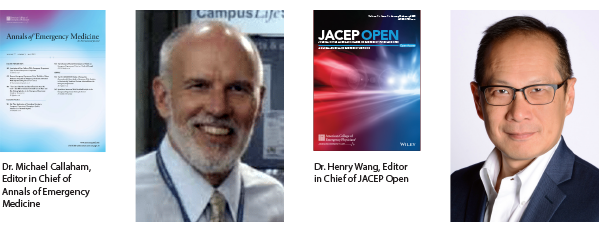

The need for expedient knowledge translation became apparent early in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians quickly found themselves in the midst of an “infodemic” as well—a torrent of misinformation and poor-quality information that was, at times, difficult to distinguish from trustworthy science. Peer-reviewed journals, which often take months to review and edit manuscripts prior to online “early view” publication, faced a record volume of submissions and intense pressure to publish quickly. Here, Michael Callaham, MD, Editor in Chief of Annals of Emergency Medicine, and Henry Wang, MD, MS, Editor in Chief of the Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, discuss the impact of these competing forces on the journals.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 05 – May 2021LW: The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have created a thirst for knowledge and a surge of manuscripts both preprint and peer-reviewed. How have you balanced the need for immediate knowledge with the desire for quality?

HW: We published the first issue of JACEP Open in early 2020, just as the pandemic was starting. We soon recognized that, given JACEP Open’s open-access format, we had an important opportunity—and obligation—to quickly disseminate information about COVID-19. We rallied our editorial resources to solicit and rapidly publish as many COVID-19 manuscripts as possible. We had to quickly add 10 new editors to our editorial board to ensure reasonable workloads and to maintain high-quality editorial oversight. Bear in mind that this surge of submissions occurred during the nascent phase of JACEP Open, a period where we expected to be striving to calibrate and achieve consistent editorial decisions.

LW: Has your view on the need or utility of preprints changed at all throughout the pandemic?

MC: I gained more experience with this than I’d had previously. One of my first papers to release as preprint was one of the few of quality [that we received]. I’ve concluded that the urgency or importance of the paper needs to be really solid to justify us preprinting something, and no one has solved the problem that quality review, revision, and selection take time and effort, often at a time when editors are overextended anyhow. Editors should remember that validity and quality are probably more important than novelty; the latter is worthless if the usual review process is bypassed. You’ll notice that even the biggest and most elite journals with the most resources made some astounding mistakes in their urge to be first out the gate.

LW: What about your views on open-access articles or the role of open-access journals during the pandemic—has this changed?

HW: Open access is an important publication model and potentially the scientific journal format of the future. Many of our customers delight in the fact that their accepted articles are accessible by anyone anywhere in the world. This is particularly important as we strive to connect with a diverse range of readers, many of whom do not have access to institutional subscriptions.

LW: Have you noticed any important changes or patterns in manuscripts?

MC: We have found the average quality of submissions on COVID is lower than our average. … Busy and overloaded clinicians and researchers respond to, “Quick, let’s find something to publish right now,” rather than, “This is complicated and needs a lot of expertise and evaluation—what a drag.”

LW: Do you think the ways in which clinicians are consuming articles have changed?

HW: Social media will continue to play an influential role in spreading the word about scientific papers. Today’s readers want information in as concise a format as possible. We need to continue reconceptualizing the format of the medical journals and articles so that they will be accessible to tomorrow’s readers.

MC: Probably, and that’s not a good thing. It is human nature to overlook the weaknesses of preprints in particular, even when you are aware of it and promise yourself you won’t succumb. The big journals have proven that wrong information can be promulgated, and clinicians have a hard time keeping in mind the separation between slow, thorough, high-quality peer review and the other kind. There is a reason that our peer-review process is the complex, slow test of veracity that it has been for some 200 years. What’s more important: to treat the patient fast or to give them the right and beneficial treatment? During COVID as well as normal times, our top priority is first do no harm. And that can seldom be assured with the first preliminary studies of a potential treatment.

Dr. Westafer (@LWestafer) is assistant professor of emergency medicine and emergency medicine research fellowship director at the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate and co-host of FOAMcast.

Dr. Westafer (@LWestafer) is assistant professor of emergency medicine and emergency medicine research fellowship director at the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate and co-host of FOAMcast.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “How COVID-19 Has Changed How Research Is Published and Consumed”