolitan teaching hospital experience. Clin Med (Lond). 2012;12(4):320-323.

- Okoniewska B, Santana MJ, Groshaus H, et al. Barriers to discharge in an acute care medical teaching unit: a qualitative analysis of health providers perceptions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:83-89.

- Patel H, Morduchowicz S, Mourand M. Using a systematic framework of interventions to improve early discharges. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(4):189-196.

- Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Iturrate E, et al. Discharge before noon: effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-669.

- Schedule the discharge to improve flow. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- Sehgal NL, Green A, Vidyarthi AR, et al. Patient whiteboards as a communication tool in the hospital setting: a survey of practices and recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(4):239-239.

- Tan M, Hooper Evans K, Braddock 3rd CH, et al. Patient whiteboards to improve patient-centred care in the hospital. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89(1056):604-609.

- Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214.

- Mehta RL, Baxendale B, Roth K, et al. Assessing the impact of the introduction of an electronic hospital discharge system on the completeness and timeliness of discharge communication: a before and after study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):624.

- Patient discharge lounge sparks connections, frees up beds. University of Rochester Medical Center website. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- Woods R, Sandoval R, Vermillion G, et al. The discharge lounge: a patient flow process solution. J Nurs Care Qual. 2020;35(3):240-244.

- Franklin BJ, Vakili S, Huckman RS, et al. The inpatient discharge lounge as a potential mechanism to mitigate emergency department boarding and crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(6):704-714.

- Donnelly L. Uber drivers to ferry elderly patients home from hospital in attempt to tackle record NHS bedblocking. The Telegraph website. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- Rogers J, Pal V, Merandi J, et al. Impact of a pharmacy student-driven medication delivery service at hospital discharge. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(5 Supplement 1):S24-S29.

- Bed leasing program helps hospitals discharge hard-to-place patients. Relias Media website. Accessed June 24, 2021.

No Responses to “Hospital-Wide Strategies for Reducing Inpatient Discharge Delays and Boarding”